This Ancient Wonderland

The oldest part of a very old continent, with the oldest ecosystems, the oldest continuous human culture, and the ecological vitality of youth.

The oldest part of a very old continent…

The story of south-western Australia is almost as old as the earth itself. As the surface of the young molten earth began to cool into large plates of rock, huge slabs of ancient granite, formed.

One of these, the Yilgarn Craton, formed early and has floated on the surface of the earth for over 3 billion years. In that time it has formed parts of a number of supercontinents, as it bumped into and joined with younger pieces of rock and continental crust.

While most geological contemporaries of the Yilgarn Craton are gone – worn away over this immense period of time or drawn back into the earth – this enormous block of granite survived, and now stretches between the Pilbara and Stirling Range.

Calyerup Rocks

Image: Amanda Keesing

Granite at Gull Rock beach

Image: Amanda Keesing

We can still walk upon sections of this ancient crust – at Reynolds Hill or Calyerup Rocks near Jerramungup, or Yeedabirrup Rock near Kojonup, for instance. Imagine the changes that have taken place since those rocks were created – the evolution of life itself, dinosaurs, rainforests, ice-ages, and the arrival of humans.

Along the Craton’s southern edge, south of the Stirling Range and stretching to the east, is an ancient collision zone, that still bears the younger folded and crushed rocks from where the Yilgarn Craton crashed into another piece, the remains of which is now thought to be part of Antarctica. Those hard granitic rocks on the beaches from Albany east? That’s them, as are the steep granites of the Porongurup Range.

They are collectively called the Albany Fraser Orogen.

A stable land…

The features of this ancient landscape are more a result of what hasn’t happened, rather than what has. Unlike most of the earth, Western Australia has not experienced significant volcanic or mountain building activity for over a billion years.

Nor have we had the massive glaciers that can cover whole continents, wiping the biological slate clean and interrupting evolutionary pathways. It has been at least 250 million years since any large glaciers covered Western Australia, unlike most of the northern hemisphere which was covered by glaciers as recently as 12,000 years ago.

This long stability and isolation makes our ecosystems fundamentally different.

Vegetation at Gull Rock National Park

Image: Amanda Keesing

Stirling Range from Chillinup Rd

Image: Tim Leary

The only major force on this landscape has been a gradual weathering by wind and water, over millennia, resulting in a landscape so flat that you can see for miles from the top of any hill. This slow weathering has also leached nearly all the nutrients out of the soils, which haven’t been replenished by any geological activity bringing fresh minerals from deep within the earth.

But the edges of south-western Australia haven’t been completely devoid of geological activity: the western side of the ancient Yilgarn craton broke apart from India 130 million years ago, and then 53 million years ago along the southern edge it finally separated from the large southern continent. This created areas of more complicated geology around our coastlines, as well as patches of slightly richer soil, and some minor mountain ranges. Most of those mountains have since been weathered away to leave only the hard granitic cores behind.

An Ancient Ecosystem…

Justin Jonson

Threshold Environmental

“This is an ancient landscape. The vegetation here has evolved over millennia. We’ve got very, very, very old plant communities here, which are unique to the planet.”

Sylvia Leighton

Farmer and Soil Scientist

“It’s taken decades to start seeing how intricate and amazing and complex this landscape is. There are so many unknown components to the way this landscape functions and its natural ecosystems and in my lifetime we’re not even going to get anywhere near understanding that functioning, but that makes the mystery of it exciting.”

Some of the oldest plants and animals on earth…

Such an ancient and stable landscape has allowed ecosystems to evolve uninterrupted for hundreds of millions of years – much longer than almost anywhere else on earth.

Across south-western Australia some non-flowering plants, such as mosses and liverworts, and some groups of animals have been evolving virtually uninterrupted for at least 250 million years.

Moss near Albany

Image: Amanda Keesing

Velvet Worm

Image: Dr Georg Mayer

Velvet worms are one example of these true survivors – they started life underwater over 500 million years ago, then moved up onto land about 400 million years ago when the first forests of conifers, palms and lycopodiums were establishing.

Velvet worms saw the dinosaurs come and go, and they can still be found in the Porongurup Range today, mostly unchanged – their ‘design’ was pretty much perfect right from the start.

Flowering plants began to appear in south-western Australia about 130 million years ago, and have been evolving here, uninterrupted, for longer than almost anywhere else on earth.

This has led to some of the most ancient lineages of flowering plants on earth, and some of the richest diversity.

Banksias are amongst the most ancient flowering species to be found in WA. We have them as both fossils and living plants – looking remarkably similar today to 60 million years ago.

Banksia laevigata

Image: Nathan McQuoid

Some of the Richest Diversity on Earth

This uninterrupted evolution on ancient, weathered and nutrient poor soils, together with some relatively minor climatic variation in southern WA, has created extraordinary levels of biodiversity.

One third of Australia’s flowering plants can be found here, with many yet to be scientifically described. It is a botanist’s paradise.

You would think that less nutrients in the soil might mean less diversity of plants, but in fact the opposite is true.

Pitcher plants

Image: Paula Deegan

With ancient and infertile soils, plants and animals quickly evolved to fill all the available niches and developed a wide range of adaptations to survive – they found ingenious ways to access the limited water and nutrients available, as well as compete, cooperate, parasitise, hunt and protect themselves from others.

Carnivorous plants, symbiotic fungi, and wasps mating with orchid flowers are just a few fascinating examples.

Much of the geological diversity along the south coast comes from when the Yilgarn Craton and a much larger plate pushed against each other over 600 million years ago, pressuring and contorting rocks, and then uplifting them to form a series of mountain ranges, which are now largely gone.

But the geological mixing, and the many millennia that has since passed, has led to a diversity in soil types, which then contributes to the biological diversity.

Different plants have evolved different strategies to survive on these diverse and ancient soils, with some plants even engineering the soils as they scavenge nutrients from them.

Biological diversity at Caladenia Hill

Image: Amanda Keesing

Stirling Range

Image: Andrea Gaynor

There is also a significant long standing rainfall gradient across the south-west, from the wet forests in the west to the semi-arid conditions further east. Rainfall declines dramatically as you go inland, creating even more rapid changes in growing conditions.

You can drive through several completely different vegetation types in just a few hours, from lush karri forests near the south west coast to marri and jarrah forests further inland, then banksia heathlands and wandoo woodlands, right through to the mallee and woodlands that stretch off into the inland.

The Stirling Range, and the country around it, sits at the crossroads of many different geological formations, climatic zones, and vegetation types – creating some of the richest biodiversity in WA.

Plants and animals found no-where else on Earth…

Australia has now been isolated from other continents for over 140 million years. As a result, many of our plants and animals are endemic – they are not found anywhere else on earth.

South-western Australia, on top of its great geologic and evolutionary age, is surrounded by ocean, deserts and the Nullarbor Plain, and has been for millennia.

Mt Lindesay National Park

Image: Nicole Hodgson

Carnaby’s Cockatoo

Image: John Anderson

It’s effectively a biological island within the biological island of Australia, and has Australia’s biodiversity uniqueness on turbocharge. Almost half the plants here occur nowhere else in the world, along with many wildlife species, such as our three large cockatoos, our western ground parrots and western whipbirds.

Because of the sheer number of species, and endemic species here in the south-west, it has been designated one of the world’s top 36 biodiversity hotspots, where biological richness is highest, but also most threatened.

The oldest continuous human culture…

From a Noongar perspective, their ancestors were here in south-western Australia since the Nyittiny – the creation times.

In 2016 the WA parliament formally recognised that the Noongar people have been here ‘since time immemorial’. Western scientific methods have so far been able to provide evidence that Noongar people have lived in and maintained a profound cultural connection to south-western Australia for at least 45,000 years, and probably much longer. This makes Noongar people part of the longest continuing culture on earth – the First Nations people of Australia.

Noongar people lived here as ice ages came and went, sea levels rose and fell, species and ecosystems evolved. They lived where there is now deep ocean, walked hilltops that are now islands in today’s ocean, and showed enormous resilience and innovation to develop ways of living with boodja (country, land) throughout those eras.

Boodja is thus central to Noongar lore, culture and identity. The different Noongar groups in the Great Southern and wider south west – Menang, Goreng, Wirlomin, Wudjari, Kaneang and Wiilman – have origin stories for the country in which they have lived for so long, and a wisdom about how to live here now.

Ezzard Flowers

Noongar Elder

“We respect boodja because boodja to us is our mother, mother earth. Her blood line and her strength, and what flowed through her sustained us as a people, a community, a society. Even though you don’t see infrastructure that rises like the Empire State Building or Sydney Harbour, our infrastructure is the bush. We take care of it, we protect it, we preserve it, because it does the same for us.”

“Noongar people not only survived European colonisation but we thrived as family groups and sought to assert our rights to our booja.”

[Kaartdijin Noongar]

European Arrival…

Impact on Noongar people

Europeans began visiting this part of the world, especially along the coast, for many years before a permanent settlement was established.

Albany was the first European settlement, notable for initially harmonious relationships between the colonisers and the Noongar people

Albany coastline

Image: Tim Leary

“Noongar often led explorers through the region, probably without any idea of the consequences. Our intimate knowledge of the land and its waterways and fresh water was invaluable to the British. Many original walking trails used by Minang Noongar eventually became roads”

[Kaartdijin Noongar]

Clearing in Kojonup district

Image: courtesy of Judy Mathwin

As the settlement expanded, and Europeans took over more Noongar land, tensions grew and violence erupted. British law was imposed, introducing punishments for many things that had always been a core part of Noongar culture and life, including living on and looking after country.

New diseases, like flu and smallpox, were brought by the Europeans, killing many Noongar people. Eventually, large areas of land were cleared for farming, and Noongar people were pushed out.

Eugene Eades

Goreng Elder

“And you can see the sadness in the landscape, sad to think that we can’t and haven’t been considered to be a caretaker for country way back then. It’s Noongar land. We must be given the opportunity to go back and reconnect with the land and stories of the land and learn them and hand them down to the younger generation. It’s quite simple.”

Impact on Boodja

The arrival of Europeans had dramatic impacts on boodja. The colonisers largely denied Noongar people the ability to live on and care for their country, so traditional burning practices stopped, as well as the seasonal harvest of food, and caring for important water sources.

Systems and cycles that had been functioning for tens of thousands of years were put out of balance.

Salinity affected farmland

Image: Keith Bradby

Carol Pettersen

Noongar Elder

“Not only was the bush being cleared but it was our sites that were being cleared and then also the access to those sites that was being denied through the clearing and because the fencing came in and private property took over.”

Paddock trees

Image: Nicole Hodgson

The introduction of European farming methods, with widespread clearing of vegetation and grazing of hard-hoofed animals, has transformed this ancient land.

After World War II there was a massive expansion of agriculture in Western Australia, with more land cleared for agriculture in 45 years than in the previous 130 years of colonisation.

Until this point, there were islands of farms in a sea of bush. The huge expansion of agriculture transformed the landscape, so that now there are isolated islands of bush in a sea of farms.

Eddy Wajon

Conservationist

“We had this fantastic biodiversity and in the last 40 years I have just seen it disappearing right under my eyes from a variety of things: road safety, farmers expanding, fire, drought, climate change.”

Bringing European farming systems to WA has, perhaps more than anywhere else in the world, been a matter of learning on the job – in a rush.

The ancient landforms and soils have thrown up a wide range of issues, from the salinity caused as clearing released hundreds of millions of years of accumulated salt from the soil to the rapid acidification of many sands.

Even the business of growing crops and pastures on leached yellow and white sands has been challenging.

The techniques of farming have evolved rapidly, but farmers have had difficulty staying financially viable and reducing the impact of their systems.

Cropping on Chillinup Rd

Image: Nicole Hodgson

Impacts of salinity

Image: Keith Bradby

Replacing deep-rooted native vegetation with annual crops and pasture has brought salty groundwater to the surface, creating widespread salinity problems.

Our sandy soil has proved liable to blow away, burying fences and smothering road verges, and turning waterways with once deep pools into rivers of sand.

The fertiliser used to grow anything on nutrient poor sandy soils, has leached into waterways, causing toxic algal blooms.

Many weeds have been introduced, invading and out-competing native plants, while introduced animals, such as rabbits, foxes and cats, have all had an enormous impact on the ecosystem, especially on the small mammals which were once widespread.

Australia as an island continent has worked well biologically.

South-western Australia, as an island within that island has worked

spectacularly well biologically.

Tiny little islands of bush surrounded by farms – not so well.

A New Way – Working With the Land…

There were always voices expressing concern at the way western agriculture was developed in south-western Australia. From the dispossessed Noongar people through to those amongst the early pioneers who saw the beauty and special nature of the country, the Boodja.

Many strands of knowledge and concern have come together into the next wave of change – to regenerate and sustain the land with its many values.

Nowanup Rangers working in the Fitz-Stirling area

Image: Amanda Keesing

Landcare planting

Image: Bruce Radys

One expression of this strengthening approach was the rise of the landcare movement in the early 1980s, accelerated as it was by rapidly increasing salinity and consecutive years of severe wind erosion. In a strong partnership between farmers, the broader community and key government agencies, significant repair work was commenced.

Cleared creeklines, salt affected and low-lying areas were planted with deep-rooted salt tolerant natives. Waterways were fenced off from stock to prevent further erosion, and nutrient applications were refined to reduce loss through runoff into the creeks. Different cropping methods were developed to prevent loss of topsoil and increase soil organic matter and nutrient storage. Large-scale coordinated efforts began to control feral animals such as rabbits and foxes.

Environmental repair soon moved beyond individual properties, to whole catchments, to neighbours working together and groups of Friends’ adopting and caring for their local habitat areas.

More recently, this concern has broadened to develop large-scale landscape conservation initiatives.

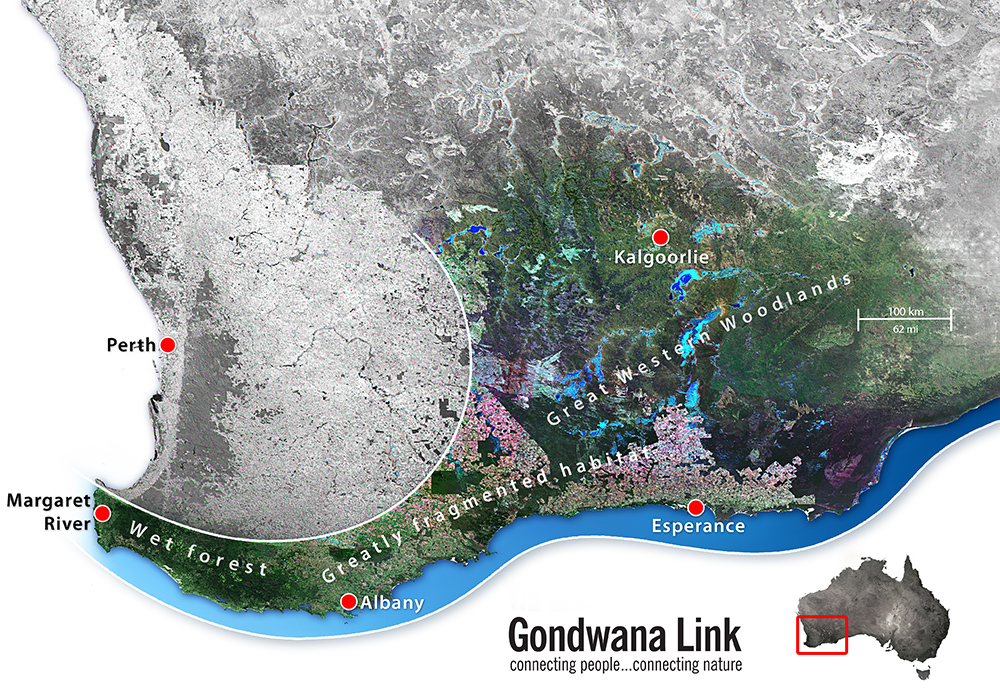

Gondwana Link is one of the early leaders, with its aim to reconnect and see ecologically focused management across a thousand kilometres of habitat in south western Australia.

It connects the efforts of many individual groups, ensuring that their work is contributing to a much bigger, cohesive landscape restoration achievement.

Nic Dunlop

Environmental Scientist

“What attracts me as a scientist to Gondwana Link is, it is actually the community-based approach to conservation, which is quite radically different to the approach taken by government or the role that industry might play in conservation. And hopefully it will establish a new kind of community, which is not just about conservation, but about people in landscapes and about not only making those landscapes function but maintaining an economic base, as well as the social connections and glue that allow communities to operate.”