A fascination with frogs

Emeritus Professor Dale Roberts has devoted much of his life to studying frogs in southern Western Australia. His interest in WA’s frogs started as a young university student in Adelaide. In 1978, after completing his doctorate in Zoology, this interest drew him across the Nullarbor. Forty-six years later, Dale now works from the Albany campus of the University of Western Australia’s (UWA) School of Biological Sciences. Dale’s story offers some of his rich knowledge and intriguing frog tales.

Let’s start with something that might surprise you. The south-western karri forest has a small area with the highest number of frog species per square kilometre in Australia ‒ comparable to some areas of the wet tropics in Queensland where we might expect a very high number of species. The Great Southern is not quite in that league. While we have plenty of frog species, many of them are cryptic, live in unexpected places or only appear after major rain events of 25 mm – an “inch”– or more. This article is about some of these species. It’s also about a career studying frogs in southern Western Australia and how that happened.

I went to university in Adelaide, confident I would be a marine biologist, studied Zoology and Genetics, dabbled in Psychology, and then focused on Zoology. In 1970, as an Honours student, I got my introduction to diversity in the Western Australian frog fauna when I had to write an essay on southern Australian biogeography (the geographic distribution of plants, animals and other life forms). I focused on one question: “Western Australia: why so many frog species and when did they evolve?”. That sparked my interest in frogs from south-western Australia, so in 1978 I moved to Perth and took a position at the University of Western Australia.

My first on-ground experience with Western Australia’s southern frog fauna was to drive along the Brookton Highway after a big autumn rain and see a hooting frog Heleioporus barycragus – a very large frog – sitting in the middle of the road. This was on the eastern edge of the jarrah-marri forest where it turned from forest to wheatbelt salt scar. The trees, the frog and the salt were all amazing sights for someone who grew up in South Australia.

South-west of a line from Shark Bay to Esperance there are about 27 named frog species. Just about everyone from Geraldton to Albany has seen and may have heard a motorbike frog, Litoria moorei: they’re big, and green and golden. Drive out on a wet night close to a wetland in spring or summer around Albany and you can be slip-sliding on hundreds of live and, many unfortunately dead, motorbike frogs. This species also commonly enters urban gardens. We frequently find adult frogs in our pond-free garden in Albany. Motorbike frogs are at the top end of the frog size-spectrum in Western Australia. They’re very mobile in the landscape but also very tough. They have been reported in a garden in Perth basking all day in the sun or dappled shade when shade temperatures were around 38°C or higher, which is very, very hot for a frog!

Its very close relative, the spotted-thighed frog Litoria cyclorhyncha, has been observed diving into hot, saline water. Both are very tough frogs that smash the stereotype of cute green frogs sitting on leaves in lily ponds! How they cope with high temperatures is unknown.

At the other end of the size spectrum, at about 1 cm long, is Nicholl’s toadlet, Metacrinia nichollsi. This frog never enters water. Its eggs are deposited on land, with one report of eggs, bizarrely, placed in a small bush above ground. Is that report fact or fiction? I trust the observer – he was my first doctoral student, Don Driscoll, now a Professor of Ecology at Deakin University. Nicholl’s toadlet has something like a tadpole stage, which occurs inside the egg, instead of in water. Fully formed small frogs then hatch from the eggs. The toadlet is superabundant all over Albany’s Mount Clarence: go out after rain in summer or early autumn and the mountain is literally alive with not hundreds, but thousands, of male frogs calling. This species occurs in the lower south-western forests from Augusta to Albany, in the Stirling Range and, maybe, in the Porongurup Range.

Are frogs that totally withdraw from water to breed rare? No. Just north of Perth, I studied the turtle frog, Myobatrachus gouldii, which breeds underground, not in water. Its common name reflects its similarity to a turtle with no shell. Its generic name Myobatrachus refers to its incredibly muscular chest (Myo – muscley, batrachus – frog), which reflects its habit of burrowing headfirst, whereas most burrowing frogs burrow backwards. These were the sort of bizarre frogs that fuelled my interest in working in WA.

Turtle frogs call after rain in November, which may seem like a rare event but the rain is usually associated with thunderstorms on hot days. This behaviour was discovered by a colleague Dr Alex Baynes, who was working on bats, at night, after a hot day with a thunderstorm and saw and heard turtle frogs calling. After hearing this from Alex, I was keen to head out to where he’d been working to follow-up his observation.

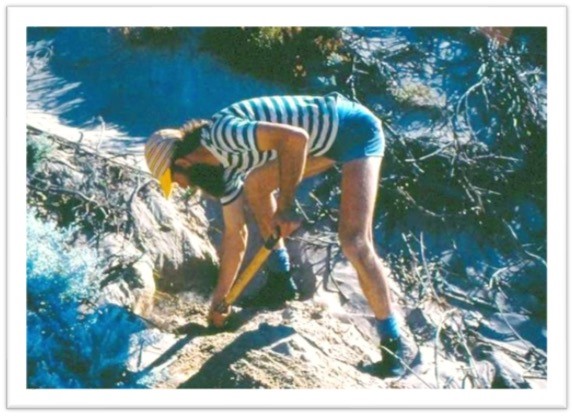

In November 1980, with a thunderstorm brewing, I called Alex for his opinion – he felt it was not hot enough and there was not enough rain, but out I went despite that pessimism. I found the area had been burnt to a crisp: literally black sticks, white sand and no leaf litter, but even so male frogs were calling all over. Females were approaching calling males, they met up, then burrowed forwards. I dug very deep holes, a metre plus, at several sites where I had seen males and females together and found frogs but no eggs. I put the frogs back and filled in the holes and tried again some weeks later in February. Jackpot: a clutch of eggs! Mystery solved. It was very clear why eggs of turtle frogs had never been found before: no one else had a thoughtful observer like Alex to inform them.

Turtle frogs also gave me one indelible memory. The late Professor AR (Bert) Main, from UWA’s Department of Zoology, had tried to unravel the breeding system of turtle frogs by looking at the seasonal pattern of egg development using museum specimens, but he got nowhere. Bert was tough but also a very fair person, yet on seeing the turtle frogs’ eggs, he was like a kid in a toy shop! Thrilled to the core to see a natural history “problem” at last solved. It was not deep science but a telling reminder of the immense value of natural history requiring careful observation of the natural world.

I have heard turtle frogs calling both north and south of the Stirling Range after rain in late spring, and this is almost certainly when they also call across the Great Southern. Turtle frogs can be very mobile. I have heard two reports of large numbers of this frog moving: one on the Chester Pass Road south of the Stirlings, another in the central wheatbelt. Both observations followed heavy rains in autumn, when it’s likely that pairs that had deposited eggs underground emerged to feed.

Is this breeding system unique? No. The sandhill frog, Arenophryne rotunda, found in sand dune systems from Shark Bay to Kalbarri, has an identical breeding pattern and, unsurprisingly, is closely related to the turtle frog.

If total withdrawal from water is one extreme of the breeding pattern in frogs, then burrowing frogs in the genus Neobatrachus are the other. Neobatrachus emerge after major rain events, prompting herpetologists like me to watch the weather closely. Long before the Internet, after I moved to Perth, I used to listen to the regional rainfall reports on the ABC Radio’s “Country Hour” every day. Twenty-five mm or more and a colleague or student and I were off: to the wheatbelt or, crazily, as far as Kalgoorlie and Menzies.

Frogs normally slough their skin regularly and often consume that skin: early adopters of recycling. Neobatrachus can form a completely waterproof cocoon from their sloughed skin, reduce their metabolic rate to maintenance levels thus conserving energy reserves, and sit underground for months or years at a time. Many years ago, I unwittingly left a Neobatrachus in some moist sand in a container. Two years, or so, later I opened the container and put the frog in water. It fought its way out of its cocoon and was perfectly healthy!

The Great Southern has three common Neobatrachus species: the wheatbelt frog, N. kunapalari; the humming frog, N. pelobatoides; and the white-footed frog, N. albipes. After heavy, widespread opening rains in autumn, I have stood in landscapes in the central and southern wheatbelt and heard literally thousands of Neobatrachus calling and breeding in temporary pools: a spectacular soundscape. Neobatrachus also breed after heavy rain from thunderstorms in summer.

With decades of experience behind me, I have a much better understanding of the answer to the question “Why does WA have so many frog species?”. The answer is time! We often think about the world as static, unchanging, but “molecular clocks”, used in 1967 to estimate the divergence of humans from other primates, have also been applied to Australian frogs. Many Australian frog lineages are very old – measured in millions of years not thousands. Over this timescale, there must have been many opportunities for frogs to evolve into different species (speciate) as variations in climate fragmented their populations.

In recent years, frog declines have been reported globally. The declines have commonly been attributed to “chytrid fungus”. Chytrid has decimated several frog species in eastern Australia, for example in Queensland’s wet tropics and around Mount Kosciuszko in southern NSW.

Based on samples from the quacking frog, Crinia georgiana, chytrid occurs right across south-western Australia, from Esperance to Perth at least. Some frog deaths in WA have been attributed to chytrid infections but there is no compelling pattern of chytrid-related population declines in the WA frog fauna. Why? Chytrid has had its biggest impact on frogs that spend extended time in water, for example species living and breeding in permanent streams or ponds. This covers many tree frog species in eastern Australia, as well as species breeding in permanently wet bogs, including the very impressive looking black and yellow corroboree frogs, Pseudophryne corroboree, in the Kosciuszko high country (with the additional threat of brumby populations destroying sphagnum bogs, where these frogs occur). In contrast, no frog species in south-western Australia lives permanently in streams, ponds or lakes.

Frogs in south-western Australia also get too hot in summer and too cold in winter for chytrid to survive. Is that true for the Great Southern? Yes, it’s very hot in summer ‒ I have heard of, near Elleker, and seen in Mount Barker, motorbike frogs sheltering from summer heat along roof rafters under a galvanised iron roof. Frost in winter, or worse? Yes, I stayed overnight in Narrogin last year and woke to a car covered in ice. Exposure to temperature extremes may be an important factor limiting the impact of chytrid in south-west Western Australia, but the absence of any frogs that preferentially breed in or spend extended time in streams or permanent water bodies is a very obvious difference from the behaviour of many declining or extinct frog species in eastern Australia and elsewhere across the globe.

My life chasing frogs in Western Australia has been exciting and fun! It has been a privilege to work through the far south-west, across the wheatbelt to the Goldfields, and in the Pilbara and the Kimberley. I have had some special experiences with frogs, other wildlife, and people. In a hired red Ford Falcon, a doctoral student from Sydney and I once drove 18 hours non-stop from Perth to Port Hedland chasing cyclonic rains. We found a veritable sea of frogs, and termites, covering the landscape.

Another thrill has been my part in scientifically describing and formally naming several frog species from southern Western Australia, including the glorious sunset frog found by colleague Professor Pierre Horwitz in 1994.

Equally important was a morning in 1982 with Dr Grant Wardell-Johnson, then a forester, after we had mapped the range of the Walpole frog – Geocrinia lutea (now in the genus Anstisia). Guided by “Forest Department” maps, we stopped at every creek crossing between the Deep and Frankland Rivers and from Walpole to the northern edge of the karri forest. We sat in the morning sunshine watching tiger snakes slither by. Our discussion speculated about whether other Anstisia species might occur in karri west of the Blackwood River. Answer: yes, the now very well known, white-bellied (A. alba) and orange-bellied (A. vittelina) frogs. Grant found both these species in 1983, the year after we had sat in the sun speculating.

Supervising 32 doctoral students and seeing their later individual successes has been a particularly satisfying aspect of my academic career ‒ I was especially proud when one of my students received UWA’s Robert Street Prize for the best doctoral thesis of his year: he worked on spiders not frogs!

I have some other legacies: the addition of call recordings of frogs to displays on Western Australian frogs at the WA Museum Boola Bardip (and on their website); the description of several new frog species in the Pilbara and the Kimberley; and as a member of the threatened species “Recovery Team” for the white-bellied and orange-bellied frogs. I have also made several broader contributions to frog conservation issues both nationally and globally.

I have never forgotten the early interest that was my start in science sparked by the then Curator of Marine Invertebrates at the South Australian Museum. I lived and grew up near the beach in Adelaide and often searched the beach after storms for prizes. There were plenty: like blue ringed octopus – they were fun to play with, but back then we didn’t know a bite could kill you; squid eggs in razor clam shells: when they hatched there were an awful lot of baby squid; and the egg case of a paper Nautilus – very cool. Then, when I was 13 going on 14, I found something we had never seen before: it looked like a hybrid of a snail. The front end looked snail-like and at the back end was squid tissue. Bizarre! It was identified by the then Curator of Marine Invertebrates at the SA Museum as a mollusc, with an invisible, internal shell.

In 1909, this species, now known as Philinopsis troubridgensis, had been dredged up on the Troubridge Shoal off Adelaide, but then never reported again, until I found one. Now it is illustrated and reported on in every skin-diving guide in South Australia. That experience and interaction were my invaluable start in real science.

I have no regrets about leaving marine biology behind, as there was another whole biological world out there: frogs that I knew nothing about, and I still can’t swim!

THANKS to Dale Roberts and photographers Greg Harold (also a herpetologist) and Holly Winkle. Editing by Gondwana Link’s Margaret Robertson and Keith Bradby, and Stephen Mattingley. This story has also been published in the June 2024 edition of the Southerly Magazine.

FURTHER INFORMATION

To listen to WA frog calls, via the WA Museum’s ‘Frog Calls’ web page, please scan the QR code. Scroll down to frogs of the south-west region.

More information on frogs, including distributions maps and call recordings, is available on the WA Museum website: https://museum.wa.gov.au/explore/frogwatch/frogs. Want to do more: explore the Frog ID app at the Australian Museum https://australian.museum/get-involved/citizen-science/frogid/