Katrina Syme: Delving into the fascinating world of fungi

For over forty years, Katrina Syme has collected, painted and documented fungi from across Australia, most extensively in forest and coastal environments around her hometown of Denmark. Back in 1982, a long family holiday to Tasmania sparked a symbiotic relationship between Katrina and fungi, and now she is one of WA’s foremost fungi aficionados and experts.

Albany multimedia producer Josephine Hayes talked with Katrina at her Denmark home and in the forest, documenting her extraordinary knowledge of native fungi. What a story!

A rainbow of lever arch files bloom from Katrina’s light-filled study. Each folder is dense with detailed scientific knowledge, diagrams and descriptions about fungi, as well as lichens, mosses and liverworts.

Near the window, a bristle of brushes stand patiently in a mug and cubes of watercolour are ready to engage with a carefully gathered mélange of seeds, leaves, fungi and twigs.

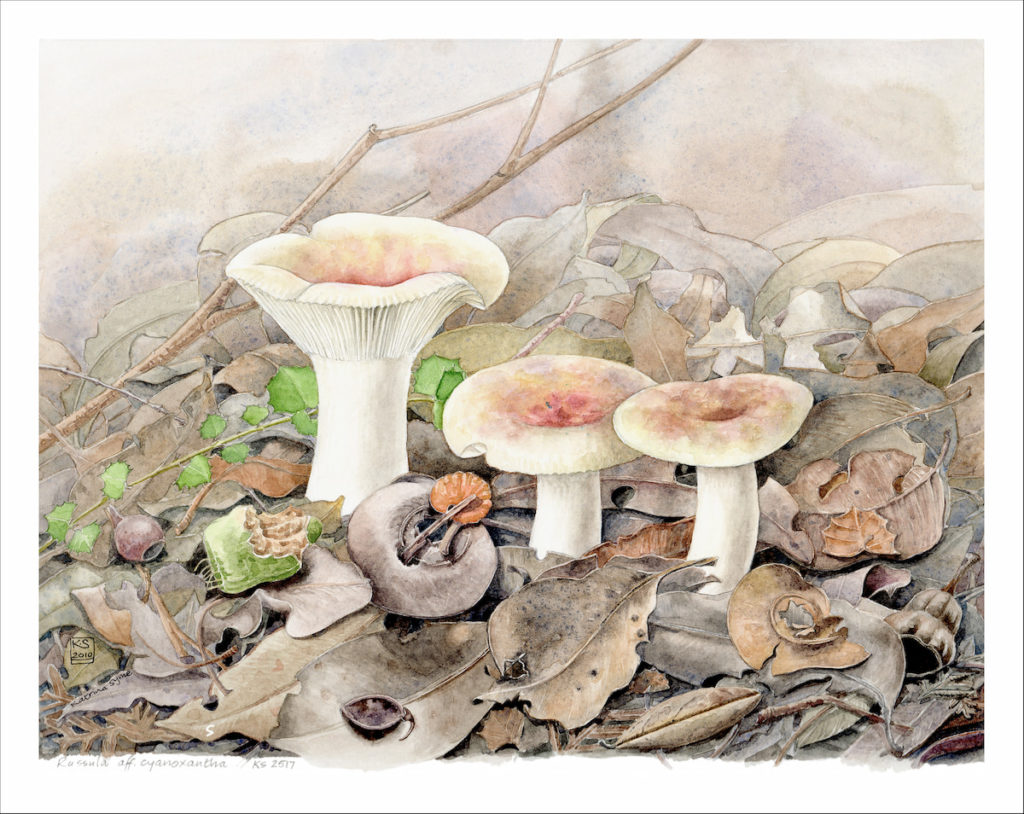

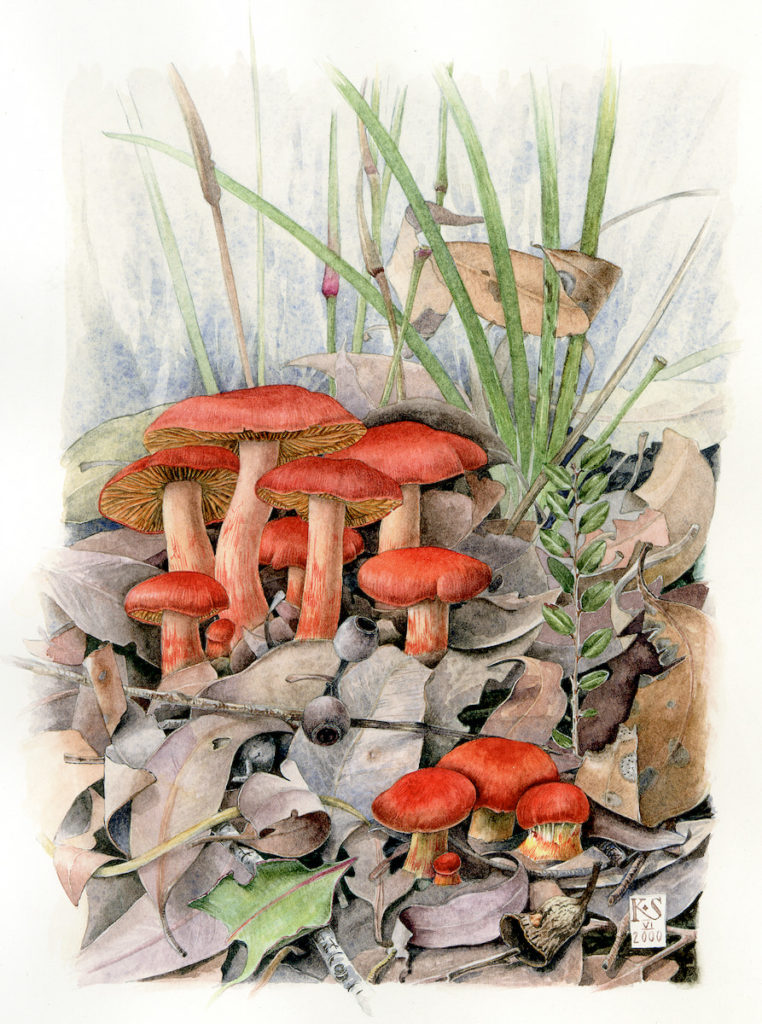

For decades, drawing and painting has been an inseparable part of Katrina’s study of fungi, and her ensuing botanical art has been widely exhibited. The rigour and detail in her work are incredible and impressive.

“Doing any sort of painting for natural history, you can show much more detail than you would with a photo. My finished paintings often depict the fungus within its own micro-environment, such as in leaf litter or on wood.

I did pretty accurate scientific drawings of plants when I was at school, but it wasn’t until I became fixated with fungi that my love of scientific drawing and painting was rekindled.

Mycology, which is the study of fungi, ‘happened’ for me after my husband Alex and I sold the farm at Wubin and had 5,000 dollars left over from the purchase of our Denmark home and small rural block. We didn’t do something sensible that would have sustained us for the rest of our lives; instead we went for a long holiday to Tasmania!

Alex, our two children and I drove over there from Denmark, fortuitously arriving in April, the best time for fungi. They were everywhere! I was amazed by the colours, shapes and textures: from miniature umbrellas to large shelving brackets bulging out from the side of a tree trunk. It was just fantastic. I kept a diary, and painted pictures of the fungi I found. I scoured bookshops for help with identifying them, but only found one book — about English species, which was not much use at all!

As a result, when we came home, I contacted the Botany Department at the University of WA to see if there was anyone who could help – and it was there that I met the wonderful Roger Hilton, a lecturer in botany and mycology, who became my mentor.

I organised for him to come down to Denmark to run a field trip near Nornalup. We found loads of fungi, but I was the only person in the group who was really, really interested in them. He gave me advice on the features to record and how to recognise different groups of fungi.

I went out most days through that winter, collecting fungi on our property and the adjoining old-growth forest, spreading them out on the kitchen table and neglecting housework! I came to recognise different groups, then species, by keeping records and making small colour sketches. I spent years learning about fungi.

In 1991, with funding from the Australian Heritage Commission, I drove to Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, staying for three days a week for a year, collecting and documenting fungi. I recorded 365 species and that was the beginning of my scientific research.

There’s really nobody else looking properly at fungi down here on the south coast. I feel it’s very important for me to do so, just to record what’s here.”

Extraordinary diversity is part of what delights Katrina about the world of fungi.

“The fungi I’ve found come in all the colours of the rainbow — there’s even the most amazing green one the colour of avocado flesh. We also have one that glows in the dark!

The shapes of fungi are also diverse, ranging from button-caps to coral-like fingers, iceberg droplets, brackets, jellies and extraordinary net-like structures. Some fungi species resemble a thin skin on bark or wood – like a smear of paint.

I love seeing fungi in all sorts of different habitats. You get to know them: when they appear, what they grow on and where. I take notes of everything, including the soil type and vegetation.

After carefully collecting an age range (from buttons right through to mature specimens) of a particular species, back home I lay them out, take photographs and collect a small sample for DNA analysis. I write a full description of each species, then dry the fungi at a low temperature in my dehydrator and pack each collection separately.

Using a high-powered microscope, I am able to record spore shapes, sizes and ornamentation and other structures which will help to identify species which might be new to science.

Of course, I enjoy the thrill of the hunt! I just grab my bucket, my waxed lunch wrap, some plastic containers, and my trusty truffle rake, then off I go to find fungi. I’ve made 3,234 fully documented collections so far, including a few bryophytes – and lichens from expeditions in the rangelands.

Strangely, even though I forget a lot of things, after all of these years, I can still remember where I found most of them — I can go back to that spot.

I’ve got to the stage where I need to consolidate a lot of the work that I’ve done. I want to get the information, including the fungi descriptions and photos, out to the different national park associations and other groups. I feel this will also help the burgeoning community of fungi enthusiasts across Australia who upload photos onto Instagram and iNaturalist. In fact, that’s a great way for people to start their own fungi journey.”

Walking through towering tingle trees, sunlit karris and crinkly casuarinas near Walpole, Katrina recalls some of her earliest collections.

“One of the first things I found in the forest behind our property, which was old-growth karri forest not burned since 1937, was a very strange thing that I called ‘mouldy marshmallow’. It was a soft white fungus with little blunt spines, greyish in colour with a blue tinge.

I didn’t know enough to write a description of it in 1983, but I did a little colour sketch of it. Twenty years later, I found a really good collection of these ‘mouldy marshmallows’ and sent part of it to the herbarium in Melbourne.

Then in 2019, when I was over at the herbarium working on fungi, I met a doctoral student researching a group of fungi including my ‘mouldy marshmallow’. It amused me that he even titled his scientific paper ‘The Mouldy Marshmallow’, and when I told him that its colour resembled blue cheese, he named the species Amaurodon caeruleocaseus, which is Latin for blue cheese!” So, I’m a bit chuffed that this is one of a number of my finds which has now been scientifically named and described.

Even though there are more fungi than plants, and many more fungi than vertebrate animals, there are few mycologists working in Australia. This means that not enough of our fungi are known to science.

Because there aren’t many people looking at fungi here in WA, it’s easy to go out and find new species. When I lived on our Denmark property, I could just open my front door, climb over the fence into the forest, find a few undescribed species of fungi, come back and have a cup of tea. Of course, you do have to do the detective work to be sure that what you have found is a new species – but that’s also part of the treasure hunt!

One of the lovely new species I found in 1991 at Two People’s Bay had a greyish cap with purple gills underneath. After finding it again at William Bay National Park, I sent a duplicate collection to mycologist Dr Teresa Lebel (then in Melbourne); the DNA analysis revealed that it was a genus new to Australia. Teresa helped me write the scientific paper, officially describing and naming it Asproinocybe lyophylloides. Being one of the authors is quite exciting!

Teresa and I are now collaborating on other undescribed species I’ve found, including a specimen from one of my favourite places in the Walpole-Nornalup National Park – long-unburnt, old-growth red tingle and karri forest on Douglas Hill.”

Further along the Walpole track, Katrina pauses in the presence of a huge sheoak (Allocasuarina decussata), furrowed with ridges of bark. Gazing from eye level down to its roots and the surrounding ground cover, she points out a fern and several species of fungi, lichen and moss living at different heights.

“Just beautiful! In the absence of fire, this sheoak’s bark has developed wonderful cork-like fissures, which are supporting a variety of life. They are trapping moisture as well, which allows it to host all these different organisms. This place is really healthy for fungi, too.

Even though I can’t see any fungi on the ground, I know they are just below the surface.”

Katrina explains that the ‘mushroom’ part of a fungus that we see, is really just the tip of the iceberg.

“Most of the fungus is living inside the substrate ‒ the soil, leaf litter or wood ‒ doing its job of rotting it down. The ‘mushrooms’, which usually appear after rain, are just the part that produces the reproductive spores which are released into the air.

But fungi are busy all year round through their mycelium – the little threads that form a busy transport network in the soil.”

Katrina continues through the forest. Her words paint a picture of the role of fungi in ecosystems, and how vital they are to the health of the plants and animals ‒ including humans ‒ around them.

“If it wasn’t for fungi, we’d all be wading knee-deep in muck.

Nature relies on saprotrophic fungi, which are the great decomposers and waste managers; they recycle nutrients and pave the way for other organisms to germinate and grow.

Some people call dead wood and leaf litter ‘fuel’ for wildfires ‒ meaning something bad ‒ but it’s not fuel, it’s food for saprotrophic fungi and other organisms, which rot it down and return the nutrients to the soil.

Other types of fungi, known as mycorrhizal species, have mutual life-support or symbiotic associations with 90 percent or more of plants ‒ it’s an incredible story.

The fungal mycelial network secretes enzymes into the soil and slurps up the resulting nutrient and mineral soup. The mycelia are widespread in the soil and gather nutrients over large distances — much further than tree and other plant roots themselves can reach. They are also much finer than the tree roots, getting into nooks and crannies that the tree roots can’t access. The mycelial threads then enter or surround the fine root hairs of these plants, delivering the nutrients the fungi have extracted, receiving carbohydrates as sugars in exchange (the plants produce these sugars by photosynthesis).

Remarkably, the mycelia also protect the plants from pathogens. Proteaceae, including banksias, do not have fungal partners, which is why they are so vulnerable to dieback.”

Not all fungi appear above the ground. In soil, leaf litter and ground cover, marsupials dig and plough in search of underground, truffle-like fungi.

“In Australia, we have more species of truffle-like fungi than anywhere else in the world. They’re generally very small and are dug up and eaten by a variety of native animals, particularly woylies and potoroos (ngilgytes), but also southern brown bandicoots and quokkas. Even possums will come down to the ground to dig up truffles. The thing about these truffle-like fungi is that they cannot spread their spores without something eating them!

The critically endangered potoroo has a diet that almost entirely consists of truffle-like fungi. When these fungi are ripe, they release a perfume that is picked up by the animals foraging for them.

I collect samples of truffle-like fungi in old film canisters, which concentrates the odour. When the canister is opened, you can smell the fungus — one smells like a bag of sweets, another like shoe glue. There are other not so pleasant smells too!

As most of these fungi-foraging animals have disappeared from the environment, the spores of the truffles can’t be spread. This doesn’t bode well for the health of the forest and other natural environments, because most of these fungi have symbiotic mycorrhizal associations with plants and the trees.

There’s another major benefit of animals digging for truffle-like fungi, which stems from their name ‘ecosystem engineers’. They dig and turn over the leaf litter and soil, creating little dips and hollows that seeds can fall into and germinate, as well as helping rain wet the soil. Before habitat loss and the introduction of cats and foxes, there were many more of these small, digging marsupials in the bush, so the country would have been less flammable.

It’s incredible how much good fungi do and how many things are reliant upon them. They are the silent achievers. Oh, yes, just one more interesting example are the seeds of our native orchids ‒ these need a fungal host in order to germinate.

As you can see, there wouldn’t be life on Earth without fungi. They are a part of the ecosystem and you need every part.”

This story comes from Menang and Pibelmen country. We acknowledge the extraordinary knowledge Menang and Pibelmen people have of not just fungi but of how ecosystems work.

THANKS to Katrina Syme, Josephine Hayes and the photographers. Editing assistance by Margaret Robertson, Dr Teresa Lebel and Keith Bradby. Photo editing by Carol Duncan. This story was published in the October 2023 edition of the Southerly Magazine, which is available online.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Publications featuring Katrina’s botanical illustrations and fungi knowledge:

- ‘Mushrooms & other Fungi of South West Western Australia’ (2018) by Sapphire McMullan-Fisher and Katrina Syme, published by the WA Naturalists’ Club

- ‘Brush with Gondwana‘ (2013), an illustrated book featuring seven botanical artists, including Katrina Syme, and their artworks of flora, fauna and fungi (Fremantle Press)

- ‘Survey of Fungi in the South Coast Natural Resource Management Region (2006-2007) is available here

- ‘Survey of the larger fungi of the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve’ (1992)

- ‘Fungi of Southern Australia’ (1998), illustrated and co-authored by Katrina Syme, with Neale L. Bougher

Other information:

- Fungi Study Group | Western Australian Naturalists Club (wanaturalists.org.au)

- Gilbert’s potoroo/ngilgyte (Potorous gilbertii) – critically endangered status, biology and threats

- Gilbert’s Potoroo Action Group website