Aunty Averil Dean: Rich rewards from family, culture and country

Aunty Averil Dean (née Williams) is a proud Cultural Elder with strong spiritual beliefs and connection to the land, especially the Stirling Range (Koi Kyeunu-ruff). Born in 1939 at Gnowangerup, Averil shares important insights about Noongar life in the communities of Gnowangerup, Tambellup, Cranbrook and Albany. In the late 1950s, Averil nursed in Broome, met her husband and started a family, before moving back to Tambellup. Here’s Averil’s story from the heart.

Aboriginal readers are warned that this story contains images of deceased persons.

I was born in the bush at the mission and lived there until I was about nine or 10. I discovered my Aboriginality by just being a kid with freedom to embrace the land, which was important to me because that was where my heart was; that was where my feelings were; and that was where I discovered a lot about my culture and myself.

As a Menang and Goreng Elder, I have a strong cultural connection to the land – it is part of my spirit, part of me. I have strong connection to my Dreaming and my cultural obligations, which include educating the wider community about the importance of Noongar heritage.

I had the privilege of being able to experience the spiritual strength of our old people who shared a strong connection to the land. Their spiritual strength shone through them with their relationship to nature and gave them the power to overcome adversity and go forward with pride in their cultural beliefs.

At the Gnowangerup Mission, Brother Wright discouraged the use of cultural practice and language because of Christian learning, and many Noongar people embraced that because it went alongside their own spiritual beliefs.

My Williams family didn’t speak much Noongar language to us as kids because they wanted us to learn the English way — they spoke a lot of words but they didn’t speak the language fluently in front of us. I think the biggest thing that we lost in our lives is the language because language is culture and culture is you.

Brother Wright, who formed and ran the mission, fought a lot of red tape and government policies to have the families live together, and he won that battle. He helped the Noongars make their own little houses and we lived together as families — we didn’t have that separation of being taken away.

I come from a really strong family and as a protected young child I experienced happiness in my home life and didn’t see the oppression that older family members were experiencing with the loss of their land and cultural practices.

When the Mission School was first built it was only a little shelter and the kids had to sit on kerosene tins. They only had school up to Year 3 and if the kids wanted to go on with education, they had to repeat. As the years progressed, when I came into school, the learning was more advanced but our schooling was pretty flexible and it was a happy place because we were all Noongar kids together and didn’t have to worry about whether we could fit in anywhere.

Gnowangerup was a very racist place, so the mission became like a safe haven. When Noongars went into town to shop, they had to wait outside until white people had finished their shopping. If they went into town, they had to be out by the six o’clock curfew or the police would come. Police were supposed to be the protectors but they were the instigators of a lot of violence and oppression that was shown against Noongar people. Our people lived by permits. For example, they had to get a permit to go outside the mission to work. At that time, Noongar kids weren’t accepted in state schools.

My grandfather always said he was a Menang person from Albany. He and his family, including my dad and brothers, my dad’s brothers and their sons, earned their living working long hours, with little pay, clearing the land, burning up, grubbing poison plants and fencing the farms. But it was Noongar land for goodness sake.

When the mission started to close down, our family moved to the Tambellup area, working on farms and camping in the bush. We went to school in Tambellup, catching a school bus. It was very different attending a white school as an Aboriginal child. You always felt you were being judged by what you wore and how you acted. At the school we suffered racial comments like ‘niggers’ and ‘boongs’.

At the school one day, I met two little kids and the boy said, “Oh, look, there’s a nigger now”. And I went up and slapped him — that was our only defence. No one wanted to listen to us. No one cared about what happened. He didn’t say it again.

But I made some great friends at Tambellup school – they are still my friends, my wonderful friends. You tend to grow above the racist comments when you meet people who have good hearts and you look for those sort of people in your life. At Tambellup school we started to get our learning together with the help of some teachers. I had a teacher who looked after me, so I was okay.

My dad said to us as children that this is no longer our land because these people have taken it over. He said that the only way that you can be successful and compete with them at their level is through education. For somebody who’d never had formal education, he was a very learned man. And he had this insight into what was the important thing for us in our lives — education. So we were never allowed to miss school.

The Welfare (Department) made regular checks on Aboriginal kids’ progress at school and singled out kids they felt would benefit from going away to school in Perth. The idea being to breed out the Aboriginality and teach them to live like white people and get rid of the bush culture that was part of their lives.

They focused on me and my brother in Tambellup school and asked my dad if we could go to school in Perth. He was adamant that “No, he wasn’t going to send his kids anywhere”. They persevered and in the end my dad relented, and he said, “Alright, I’ll let her go if you take her sister with her”, and so that’s how me and my sister Treasy went to Perth.

We stayed in Alvin House, a hostel, in Mount Lawley and went to Girdlestone High School. We wore a collar and tie and a beret and pleated skirt. Being dressed in full school uniform was, at first, a cultural shock. I think they hoped we would forget our Aboriginal culture.

One day my dad came up to the school — he came down to the back gate to attract our attention at the school lunch break. Treasy and I went down to him and he was dressed up in his old suit pants and his old coat and they were all clean and he was this Noongar and we were dressed up like white kids, you know. And I felt such a rush of love for this person. He was the most important person in my life — I felt such a rush of love. And I think that’s where my pride in who I was and who I will always be came to the fore. I was just so proud to be part of his life.

In the hostel, all the Aboriginal girls were taught how to adjust to life in white society — they made us polish floors and do other domestic chores. If the work was not done to their satisfaction, we had to redo it. Near the end of our school life, they put us in a factory to work while waiting to go into nursing aide training at Royal Perth Hospital.

After our training at Royal Perth, they offered the trainees a position in Broome Hospital because of short staffing. So me and my friend Verna took the plunge and said we would go. Two little Noongar girls on their first plane ride, not knowing anything about the local cultural protocol or the language, or how the people would react to us — it was scary.

After our arrival, on the first night, I had to go on duty by myself at the hospital. That scared the life out of me because I didn’t know enough then. Verna was more outgoing and soon made friends with Aboriginal staff who worked in the hospital. So we got to meet the wonderful Aboriginal people in Broome who welcomed us into their community as family. I met my husband, Kenneth Dean, and he became an important part of my life. We had three to four years in Broome and got married and had two children.

But I was missing family and feeling homesick, so we moved back to my country. We lived out on farming properties and he worked with my dad and family clearing land. He learned how to shear and became part of a powerful working family team.

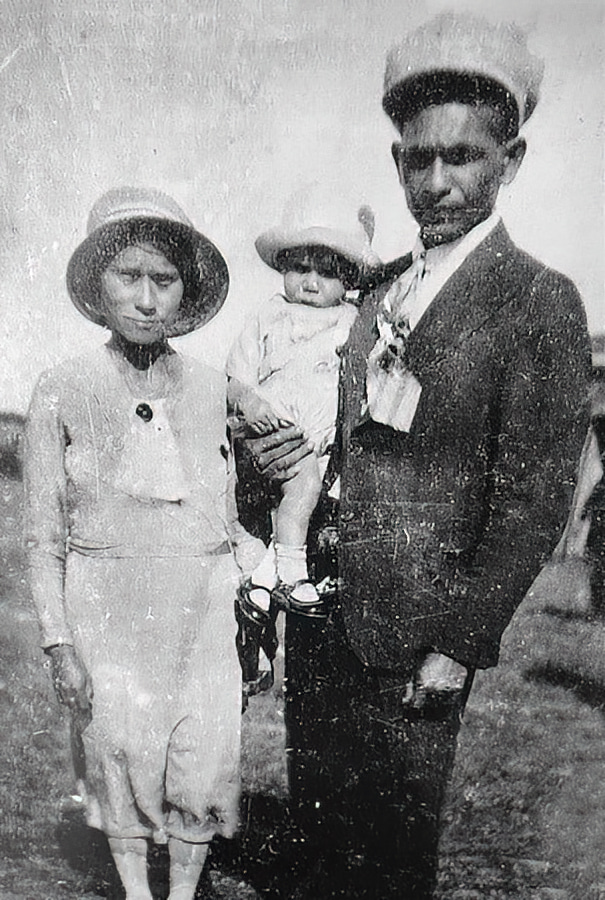

I pay tribute to my mum, Elsie Williams (née Hayward). She was a great lady. As kids, I guess we all tend to take our mums for granted, and don’t think about the impact they have in our lives. My mum worked incredibly hard, helping to clear the land and do the tasks that men do, and yet she still mothered us eleven kids. She would sit all day on a dam bank, washing clothes and boiling them in a kerosene bucket to keep the whites white. I didn’t realise, with admiration, the role that she played in our lives until I got a bit older.

In the late 60s, Kenny got a job in Cranbrook, so we moved our family and that became our home for 12 years. Because of his strong work ethics, he earned deep respect from the people of Cranbrook. It was like going to a different place because they accepted us and our children as part of the community. So life there was good.

The opportunity of a housing loan saw us move to Albany because we felt it would be beneficial to our children. We settled in Mount Lockyer and put our children in Mt Lockyer Primary School. Soon after, my brother Jack and his wife, Joan, also moved to Albany.

There was a teacher at Albany Senior High School, Will Richards, who was putting out feelers for Noongar speakers to do cultural studies with the Year 9s. So Jack and I started there in about 1972. We were joined shortly after by our sister Treasy. We used to go once a week. We took all the students on excursions to sites around the districts of Gnowangerup and Tambellup and Jack would talk about the significance of the sites and what they meant to us as Noongar people. I still work with the schools as a cultural teacher.

Many years after working in the high school, I went to Perth and I was in the Westpac bank in St. George’s Terrace, waiting to be served, when I was tapped on the shoulder. I looked around and there was this young white man. He had a suit on and a pink tie that stood out. He was a handsome young man. And he said to me “Oh, you’re Averil?” And I said, “Yes”. And he said, “You won’t know me, but I was in your class in Albany Senior High School and did your cultural learning”. “You know what” he said, “out of my whole school learning journey, yours was the best.”

That was my reward.

WARM THANKS to Aunty Averil and her family, including Sandra Brogden for assistance with photo captions; the photographers; and Bill Bunbury OAM for recording the original interview. Gondwana Link’s Marg Robertson, Keith Bradby and Carol Duncan assisted with the story’s development.

This story was first published in the May 2023 edition of the Southerly Magazine – with thanks to editor Wayne Harrington.

Further reading and listening:

The publication ‘NGULAK NGARNK NIDJA BOODJA: our mother, this land‘ (2000) includes rich oral history accounts by Averil Dean, Leonard (Jack) Williams and other Noongar Elders from the Great Southern and Wheatbelt. It’s published by the Centre for Indigenous History & the Arts.

‘A conversation with Jack Williams and Averil Dean: stories about country‘ is available here on Heartland Journeys. It’s drawn from a 2004 recording.

‘Boola Miyel: The place of many faces’ is a small book containing a story by Jack Williams and Averil Dean. Published in 2007 by Batchelor Press, the book comes with an audio recording of the story in Noongar language (ISBN-13: 978-1-74131-107-5).