Image: Frank Rijavec

A major environmental threat

Dryland salinity has been described as:

“one of the greatest environmental threats facing Western Australia’s agricultural land, water, biodiversity and infrastructure.” Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development

More than 1 million hectares of agricultural land in south-western Australia is severely affected by salt. Another 2.8 to 4.5 million hectares of low-lying or valley floor soils is under threat from salinization (DPIRD).

The drying climate as a result of climate change may have slowed the rate of salinity more recently, but saline watertables have continued to rise in many areas.

The impacts of salinity are significant: damage to soil structure, loss of productive farmland, waterways and wetlands, threats to native vegetation and ecosystems as well as impacting infrastructure.

Where did all the salt come from?

Like so much of our landscape history in south-western Australia, the story of salinity begins way back in our deep time history.

Parts of this landscape were under the sea during the Eocene period (some 45 million years ago) and when the water receded, salt was inevitably left behind.

On top of that salt already in the soil, add in millions of years of sea breezes which transported salt inland and deposited it on the soil. Rain dissolved the salt and washed it deeper into the soil profile.

In more arid parts of south-western Australia there are many naturally saline areas – places where there is not enough rainfall to leach salts from the soil and where evaporation is high. This results in a landscape of salt marshes, salt lakes, and salt flats. However even these naturally occurring saline areas are at risk from increased waterlogging and increased salinization.

Image: Nicole Hodgson

Deep salt is not the problem

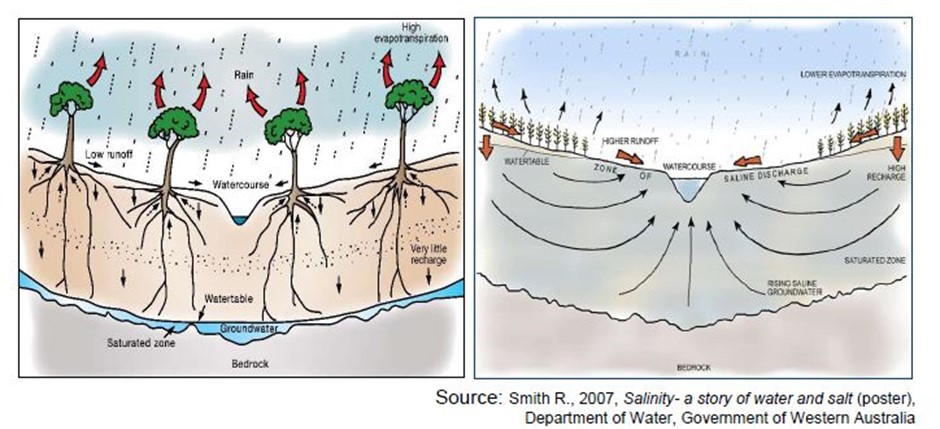

When the salt stays deep in the soil, it remains separate from the water table.

Native vegetation has evolved to be tolerant to the highly variable climate of south-western Australia and has deep roots to tap into the freshwater, so under native vegetation systems the salt stays buried deep in the soil.

European settlement and farming practices dramatically transformed the landscape of south-western Australia, removing the deep-rooted, perennial native vegetation and replacing it with shallow-rooted grasses and annual crops.

These introduced plants use far less groundwater. When the groundwater is not being utilised, the water table rises higher, bringing with it the salt that was previously buried deep in the soil. In the worst-affected areas, the water table and the salt may be brought to the surface.

Salt scalds and saline watercourses

It is often the flat or low-lying areas which are closest to the water table where the surface salt first becomes visible.

When the salt reaches the surface it changes everything – for the original vegetation, for waterways, for farmers, and for infrastructure. Almost every stream and river in south-western Australia is affected to some extent by salinity.

Species of plants that cannot tolerate the increased salinity and waterlogging will die, and only the most salt-tolerant and water-tolerant species remain. This changes the natural balance of the ecosystem and reduces the range of foods available for animals. In 2010, the then Department of Environment and Conservation estimated that 850 endemic flora and fauna species were at threat of extinction as a result of dryland salinity.

Image: Nicole Hodgson

Excess salt impacts not only natural ecosystems and farmland but built infrastructure as well. The full costs of salinity on roads, railways and buildings is not accurately known, but local governments estimate that salinity can halve the life of roads. Salinity in public water supply catchments has required huge investment in remediation or development of alternative supplies.

Heather Adams

Farmer and Chair, Oyster Harbour Catchment Group

When we arrived here in the 80s, I think the first very first thing that we did actually was we fence off a creek running through our property. We saw the benefits of doing that work just in the creeks so then we started to think ‘we’ve got a few salt areas, let’s get them sorted out’. So we fenced and planted salty areas.

That was probably what a lot of us did initially – we looked after degraded creeks and we fenced off and revegetated salt areas – they were sort of the couple of the key things everybody started to do in those early days of landcare.

Image: Keith Bradby

Addressing salinity

The impacts of European settlement and land management practices such as salinity, soil erosion and wind erosion, all became very evident in the late 1970s and 1980s, and in response the community landcare movement was born.

Revegetating salt-affected areas is a crucial way to get the deep-rooted native vegetation back into the landscape so that more of the groundwater is utilised. Eventually this helps to lower the water table, allowing the salt on the surface to be gradually leached deeper into the soil.

At a broader policy level, preventing any further clearing of native vegetation has been a major landscape-scale initiative to prevent salinity from worsening.

Find out more about what farmers are doing to manage dryland salinity in WA.

Heather Adams

Farmer and Chair, Oyster Harbour Catchment Group

When we arrived here in the 80s, I think the first very first thing that we did actually was we fence off a creek running through our property. We saw the benefits of doing that work just in the creeks so then we started to think ‘we’ve got a few salt areas, let’s get them sorted out’. So we fenced and planted salty areas.

That was probably what a lot of us did initially – we looked after degraded creeks and we fenced off and revegetated salt areas – they were sort of the couple of the key things everybody started to do in those early days of landcare.

Further Reading

Munns, R. and Passioura, J. ‘The dirt on our soils’. Australian Academy of Science. https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/dirt-our-soils

Beresford, Q., Bekle H., Phillips H. and Mulcock J (2001) The Salinity Crisis: Landscape, Communities and Politics. University of Western Australia Press, Crawley WA