Remarkable plants of the Great Southern

Incredible diversity

The Great Southern’s spectacular floral diversity isn’t just celebrated by scientists and conservationists. Nature lovers and tourists are drawn to the annual wildflower displays in late winter and spring, particularly in places like the Porongurup and Stirling Ranges and the sandier coastal and inland heathlands.

But while the peak flowering times are dramatic, at most times of the year there are treasures to be found – species that flower at different times of the year (the animals that rely on nectar and pollen need to be fed all year), amazing leaf forms, shapes and textures unlike those of any other place on earth, and the often cryptic animals associated with them.

Growing in the conditions that the southwest offers them, plants need to develop some impressive techniques for getting nutrition and water or to make sure their genetic material gets passed along. They’ve had a long time to develop their tricks. Here are a few examples of how some of them do it.

Image: Ami Vitale

Image: Paula Deegan

Albany Pitcher Plant

In peaty soils around swamps and stream edges along the southern coastal area west of Albany, lives the insect-eating Albany Pitcher Plant (Cephalotus follicularis), the sole species in the family Cephalotaceae.

This strange plant produces two types of leaves, one of which forms the pitchers, a few centimetres deep and part filled with a fluid that can digest insects, often ants.

The insects are attracted by nectar glands that grow on ribs on the outside of the pitcher, and crawl into the pitcher across a reddish-purple “mouth” which is smooth but has inward facing “teeth” that make it difficult for insects to crawl out again. There’s also a lid, which can close to preserve the digestive liquid in dry weather. The plants bear small white flowers in late summer.

It doesn’t appear to be related to other insectivorous plants, either in Australia or elsewhere, and the fact that it grows only in the wet habitats of the far south suggest it is a Gondwanan relict, literally clinging on at the edge.

Maintaining its habitats and particularly the wet conditions it needs (free of trampling by grazers or humans) are a conservation challenge, and one that will become more critical as climate change continues.

Image: Paula Deegan

Image: Nicole Hodgson

Kangaroo and Cat’s paws

Western Australia’s state floral emblem is the red and green Kangaroo Paw (Mangle’s Kangaroo Paw, Anigozanthus manglesii). There are 11 species and 13 subspecies of Anigozanthus, all of them endemic to the southwest of Western Australia and several of these grow in the Great Southern.

It’s their distinctive flower shape that gives them the common names of Kangaroo Paw or Catspaw, but the flower shapes actually owe more to some other fauna – the birds, principally Honeyeaters, that pollinate them.

The bright reds, orange and yellows of the flowers advertise the nectar to birds while the stalks provide a perch. As birds reach their beaks into the flowers to feed, pollen is deposited on the heads of the birds ready for transfer to the next flower as the birds make their rounds.

Differences in the flower sizes and shapes mean that the pollen is deposited on a different part of the birds’ heads, so that pollen from one species is unlikely to be deposited in another species’ flowers.

They tend to grow in sandy soils, often in winter wet areas like the margins of swamps or in some roadside swales. When massed groupings of them are in flower they make stunning displays (and these are reproduced each year in garden beds for the many visitors to Perth’s Kings Park Botanic Garden).

Image: Nicole Hodgson

Image: Jarrah Tree CC BY 2.0

Popular parasites

There’s a large group of parasitic plants around the world, and in this area, two of these are shrubs or small trees that are popular for different reasons.

Nyutsia Floribunda

The Christmas Tree Nuytsia floribunda is the world’s largest arborescent mistletoe. It’s not the fact that it’s a mistletoe that gives it its popular name; rather it’s the brilliant golden yellow to vibrant orange of its flowers that appear over summer, often in the weeks leading up to Christmas. It’s the Christmas tree that decorates itself.

The Christmas Tree has a clever solution to the low nutrient status of the sandy sites where it grows. Its roots have structures called haustoria, which cut into the roots of other plants and harvest nutrients and water. It is not totally dependent on its hosts, and it doesn’t kill them. In fact, it may parasitise many hosts from grasses to other trees, taking a small amount from each.

Its haustoria can extend at least 150m and they have been found on a wide range of hosts, as well as occasionally being found attached firmly to telephone cables and other underground structures.

Image: enjosmith CC BY 2.0

Image: Jean and Fred CC BY 2.0

Sandalwood

In a similar way, native sandalwood Santalum spicatum obtains its nitrogen by parasitising the roots of legumes such as Acacia species which are nitrogen-fixers.

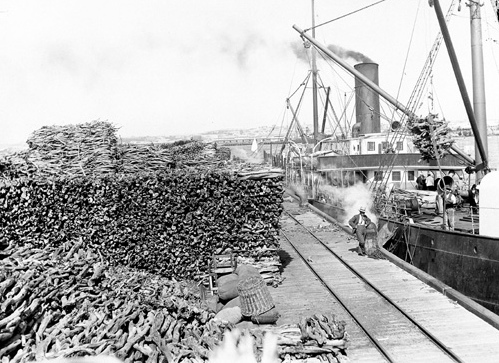

It has been well known as a source of aromatic oils since at least the mid nineteenth century when sandalwood ‘pullers’ (so called because the whole tree was pulled from the ground to access the oil-rich heartwood in the roots) began to harvest sandalwood from across its range.

To the north east of Albany, Sandalwood Road was so named because it was the route through for sandalwood being exported from a port established for the purpose at Cape Riche. The principal markets for sandalwood were China and Japan where the incense and joss sticks were widely used in religious ceremonies.

Sandalwood was widely harvested and gradually became hard to source. In recent decades native sandalwood has been established in plantings on farms across many parts of southwestern Australia.

Some of these plantings, for example at Peniup and Yarrabee private conservation reserves east of Albany, have included plantings of multiple host species so there is also a biodiversity benefit.

Sandalwood being loaded at Fremantle port, 1905

Image: Passey Collection

Further Reading