Habitat plantings bring the birds

The birds come back! That’s the great news from cleared land that’s been carefully re-planted for nature in the Great Southern. After years of surveying revegetation areas on multiple properties, citizen science researchers and volunteers have confirmed the value of careful ecological design for achieving world-class outcomes for biodiversity conservation. And they’ve had a lot of fun doing it.

Meet Dr Nic Dunlop, Coordinator of the Citizen Science for Ecological Monitoring program at the Conservation Council of Western Australia. For decades, Nic has used his scientific knowledge and commitment to community-based conservation to advance citizen science projects and produce new knowledge.

His work includes surveying and analysing habitat restoration in the Gondwana Link, including plantings located between the Fitzgerald River and Stirling Range National Parks ‒ an area known as the Fitz-Stirling.

Story by Dr Nic Dunlop

I’m an animal ecologist which is why I’m working in the Gondwana Link. I work across many animal groups, but birds are my favourite. For 14 years I have had the good fortune to co-ordinate bird surveys of ecological restoration sites in the Fitz-Stirling area.

The context in which ecological restoration is taking place in the Fitz-Stirling area is this. Although the area is renowned for its high plant species diversity, its poor-quality soils have been grossly over cleared, with a very high proportion of the native vegetation degraded or lost to agricultural activities. And that has had consequences for erosion and soil condition, it’s had consequences for salinity, it’s had consequences for biodiversity and it’s had consequences for water in the landscape and probably for rainfall too.

So what we’re trying to do now is imagine a landscape where some of the original functionality is restored by reconnecting isolated bush areas and biodiversity through ecological plantings. This will improve the resilience of native plant and animal populations (their ability to cope with disturbance like fire and drought), and enable farming to be more sustainable, such as through soil stability and the presence of more beneficial species.

Over the years, especially since about 2004, I have witnessed and welcomed a rapid evolution in approaches to ecological restoration. There was the early landcare approach starting in the 1980s, which was often tree-planting with a few non-local species. Over time local species became more popular. Then from about 2004 it progressed towards biodiverse plantings for habitat restoration purposes, with seeds of native plant species sown directly into the ground. And even that has greatly changed since about 2008, as practitioners learnt from experience and improved the restoration technology and techniques.

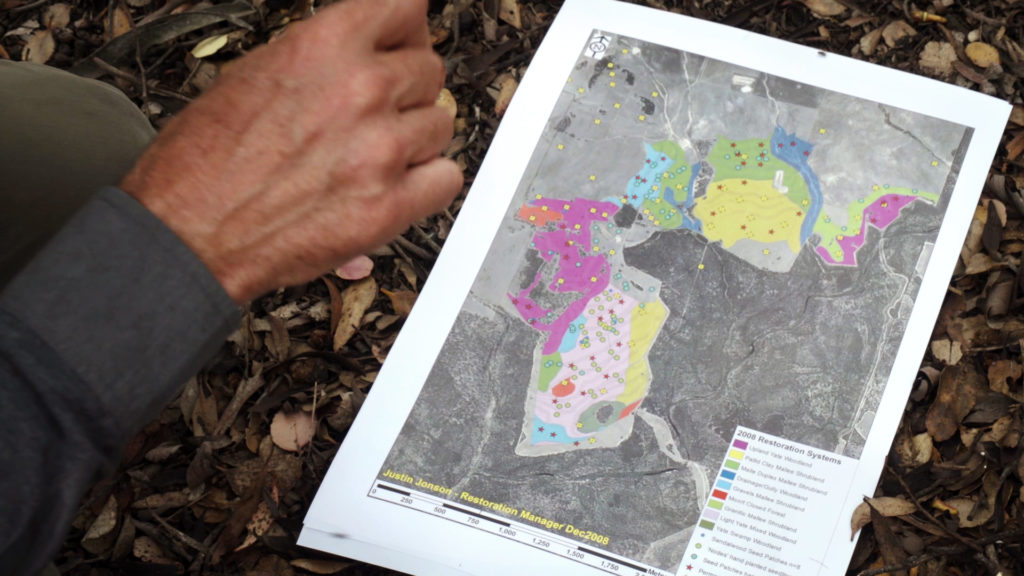

In the best of these more recent plantings, Justin Jonson has moved restoration practice from using a small number of native plant species, direct seeded in quite widely spaced rows, to systems with narrower row spacings, where over 100 plant species are used to achieve higher quality restoration.

He also matched seed mixes for soil types to greatly improve the chances of establishing vegetation and ecological processes ‒ things like nutrient cycling, pollination, seed dispersal and providing habitat for a whole range of animals. Restoration practitioners are getting away from just putting things in rows ‒ they’re trying to build in seeding and hand planting techniques that create a patchwork of irregular clumps and spaces to get a more natural, heterogeneous (diverse) type of plant cover.

So this modern restoration has much more diversity in terms of height structure (tree canopy, shrub mid-storey and understorey) and much more diversity in terms of horizontal structure, or patchiness (interspersed clumps and species), so it provides a lot more niches for different birds that occupy different habitats and use different resources. By using many more plant species you also get more arthropod diversity, such as insects and spiders. All those things are important components of habitat.

Here’s a key point. You can plant trees or establish vegetation and what you see as a result is self-evident, but what that’s not telling you is whether what you’ve done is actually leading to the restoration of ecological processes. To find out, you don’t look at the plants, you look at the animals, because it’s the animals that depend on those processes.

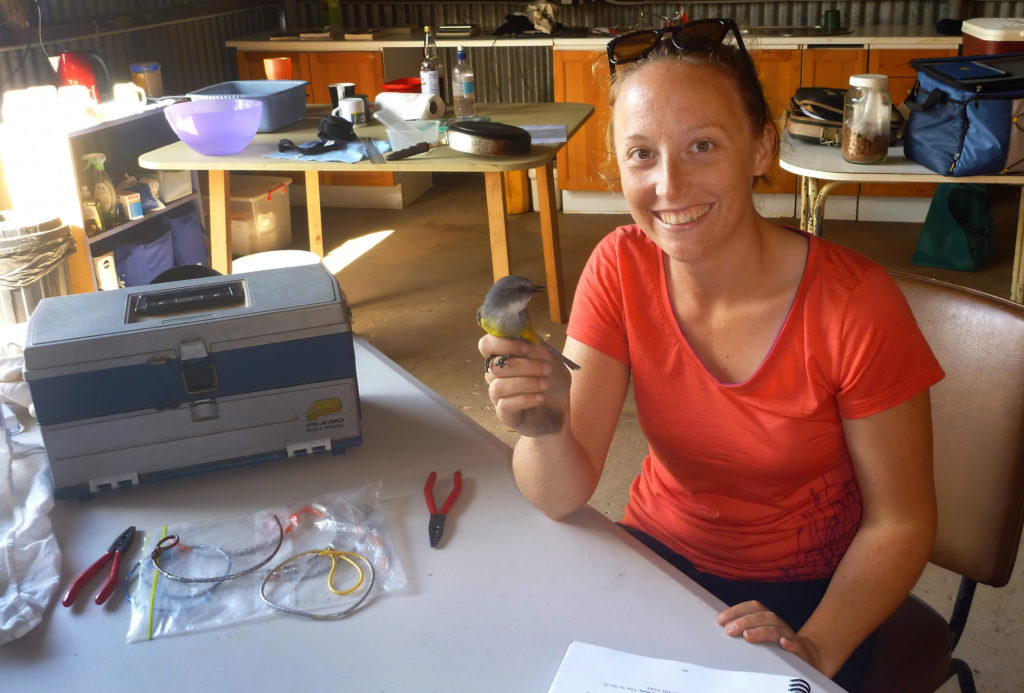

Then the next question is what animals could be sampled efficiently so we can determine how well the restoration is working? We could use almost any animal group, but in community-based conservation we have to do things that are going to be effective but also low cost. And one of the advantages of birds over mammals or reptiles or some invertebrate groups is that there are many more people ‒ volunteers ‒ who are capable of identifying birds than are capable of working with the other animal groups.

So we’ve evolved this process of using bird community and bird community structure as a basis for understanding the ecosystem processes developing in these restored ecosystems. Our pool of 99 regional bush-bird species has been divided into 13 functional groups based on the ecological resources these species require: whether they forage on the ground in dense heath, are aerial feeding insect eaters, or nomadic nectar feeders and so on. The occurrence of species from these functional groups is then used to assess the availability of these opportunities and resources over time in the restored areas.

Because they have the advantage of being able to fly, birds can also tell us about the condition of an isolated patch of vegetation better than something that can’t get there. A pygmy possum can’t travel many kilometres across open paddocks, whereas most birds have no real issues with colonising new places, if those places are suitable for them. So that’s another good reason for choosing them as an indicator of ecosystem change.

One of my great joys in life has been working with teams of passionate citizen scientists to collect bird data on ecosystem change. These citizen scientists receive training and mentoring from me and others so they can use the rigorous survey methods, and I then analyse the data.

In total we have conducted 14 years of investigation in the Fitz-Stirling area. During the last 5 years our focus has been the annual repeat sampling of a core group of sites. All this has been made possible by more than 100 bird observers contributing over 11,000 volunteer hours. They have all learnt there is no hiding in your tent at 4.30 am on a spring bird-monitoring trip!

In 2017 we did a snapshot survey of bird communities on various properties that had restoration treatments ranging in age from the earliest plantings back in 2004, right through to restoration that was done in 2014.

We expected to see a transition with the older and more established restoration having a more developed ecosystem, as indicated by the birds. But that’s not what we found. Some of the most recent restoration had got to a higher state of ecosystem development very quickly compared to older sites, some of which were now lagging well behind. So restoration that was done fourteen years prior had either not developed a whole lot of habitat and ecological process characteristics or had done so much more slowly.

Remarkably, the bird community structure tells us that in only five or six years the modern higher quality restoration planting can mimic our reference sites in the natural bush. It doesn’t LOOK particularly like remnant vegetation, but the evidence from our bird work is that functionally, as far as the birds are concerned, it is equivalent to undisturbed vegetation. By contrast, many of the early plantings had never got there over 14 or more years, and some of them may actually need more restoration work, because they’re not progressing. This is actually a very exciting result because it shows our ecological restoration techniques have improved greatly. This finding also has significance because if you’re seeing the development of ecosystem processes, then you’ll have a much higher chance that the ecological system you develop is actually going to persist in the long term, which is the outcome we’re after.

We’ve kept collecting the data every year since 2017 and I’m pleased to say it reinforces this finding.

Even with these encouraging results in the modern restoration sites, some fine-tuning is needed to provide opportunities for other animals to move in. For example, with early-stage restoration all the vegetation is young, so there’s very limited woody material like tree hollows and hollow logs or big piles of leaf litter which some animals need. Pygmy possums, for example, are probably quite important for eucalypt pollination, but they require small tree hollows for nesting in. We can speed up that process of having them resident in restoration areas by providing artificial hollows until the natural system develops them.

Insectivorous bats are also quite important in restoration, and the same encouragement can be provided by putting up bat boxes inside restoration to bring them in. These bats help with the early stages of restoration by regulating the numbers of insects. What we don’t want is plagues of grazing insects defoliating our vegetation and if some animal groups are missing then that’s more likely to occur.

It also turns out that some of the species which are not widely distributed and are regional endemics (found only in that area) absolutely love restoration, or at least modern restoration. The Western Whipbird is a classic example. The densities of whipbirds in restoration are probably on average higher than they are in the remnant vegetation. And that’s probably also true of some other birds like Scrub Robins and Babblers, which are also badly affected by fragmentation of bush in agricultural landscapes due to land clearing. So we’re quite surprised to see how quickly some of these significant bird species are using restoration areas.

One of the striking and quite amusing things about the more recent restoration is that Malleefowl love it. At the Monjebup and Chingarrup restoration sites in the Fitz-Stirling we are seeing Malleefowl mounds popping up with increasing frequency, and we encounter Malleefowl even when we’re quite a long distance from any remnant vegetation at Monjebup. So they are able to utilise these restored habitats and perhaps live entirely in them. That’s one of our regional threatened species that seems to be benefiting quite markedly from restoration.

Although restoration is not usually targeted at threatened animal species, it will also benefit them because it increases landscape resilience to disturbance such as fire or drought.

One of the critical things about the fragmented landscapes of the Fitz-Stirling ‒ and elsewhere ‒ is you’ve got limited areas left as remnant vegetation. So we need to ask what role is the restoration playing in animal populations in the broader landscape? It may already be providing extra habitat during critical periods where the climate conditions are not good, such as in a long drought. Because these systems are younger they have much faster growth, and are more productive than the actual bush itself. So there’s a lot more insects and other things available in this habitat than in the remnant vegetation. That means, for example, that a lot of birds might be able to maintain much higher populations now than they would have in the past, which ultimately improves the chances of those populations surviving in the broader landscape, particularly as climate change will put more and more pressure on those ecosystems.

Some of the more recent plantings are being funded through carbon offset funds. We need to be very cautious about forestry-style tree-planting projects that could have a negative impact on biodiversity and landscape function. But if carbon plantings are done well, with biodiversity conservation as a key outcome, they can make a modest contribution to slowing climate change and a big contribution to helping the local vegetation and wildlife cope with climate change.

THANKS to Dr Nic Dunlop, Alison Goundrey, the photographers, and Frank Rijavec for the original recording.

For further information:

A Heartland Journeys audio version of Nic’s story is available here

Restoration ecologist Justin Jonson talks about his work to refine the science of restoring habitats here

Bill Thompson writes about the inspiring ‘Yarraweyah Falls’ restoration project in the Fitz-Stirling here

There is much to enjoy and ponder in Eddy and Donna Wajon’s story about ‘Chingarrup Sanctuary’ and its revegetation, which can can be heard and read here