-

Toilets Available

-

Disabled Access

-

Picnic Areas

-

BBQ Available

-

Mobile Reception (Telstra)

-

Camping Allowed

Featured in journeys:

Take the scenic way to Albany

Overview

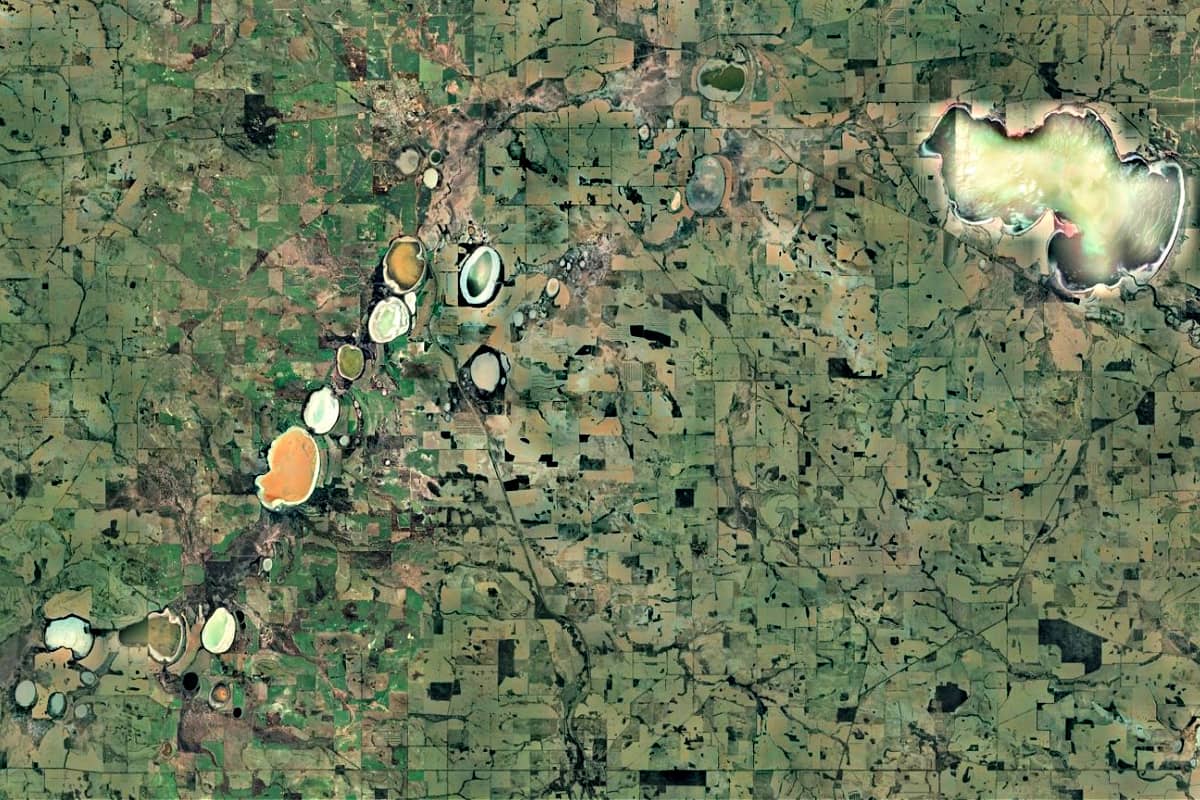

Lake Queerearrup is part of a long line of salt lakes running from Wagin in the north. The lake almost joins Lake Charling to the west and borders Flagstaff Lake on the east, hinting at the ancient history of this waterway, with this long chain of salt lakes the only remnant of an ancient paleo-drainage channel.

This remnant of an ancient river is now part of the Beaufort River Wetlands System North – a series of lakes, swamps and extensive floodplain along the broad floodway of the middle Beaufort River.

Queerearrup is the largest lake in the Shire of Woodanilling, at 430ha with a possible depth of up to 2 metres – when there is water in it.

Like many of the lakes in the Wheatbelt, this is an ephemeral lake that now rarely fills. Floods in 2017 filled the lake for the first time in about 30 years.

Now the lake is a popular camping spot, and a treasured recreation area for the surrounding community.

Story of the place

Noongar Boodja

This is the country of the Wiilman people of the Noongar Nation. The name of this lake comes from the Noongar ‘Queer’ meaning brush wallaby, otherwise known as black-gloved wallaby.

Other places in south-west WA have names the incorporate ‘Queer’ or ‘Kwor’, including as far away as Kwoorabup (Denmark River). This is one indication of just how widespread the brush wallaby or black-gloved wallaby was in the landscape.

There are stories of an important songline linking this chain of lakes. The nearby Wait-Jen walking trail near Wagin tells some of the Noongar history of this country.

Deep-time history

Lake Queerearrup is part of a distinct chain of lakes where the path of the ancient river can be clearly traced, especially in satellite imagery.

When this chain of lakes occasionally overflow they discharge water into the east branch of the Beaufort River.

All the major lakes in this chain were once fresh water. Around the 1960s / 1970s salinity in the lakes reached such high levels that they could no longer sustain the freshwater fish that had been previously introduced.

Gen Harvey

Wagin-Woody Landcare

“People just think that because it’s salty nothing lives there, but these salt lakes still have quite a diveristy of life in them. Especially after they’ve been inundated, because of all the dormancy, the seed that is designed to be dormant until a certain amount of rainfall. The vegetation communities that returned after the 2017 floods was just mind blowing.”

Beaufort River

Lake Queerearup is part of the Beaufort River catchment, one of the three main tributaries of the Arthur River, which in turn is a major source of the Blackwood River – the longest river in south-western Australia.

Historically, the water in the Beaufort River was fresh. The deep pools provided water for travellers and the pastoralists, and allowed for the grazing of stock and farming to begin in the area.

But, like most of the landscapes throughout the wheatbelt, extensive clearing in the catchment eventually increased the salinity.

From about the mid-1960s the Beaufort River became too saline to host freshwater fish that had been introduced to the system, as well as the native cobbler, marron and minnows. Increased salinity has unfortunately also impacted on the health of fringing vegetation and many trees bordering the river have died in the last few decades.

Settler History

Fertile land around Queerearrup and nearby Norring Lake was discovered early on, and so the land was grazed by pastoralists once the Perth to Albany road was built in the 1850s.

The first Europeans to settle next to the lake were the Cornwall family who built Queerearrup Station to the north of the lake and ran the property in conjunction with the Beaufort Station.

Thomas Cornwall was quoted as saying that no other land in the area apart from next to Queerearrup Lake and the Beaufort River would ever be taken up as it was too poor.

But eventually, when the railway line was established in the 1890s, more settlers began to come into the area.

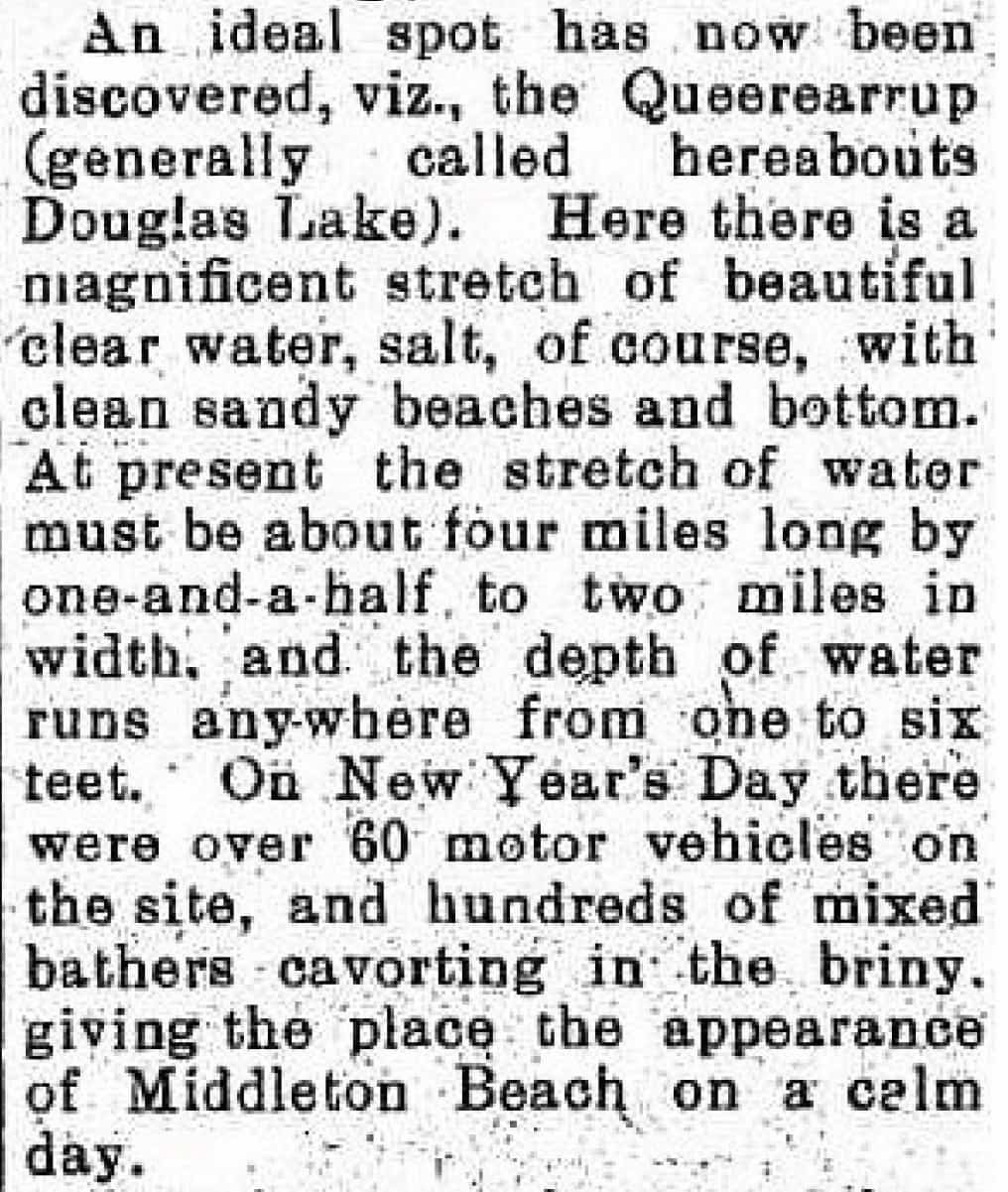

From the evidence of the regular reports of swimming and other water activities in the local newspapers Lake Queerearrup was a treasured recreation site for the local community, with picnics and celebrations regularly reported.

In 2018 the lake filled for the first time in decades, and the Woodanilling community responded with excitement, organising the Full Lake Frolic in late February – a continuation of the historical importance of Lake Queerearrup as a valued community recreation spot.

Southern Districts Advocate – 7 January 1929

See & Do

Camping and day use

Camping is available at Lake Queerearrup with new and well maintained public toilets, gas barbecues, and shelters available.

Plantlife

On the western side of the lake is a high bank with Melaleuca species closest to the water. Look out for the remains of dead trees closest to the water edge, an indication of increasing salinity and the decline of the less salt tolerant species. But there are also many seedlings and saplings growing up – those species that can cope with increased salinity.

Gen Harvey

Wagin-Woody Landcare

“The seedlings coming up are things like the paperbarks, the jam trees and York gums. Those species that are pretty tough and hardy, and survived the salinity originally. What’s missing is the biodiverse understorey, they’re often the plants that succumb to increased salinity.”

Tree species to look out for include:

Swamp sheoak (Casuarina obesa)

Image: Anne Rick

This species of casuarina is endemic to Western Australia and found from the Murchison River to east of Albany and inland to the goldfields and near Wiluna.

This tree is very tolerant of salt and water inundation, and so is a very important species for landcare plantings on salty and waterlogged land.

Jam (Acacia acuminata)

Image: Jean and Fred CC BY 2.0

Jam is endemic to the drier parts of south-western Australia, and is often found in conjunction with York gum, and sandalwood, where some remains.

Jam was very valuable for Noongar people. The gum was eaten to treat diarrohoea and aid digestion. The flowers were crushed and vapours inhaled to produce a good night’s sleep. Weak infusions of the flowers were used as washes for blisters and burns to aid healing. The gum was also mixed with water to make a drink called djilyan.

Swamp yate (Eucalyptus occidentalis)

Image: Anne Rick

‘Occidentalis’ means western, which refers to the occurrence of the swamp yate in the west of Australia. It is common in alkaline clay soils, often around wetlands and watercourses, and winter-wet depressions. It often forms dense stands with Melaleuca species.

Bird life

Woodanilling is known as a good area to spot birds, because of the mix of open country, nature reserves and lake / river systems. When there is water in the lake, a large number of waterbird species may be found here:

Other bird species you might see:

Giving back and getting involved

Wagin-Woodanilling Landcare Zone is the local landcare group for this area. Contact them to find out how you can get involved in landcare and environmental projects in their patch.

Nearby

There are many other sites to visit nearby including:

Practical Information

Directions

From Great Southern Highway travel along Robinson Rd for 17.5km. Turn left onto Reshke Rd. Turn left onto Douglas Rd and then follow the signs to Lake Queerearrup.

Nearby towns

Woodanilling – 26km away

Wagin – 29km away

Responsible tourism

When visiting Lake Queerearrup please make sure to Leave No Trace.

When to go

As with most places in south-western Australia, it is worth visiting during the wildflower season during Djilba and Kambarang (August to November) when most of the plants are flowering.

Where to eat and stay

See the suggestions from our friends at Great Southern Treasures: