Art, poetry and their place in an ancient landscape

Bill Bunbury OAM speaks to Great Southern artist NIKKI GREEN and poet RENEÉ PETTITT-SCHIPP about their award-winning imagery and words and how they engage us with both the region’s ancient landscapes and natural beauty, and the challenge of managing human impacts. Their works also reflect respect for the land’s Noongar Custodians. They recently collaborated with Perth-based artist Monika Lukowska to present these and other works in the ‘Tracing Gondwana’ exhibition at the Midland Junction Arts Centre.

Bill: How can the arts connect with environmental concern and care for land?

Nikki: Without wanting to sound twee, art is connected to the heart. And I think that’s a primary concern when we’re caring for the land. So when I say heart, art and nature, all of that is about connecting to nature, building an appreciation for nature and wanting to care for it. Creative expression is something that has the power to touch. In terms of arts and environment, if you can touch someone, then you’re bringing them that much closer to connecting with nature.

Bill: Your journey here to the Great Southern and your obvious love for this region reminds me of the importance of a sense of place. How vital is that for human beings?

Nikki: Completely vital. I don’t know what happens if you don’t have a sense of place, but I would imagine that it would be like you’re on a boat in an ocean without a rudder, and you don’t really know which way to go. I think a sense of place gives your life a deeper meaning and informs your identity. A sense of place gives you purpose.

It’s not about ‘My foot is touching the earth and I feel this is where I need to be’. It is that connection with people, connection with the environment and connection with yourself and feeling part of a community. I am really aware that there are people who are sitting outside of that. And that would be really hard.

I guess that’s why it is an important thing in my life to embrace and include people and offer opportunity, especially to connect through the arts.

Bill: How have you offered inclusion and opportunity to people through the arts?

Nikki: As a practising artist and educator, passionate about community, I had worked in Melbourne on a school arts program which was inspired by an earlier visit to Denmark in WA and a meeting with Basil Schur of Green Skills. The program involved school kids looking at their local plants and animals with their arts, English and science teachers. That program showed me the power of getting young people engaged and learning through the arts. So when I moved to the Great Southern in 2007 and Basil introduced me to people working on the Gondwana Link, I just felt ‘Let’s try that here’.

So I did the Gondwana Youth Arts Project. It wasn’t just with visual art; we engaged artists of all kinds, like writers, dancers, musicians and filmmakers, to work with young people in the natural environment to show them what the environment can do to their creative flow. We ran some youth camps at Nowanup with a theme of ‘home’, getting the kids to make little burrows and imagine the idea of home out of natural materials. It was a fantastic opportunity to work with schools, professional artists, the environment, scientists and Noongar Elders.

I think that we absolutely need to listen to our First Nations people and their connection with country, their family and their own nations. We need to listen to the connection with the seasons. We need to listen to each other. We need to stop chasing financial gratification and look at receiving gratification through nature and family.

Bill: What does your collaboration with Reneé involve?

Nikki: As an artist, I don’t like to be locked into any one particular medium, but I love printmaking for its capacity to reach the wider public about social issues. Words and images can be intertwined. I like to work with text that is evocative and texts that might bring questions into people’s minds, make people wonder, invite curiosity. And Reneé’s words do that. Our combination of words and images explores the human impact on country.

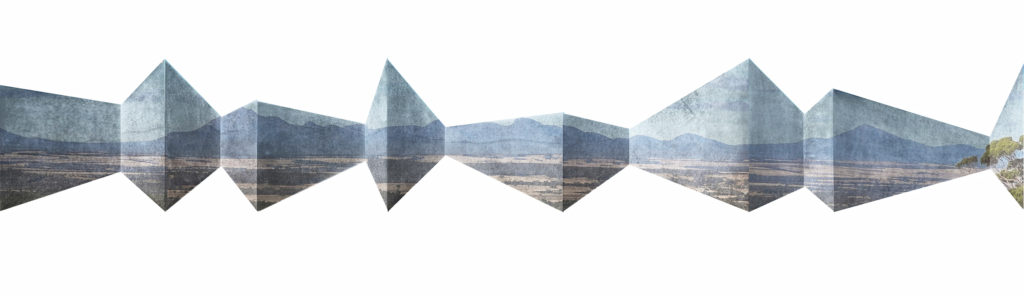

I have been working with another printmaker, Monika Lukowska, and I thought it would be meaningful to involve Reneé in a three-way conversation. This has resulted in the recently opened ‘Tracing Gondwana’ exhibition.

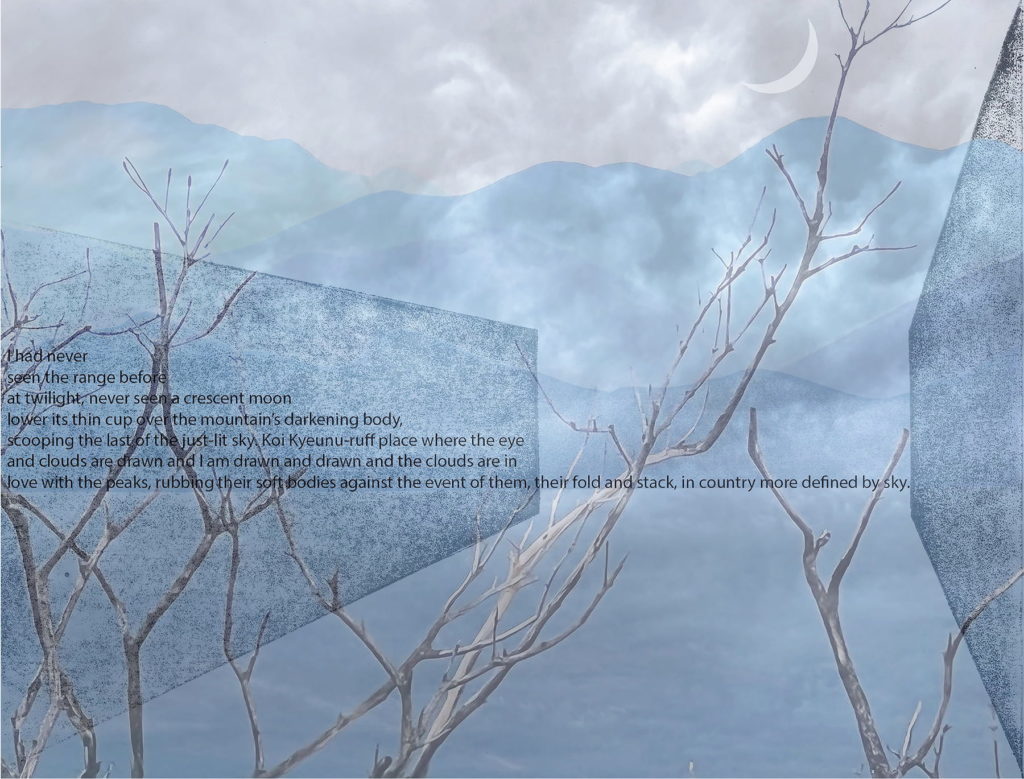

My work in the exhibition is largely based around Koi Kyeunu-ruff, which is the Noongar name for the Stirling Range. I have created a series of interpretations of the range which explores endemic flora, like the yellow mountain bell (Darwinia collina) and mountain banksia (Banksia montana) — precious wonders that are threatened by fire and dieback. Through my artwork, I have woven stanzas of Renee’s poetry that both inform and complement the underlying ecological message of the work. These interpretations feature concrete-like walls, inspired by brutalist architecture, to represent the human stamp on the natural environment. The walls, imposed on a seemingly incongruous natural landscape, form room-like spaces and within each of these rooms are a series of varying sized windows with views to the flora on the range.

Nowanup (extract) I had never seen the range before at twilight, never seen a crescent moon lower its thin cup over the mountain’s darkening body, scooping the last of the just-lit sky. Koi Kyeunu-ruff place where the eye and clouds are drawn and I am drawn and drawn and the clouds are in love with the peaks, rubbing their soft bodies against the event of them, their fold and stack, in country more defined by sky. Renée Pettitt-Schipp

My work for the ‘Tracing Gondwana’ exhibition started with a painting incorporating one of Reneé’s poems called ‘The Weeping Gums of No Tree Hill’. The whole background is filled with hundreds of lines of an ancient Hebrew invocation meaning ‘please, please heal her’. And it’s a real plea for healing. That’s healing country. That’s healing relationships. And in that respect, I think that we have to hold some hope. Because without hope, where are we?

Bill: Turning to you Reneé, what attracted you to Gondwana Link’s work?

Reneé: Hope! I would describe my work as bearing witness, and sometimes that’s an incredibly painful thing to have to do. So to come across something like Gondwana Link, which is so essentially hopeful, was wonderful. It’s hopeful not only because it’s physically regenerating sites that have been degraded, but it’s also forming links between sites, which then form links between communities. And, instead of being perpetrators, people can become part of the solution.

I became aware of Gondwana Link through my involvement in Nowanup. When I first came to Denmark, I was keen to make links with the Indigenous community. Nowanup was a really tangible way to do that, by going out there and seeing healing huts where stories are shared. But there’s also the land being healed and brought back from poor farmland to this incredible space of biodiversity.

In my life in Perth, I wasn’t able to form connections with Indigenous people because I did not know any Noongar people in my community. After meeting Uncle Eugene Eades and other Elders through Nowanup and hearing their stories, suddenly I could humanise the people in front of me. They were people like me. And I was so grateful to then feel a deep connection with the Elders who were sharing, and to begin to understand what had taken place on this very country.

The way in which the Indigenous Elders and people that I’ve worked with have not ‘othered’ me as a white person has been very inspiring, and a great example to really check that I do not ‘other’ others. Even if that person is someone who is clearing land, and I feel angry at them, they’re expressing their disconnection from the land and so I need to understand the humanity behind that. So I think for me, it’s been a real commitment to stay connected, even when it seems that you are disconnected from a person, and that person is different to you.

Bill: How does this disconnection between people and country affect them both?

Reneé: We’ve been taught to disconnect because places around us are being destroyed all the time. That’s traumatic. We see the natural world being destroyed, so we disconnect — we say ‘that’s not me’. But then we disconnect from what brings us deep joy as well.

A creek I drive by between Denmark and Albany was bulldozed. It was so painful for me because it was one of the places that I looked out for on my drive that filled me with hope. So it broke my heart to write a poem about what happened to this creek, but it restored something in me; it maintained my connection to the creek despite what had happened to it. So it becomes my form of resistance to disconnection.

I think that we have to connect to country to start developing the will to help it. So, when we start being in country and understanding country, then it becomes a part of us and not something separate from us. Then caring for it doesn’t become a ‘should’ but something we are inherently driven to do.

Legacy – a poem for my daughter (extract)

This morning the rain fell through the trees

like forgiveness

like everything could be undone;

days of drought had never come

the cat, the fox, the fire, the saw, the salt

as though reaching trees were left

to learn their leaves

the warbler to weave her nest

of webs and bark suspending her art

in air

Renée Pettitt-Schipp

Bill: Can poetry and visual art engage with each other?

Reneé: Yes. Often a poem for me will start with an image not with a word. Poems are my way of connecting. And often I just have this visual image of the words sewing me back into country — a personal healing in the work that I do, even when the work is difficult.

For me, the sharing between poetry and visual art is such a gift. To have your work in a book on a shelf is one thing, but then to be working with artists who bring it out from the shelf and into the world is a beautiful gift. So it’s been fascinating for me to see the way Nikki and Monika have been responding to my words with their artworks, bringing that visual element and the privilege of being deeply heard. It is a beautiful reciprocity.

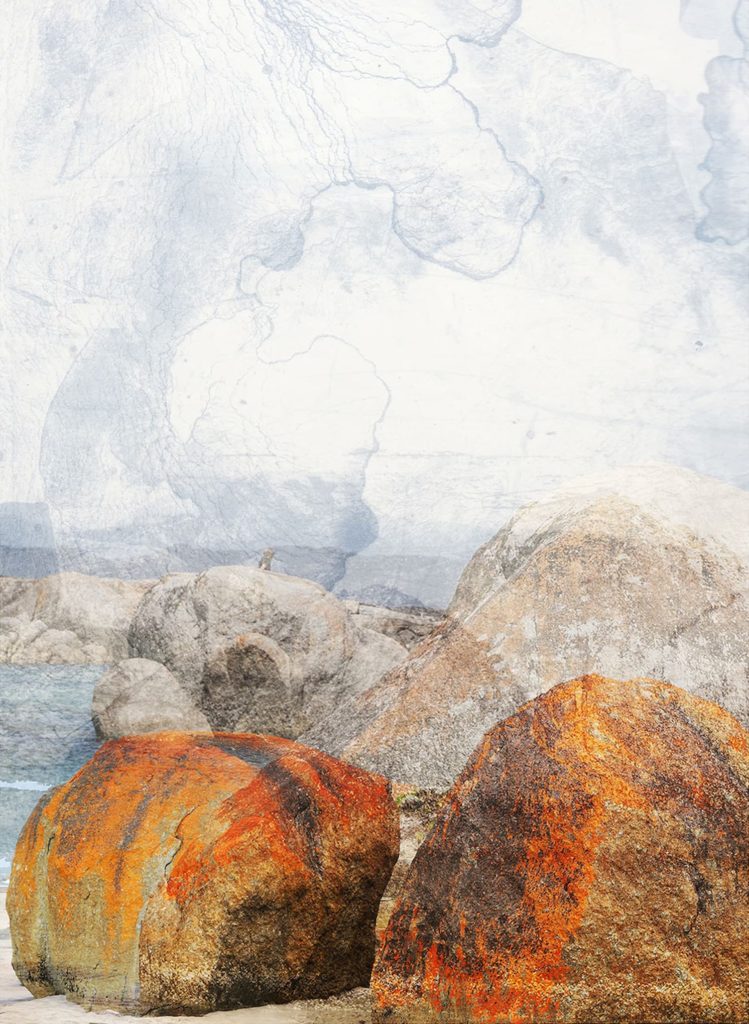

Elephant Rocks

To reach the beach we must pass through history

the pressure of it, billow of boulders high overhead

surge of Southern Ocean rising to knees

stealing in swift as a thief

we arrive, passage opening to sky

to stand stunned in Djeran’s crystalline light

towels still wedged under armpits, shoes held in our hands

from translucence the grand monoliths rise

each a narrative unearthed; violent acts

of upheaval and molten births

it makes our lives read differently, dwarfed

by geology we do not know but understand

white sand spilling perfection

out into the blue-green bay

where a herd of elephants ꟷ

feldspar and alkali, quartz and sanidine

make their slow way back out to sea.

Renée Pettitt-Schipp

Gondwana Link thanks Nikki Green, Reneé Pettitt-Schipp, Monika Lukowska, Bill and Jenny Bunbury and the photographers. Editing by Stephen Mattingley, Margaret Robertson and Keith Bradby; design by Carol Duncan.

The ‘Tracing Gondwana’ exhibition re-opens at the Midland Junction Arts Centre from 27 January to 18 February 2023, and will show at the Albany Town Hall in September 2023.

Further reading:

More about Nikki’s art practice: www.nikkigreen.com.au

More about Reneé’s poetry and writing: www.reneepettittschipp.com.au

The Power of Art in Landcare: Gondwana Connections Art Program (Giant Paintings Mapping Special Country) – a talk with PowerPoint slides presented by Green Skills’ Basil Schur to the National Landcare Conference 2022