Ezzard Flowers: Power drawn from his reconnection with country

EZZARD FLOWERS was taken from family at Gnowangerup at age eight and placed in Marribank mission in the Kojonup Shire. He was homesick and wanted family. Years later he faced the challenge of reconnecting to family and country. Now he’s a Noongar Elder and a widely respected community leader with many achievements to his name. In this story, Ezzard offers deeply moving and significant insights into family, culture, and country.

Aboriginal readers are warned that this story contains images of deceased persons.

“I was born in Gnowangerup, which is Goreng country. And I also have connection to Menang country and Wadjuri country. Before I was eight I was taken out on country — I learnt the language, I learnt the connections, I learnt the totems, I learnt the songs, and I actually knew what I was meant to be. But then at the age of eight, going on nine, that all came crumbling down because I was taken away from family.

“Those years leading up to me being sent away maintained their purpose for me in regard to my connection to country. That 1905 Aborigines Act was meant to break the spirit of the Aboriginal culture and the Aboriginal people, and to disempower us. But by putting us in missions in the bush, that sustained our sanity, simply because we had the bush there, we heard the birds, and we used to go for bushwalks every now and again. So we were still connected to country. But then there was the psychological impact of coming out the other side. We weren’t taught to be prepared for going back and looking for where we came from, knowing where our family was, and learning how to reconnect.

“When I was 14, I was moved from Marribank to Mogumber mission (formerly Moore River Native Settlement) north of Perth. I got homesick and when the mission brought us to the Perth Royal Show, I took off. And then from there was a life of running and hiding, doing silly things when you’re a youth, and I got caught and sent to a hostel in Kalgoorlie.

“From the age of 8 up until 18, I was basically trying to find myself and my way back home to Gnowangerup and family. Then at age 18, in 1975, I reconnected. It was all a big re-education process for me going back home, listening to my family and connecting to them again; sitting down listening and watching and hearing how they were talking, what they were doing.

“The process of reconnecting to family empowered me, but I was also going out on country with family, you know, taking the kangaroo dogs out hunting kangaroos or going down to Bremer fishing with family from Borden.

“In the previous family connections, I had all my grandmothers and grandfathers there. But this time, when I came out of the mission, they weren’t there, they had passed away. So all that I learnt from them prior to going into the mission, I had to try and pick up the bits and pieces.”

Education, including a Diploma in Aboriginal Mental Health, provided Ezzard with a vital pathway to reconnection and leadership. He is a 2015 joint recipient of the John Curtin Medal for his vision and leadership in the repatriation of Carrolup artworks to Australia. And he hasn’t stopped his passion for study: in February 2023, Ezzard will graduate with a Bachelor of Applied Science.

“It wasn’t until I was 35 that I realized that if I didn’t stop doing what I was doing, well then, I wouldn’t see 40. I was moving fast but going nowhere. That’s when I gave up my smoking, drinking and decided to go back and study.

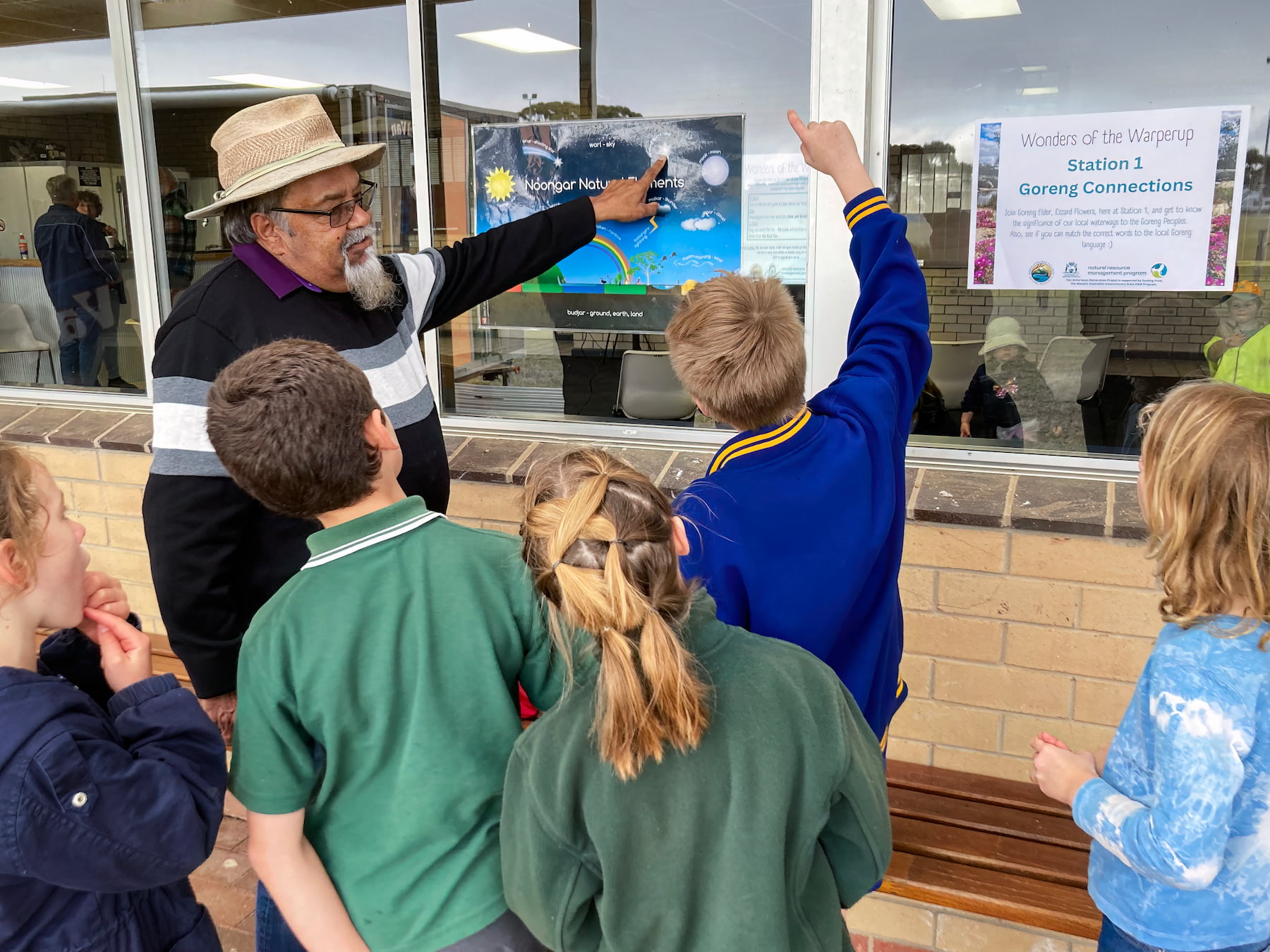

“Even though there’s been a void there for me, growing up from eight through to 35, I think going back into education has re-strengthened my spirit and reinvigorated my way of thinking systemically and culturally. Now, as I’m getting on in age, as a leader I don’t want to lead from the front, I want to lead from the side. I want to guide and pass on what I know to the next generation, so that my knowledge is not lost when I go.

“I want to make sure that people are working together, and when we come together, we all have a voice. And we all need to be mindful and respectful that what we bring to the table or on country should only be in support of one another and in collaboration with one another to look after what is important to us, not only as Aboriginal people or wadjela people, but as a human society.”

Ezzard has strong messages about caring for the environment, including a story that begins with young Ezzard and his family camping near five malleefowl nests in bush near Gnowangerup, before he was taken away to the mission.

“Prior to being sent away, there was everything there that I was able to connect to through my Elders — my uncles — especially when we were staying out at Mindarabin on a farm there, which is mallee country. Where we were camping in the bush, we had five huge malleefowl nests on our doorstep — the malleefowl were abundant back then. There was a single room house, asbestos with a brick chimney, that my grandmother and grandfather used to stay in — my grandfather was clearing the land for the local farmer there.

“Ever since coming out of the mission, I’ve been going back to that place where we’d been staying. That is an emotional reconnection, not only to see the clearing of the land and the malleefowl no longer there, but being back there brings to me how significant Aboriginal sustainability is for taking care of the environment.

“Aboriginal people need to be front and centre in all conversations, in all programmes, in all projects of sustainability. They can lead and guide and educate. People will then get a full understanding of the significance of why we are still here — because we haven’t rolled over and laid down. We still maintain our connection, our identity more so, simply because of the environment. And as long as the environment is still there, the boodja, the country, Aboriginal people will be still connected to that.

“Aboriginal people have got six seasons and they work to protect and preserve the environment through those six seasons. Everybody within the individual regions do their own protective taking care of country.

“Working with caring for country and looking after sites and listening to the Elders talk about significant sites in the region, it brought back a lot of the Dreaming connections, and the stories that connect from the land to the sky. The songlines and the stories that we were fortunate enough to get back from Gerhardt Laves (an American linguist who was here in the early 1930s), not only empowered me and renewed my spirit, it gave me a vision to look through the eyes of a blackfella and understand and connect how important the environment is to us in regards to our survival, our continuity and our collaboration and partnerships.

“When we look back to how this land was prior to settlement, we got to look from the Dreaming to the land, from the land to the culture, from the culture to spirituality, and from spirituality to the people. Aboriginal people always knew that their environment was within a circle, and that everything within that circle was used for the purpose of survival and sustainability. The circle was complete and unique, so much so that when Aboriginal people went to protect and sustain what they had within their culture, it was all about connecting to the biodiversity through knowledge that’s been handed down, whether it was through dance performances, corroborees, or whether it was through language in song.

“Oral knowledge and connection has always been passed down through two systems: one is the woman’s business, the other is the men’s business. And that’s how Aboriginal culture preserved and sustained itself up until the coming of European people. Then once European people came in, they looked at the land and the environment through different eyes. The Aboriginal eyes were that everything was connected and was there for a purpose. Why? Because not only was it a form that sustained them as people, but because of their totemic connection and also their spiritual connection.

“So spirituality and totemic connection sustain the Noongar people. Why? Because everything we see around us is not only living and part of the environment and its connectivity, but to us, because it’s totemic, it’s a living existence, it connects with our spirit.”

“The blackfella needs to be back on the land, working with the wadjela bloke, because all that knowledge and information that we share with one another can only mean that the legacy that we leave for the next generations will be a lot better and healthier.

“Once we learn how to communicate, collaborate, and work in partnership, then the land will get its strength back because at the moment, everybody’s working in boxes — there’s the box over here doing stuff, there’s a box over there doing stuff. But if we open those boxes to make it into a circle, then we can hear Mother boodja breathe a sigh of relief because at the moment her veins are being polluted because of introduced species, climate change and other things. Our totemic connections are disappearing in one way or another.

“We need to breathe life back into the nostrils of mother boodja to make sure that her heart is pumping again and that blood is running through her veins.

“There’s ways and means that we could do things to protect our environment. Not only do all us Aboriginal people have a totem, which is the birth and cultural identity given to each person for their journey on country, we want to pass on things like that to the broader community as well. Every Shire has an emblem, but we want to give them something to connect to from a cultural perspective. A sense of, not only when Mokare shook hands with wadjelas in Albany, but more: we want to not only shake hands, we want to embrace and work together for the better of our environment. We’ve got a beautiful environment, right from Walpole through to Esperance.

“When we talk about boodja, we respect boodja, because boodja to us is our Mother Earth, and her bloodline and her strength and what flowed through her sustained us as a people, as a community, as a society. Even though you don’t see infrastructure that rises like the Empire State Building or Sydney Harbour Bridge, our infrastructure is the bush; we take care of it, we protect it, we preserve it, why? Because it does the same for us.

…

Gondwana Link extends a special thank you to Ezzard Flowers for the original interview and our recent dialogue. Our thanks also to Frank Rijavec and Marg Robertson for the original interview recording, and to Kim Scott, Julie Hayden, John Stanton, Mary Gimondo, Caroline House and the photographers for their valuable contributions. Our editing and production team: Marg Robertson, Nicole Hodgson, Keith Bradby, Carol Duncan and Teresa Ashton Graham.

This Heartland Journeys story was also published in the February 2023 edition of the Southerly Magazine. Our thanks to the Southerly editor, Wayne Harrington.

Further reading and listening:

Hear Ezzard’s audio story, featuring material from the same interview as the written story presented on this page.

Ezzard’s written story was also published in the February 2023 edition of the Southerly Magazine. Click here to find the online version (click on the February 2023 edition and use the arrow key to go to pages 20-23).

Website: Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories

Website: Badgebup Aboriginal Corporation

Website, including video interviews and photos: The Carrolup Story

Website: Berndt Museum at University of WA / Carrolup

Website: Carrolup artwork at John Curtin Gallery, Curtin University

Wikipedia: Marribank (formerly Carrolup Native Settlement)

Wikipedia: Moore River Native Settlement / Mogumber Native Mission

Film: “No Longer a Wandering Spirit: the story of Bessy Flowers” – Ezzard narrates this 18 minute film about his remarkable Menang Noongar ancestor Bessy Flowers, who in 1867 was sent away from Albany to Victoria, never to return.

Book available from 1 March 2023: “No Longer a Wandering Spirit: Family and kin reclaiming the memory of Minang woman Bessy Flowers”, by Sharon Huebner, Ezzard Flowers and Kim Scott (Foreword); ISBN: 9781760802226.