Islands of habitat in south-western Australia

A theory of island biogeography

In 1967 the eminent ecologists WH Macarthur and EO Wilson published their seminal book ‘The Theory of Island Biogeography’. They set out with great clarity the basic principles of this theory – that the geographic size of islands determines the number of species they can hold over time.

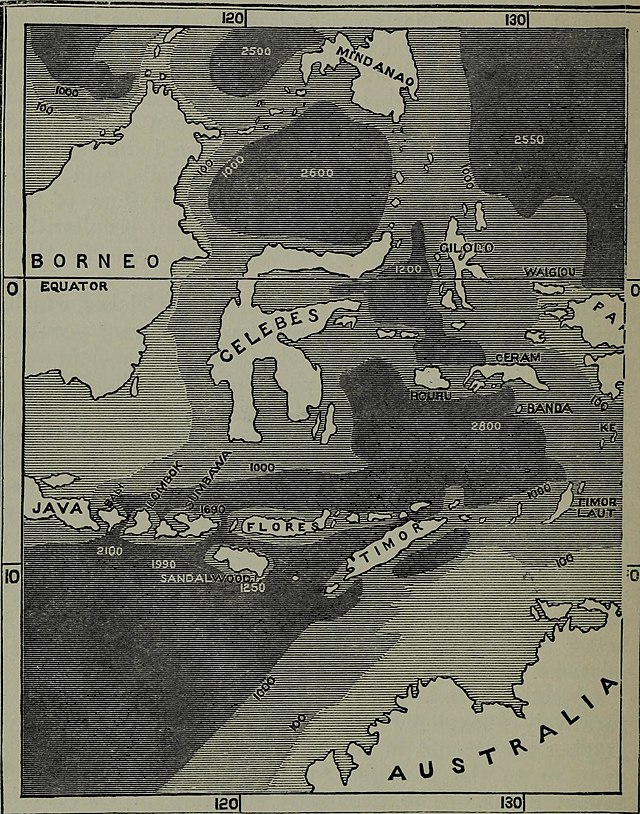

Their work built on centuries of ground-breaking science, back to the 19th century work of notables such as Charles Darwin, in the Galapagos, and Alfred Wallace, in the islands north of Australia.

Macarthur and Wilson took the principles that helped us understand our ecological past and applied them to our ecological future.

Alfred Wallace, Island Life

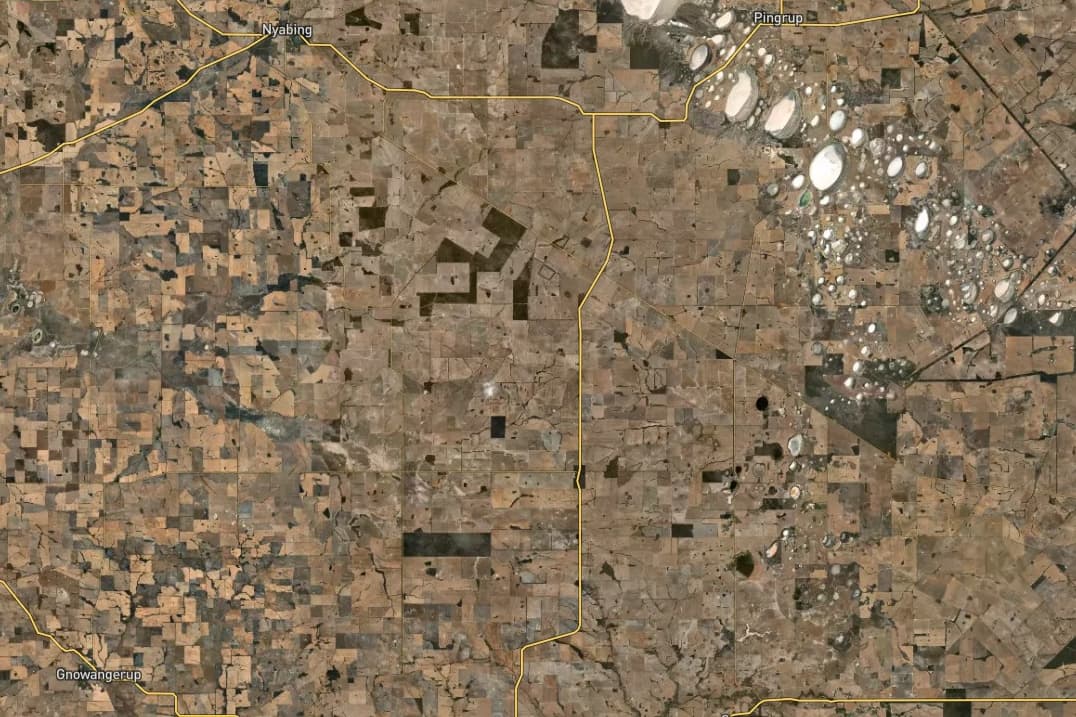

Wheatbelt islands of habitat

For the wheatbelt of south-western Australia, that could be a grim future. In 1980 and again in 1982 the WA Museum published analysis of the principles of island biogeography applied to the ‘islands’ of habitat left in a sea of modern agriculture.

Based on this analysis, the prognosis for the wheatbelt was not good – a prediction that bird species would halve in number and that only one nature reserve, Lake Magenta, was large enough to support its full complement of mammals.

That work, shocking as it is, still holds true, but was done before the full scale of climate change impacts was recognised.

Joining up islands

As no island of habitat does well in isolation, we need to stop regarding the isolated habitats we have left as ‘remnants’, the bits left-over, and see them as the strategic habitats we can build from.

That’s why our road reserves are so important, why landcare programs help farmers fence, protect and connect what bush they have left, and why nature reserve managers are reaching out to their neighbours. The great work in the last few decades done around wheatbelt reserves such as Dryandra and Dongolocking are good examples of this.

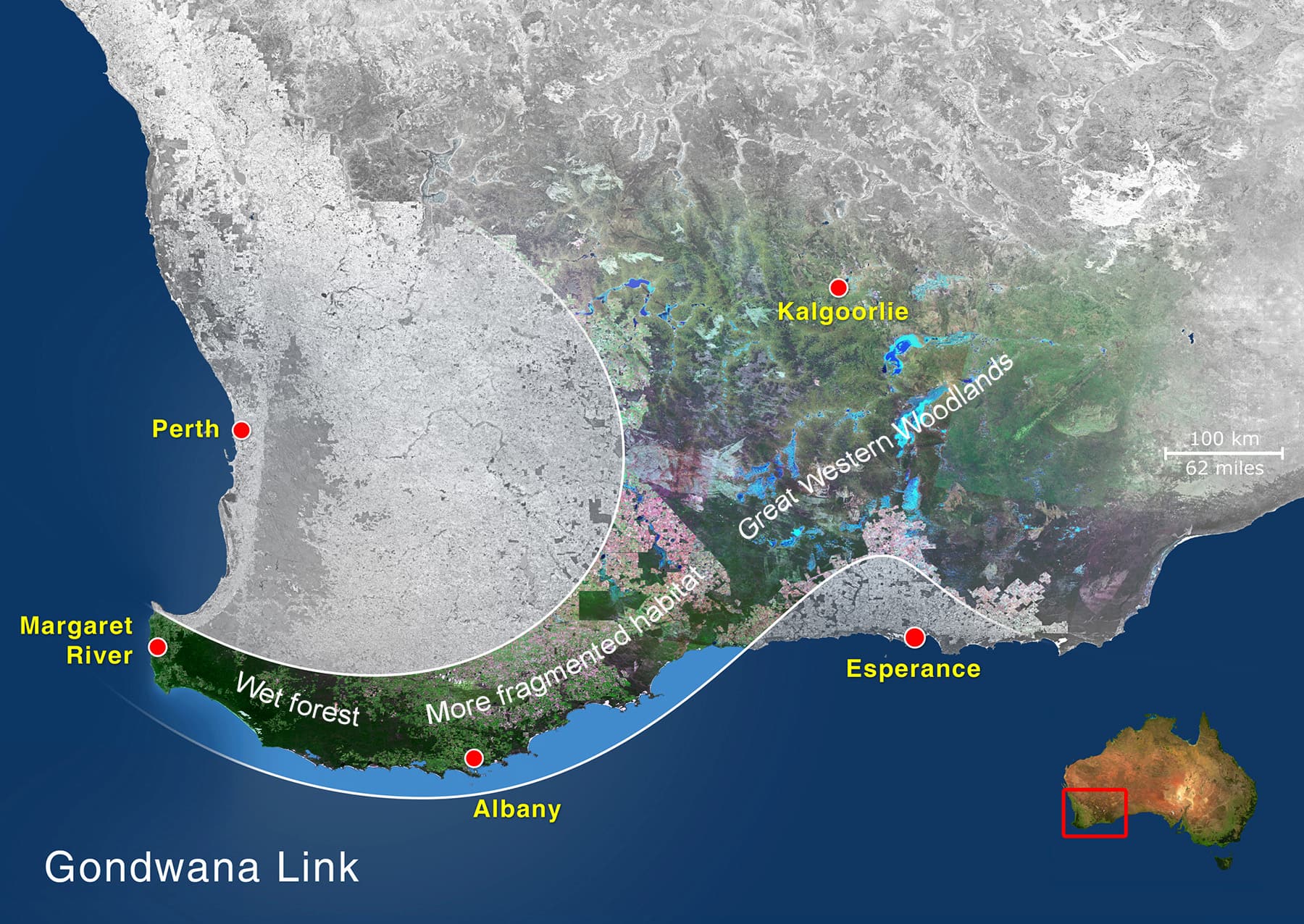

Implications for south-western Australia

The global theory of island biogeography has two key elements of particular importance in south-western Australia.

Firstly, our landscapes are made up of ‘soil islands’ formed through the great geological age of the area. These soil islands, with their own species and habitats have been isolated and re-united over aeons as the climate has fluctuated between wetter and dryer.

Secondly, Australian ecosystems work at large scales, in long term and unpredictable ‘boom and bust’ cycles that has historically forced many species to travel huge distances in nomadic cycles that are equally unpredictable.

That is why the scale of Gondwana Link is so important, and why even at 1000kms it may not be large enough for some species in a time of accelerated climate change.