Learning Noongar through Connection to Country

June 2025

NATALIE CORDON (nee Shanhun) tells of the joy and value of teaching Noongar language. She explains that her school students love learning Noongar because it comes from Country and is directly relevant to their lives. They hear the kulbardi (magpie), see the yoorn (bobtail) and walk in dooly (misty rain). First, Natalie describes some of her rich family history and the experiences that have helped shape who she is.

Albany, Mount Barker, the Porongurups and now Hopetoun are all home to me, but my family’s story starts in China. My paternal great-great-great-grandfather, Cheong Shin-hun, left Canton in 1852 and headed out to Victoria in a little boat for the gold rush. He met an English lady, Ellen Bolton, and they had twelve children together.

There was a lot of stigma surrounding mixed race marriages back then, so he changed our surname by deed poll in Victoria to Shanhun, taking out the hyphen and changing the ‘i’ to an ‘a’. His descendants, including my great-grandfather, Arthur Victor Shanhun, came over to the Porongurup area. Arthur married Alice Shenfield, one of the first teachers in Albany.

They farmed a lot of land in the Woodburn area, near the eastern end of the Porongurup Range – there’s a Shanhun Road out there now. For many years, my dad Ken and Uncle Max farmed sheep and cattle in that area, with my grandad, Arthur ‘Mick’ Shanhun.

My mum, Jenny, was born in Dumbleyung. Her father (my Poppa), Alan Lewis, was a farmhand in the Dumbleyung area. In 1959, he and my Nanna Josephine moved to the Porongurups where they had bought an apple and stone fruit orchard. My Mum and Dad were both students at Mount Barker High School and met on the school bus.

My brother Michael and I grew up on the farm. My friends used to ask, “Isn’t it boring living on a farm” and my answer was “No, we always have something to do”. Wildflowers were my thing. We had an abundance of wildflowers on our property: cowslips, fringe-lilies, sun orchids, donkey orchids and spider orchids – we‘d get excited when we saw a spider orchid! We had some good patches of brown boronia, which Grandad Shanhun used to pick and sell in bunches at Green’s lotto kiosk in Albany’s old Coles Plaza. I just loved the bush and bushwalking.

When I was 13, my parents sold the farm and we moved into Albany, but every school holidays we still went out to Pallinup Beach where Mum, Dad and Grandad Shanhun had built a shack in 1969. I absolutely loved it there. My grandad worked on the salmon run with old Bill Cagnana and was part of setting up the salmon camp.

I left school in 1988 to start a hairdressing apprenticeship. In the 1990s, hairdressing, travel and raising children were a big part of my life. But in my heart I still wanted to be a teacher. In 2000, I began a career as a Special Needs Education Assistant which remains a large part of my work.

I had retained a lot of the Noongar friendships I made as a student at Mount Barker primary school and at high school in Albany, and those friends have been really supportive and accepting of what I do now, which is teaching Noongar language. It’s lovely to have their blessing.

I am currently employed by the Department of Education as a Primary Teacher of Indigenous Languages. There’s quite a personal story leading up to my current employment.

Between 2005 and 2010, I worked as an Education Assistant at Mount Barker High School and gained my Certificate 3 in Education Support. With my passion for every child to have an education, I volunteered a lot of time at the school. In 2006, the school principal, Jonathon Hoskins, asked me if I wanted to work with the children of Hazara refugees and support them in their classes. A lot of Hazaras had fled the war in Afghanistan and some made their way to Mount Barker to work in the vineyards. The students (and their parents) could not speak English and they could not read or write in their own language.

Teaching these students was challenging because they had no foundation for learning whatsoever. I wondered, “How am I going to do this?”. There were no teaching resources so I found a Farsi dictionary and started with that. Farsi was one of many dialects they could understand. The students could not read or write Farsi or Hazaragi, but they could speak it.

The only way I could teach these students English was to learn words and phrases in their language and then translate them to English. It was fun because they’d laugh at me when I’d try to say a phrase like “khuda hafiz dostman” (“goodbye, my friend”) out of the dictionary but my pronunciation was wrong. They taught me a lot as well! About their culture, their homeland, and their plight. I became part of their families and every Thursday night I had dinner with them. They were such beautiful and hospitable people. They changed my life and my view of the world.

At the end of the year, I received the annual Principal’s Award for my work with the Hazara students, which was very humbling. So all that was a really beautiful experience for me and it probably set me on my journey to where I am now.

That same year, and the next, I also worked as an Education Assistant in the school’s Noongar LOTE (Languages Other Than English) classes, which Joy Ugle had started teaching. We went out to the Porongurups and collected big coffee rocks to make a yarning circle for the classes.

That’s when I started learning the Noongar language. I basically taught myself after that – I bought a lot of books and did a lot of research. My connections with local Noongar people also helped me to learn the language. Then in 2023, I completed the Noongar Language and Culture course through Curtin University. This year, I’m doing three Undergraduate courses: ‘Language in Aboriginal Australia’ through La Trobe University; Murdoch University’s ‘Two Way Science’; and ‘Introducing Indigenous Australians’ with Macquarie University.

I moved to Hopetoun in 2023 and began a new role as a Special Needs Education Assistant at Hopetoun Primary School. I explained my passion for the revival of Noongar language, and the school gave me the opportunity to teach it. They suggested and supported my application for ‘Limited Registration’ to become a Specialist Teacher, as well as a Relief Teacher. I really appreciated the opportunity.

After applying for a position at Ravensthorpe District High School for 2024, the principal, Mat Kennedy, offered me a role as Special Needs Education Assistant and the opportunity to bring Noongar Language to Ravensthorpe, with my own classroom. That felt like, oh my goodness, someone’s looking out for me!

My role as Noongar Languages Teacher at Ravensthorpe started with Years 3 – 6 and in Term 2, I began teaching the Year 1-2 class for one period a week. That was wonderful because the little ones just soak it up – it’s the best age to teach them. They absolutely love it.

The school has an incredible Reconciliation Action Plan and a cultural team, which I’m a part of. Even though we don’t have many Noongar students, or Indigenous students, the school is embracing this culturally inclusive approach.

I’m in my second year of teaching Noongar at the school and I just can’t believe how well it’s been received. What we do is immersive, it’s not just about the language. I approached the principal about establishing a bush tucker garden to support the cultural and language learning experience and so I could take the classroom outside. We applied for a grant through Junior Landcare to set it up and it has been a huge success. Before we ordered the plants, the Year 5-6 students researched a plant each, such as how tall it grows and the best planting location. A lot of them come from a farming or regional background, so they loved that.

The thing I love about teaching Noongar is that it’s so cross-curricular. You’ve got the history, you’ve got the culture, you’ve got the place-based learning, two-way science, maths – you’ve got every subject in one classroom. And I think that’s what the kids respond to. Some kids love science, some kids love learning languages, some kids love being outdoors and gardening, so it caters to so many different personalities and so many learning capabilities.

Noongar is an oral language and it comes from Boodja (Country). It’s not like teaching a European language or Japanese. With Noongar, you’ve got to teach the connection between the language and Country – that’s where the words come from. As an example, the name djidi djidi (willy wagtail), is because of the cheeky ‘chitter chitter’ sound that it makes, so it’s very important for students to learn about Country first and then learn the language.

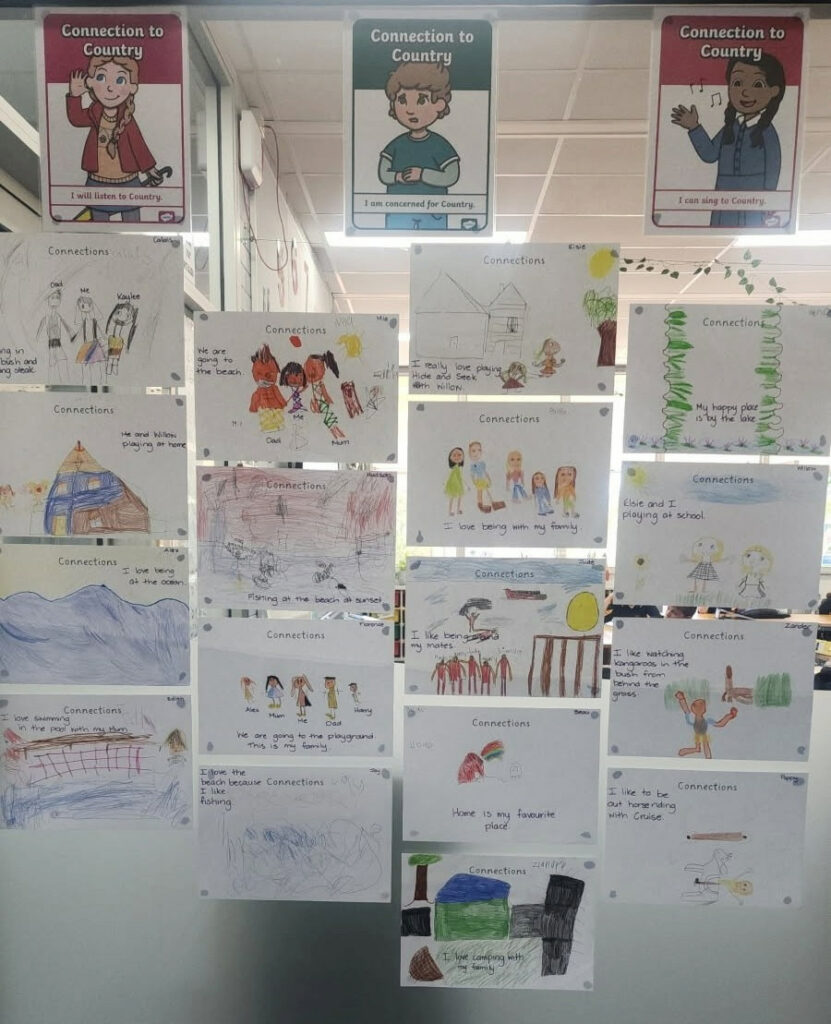

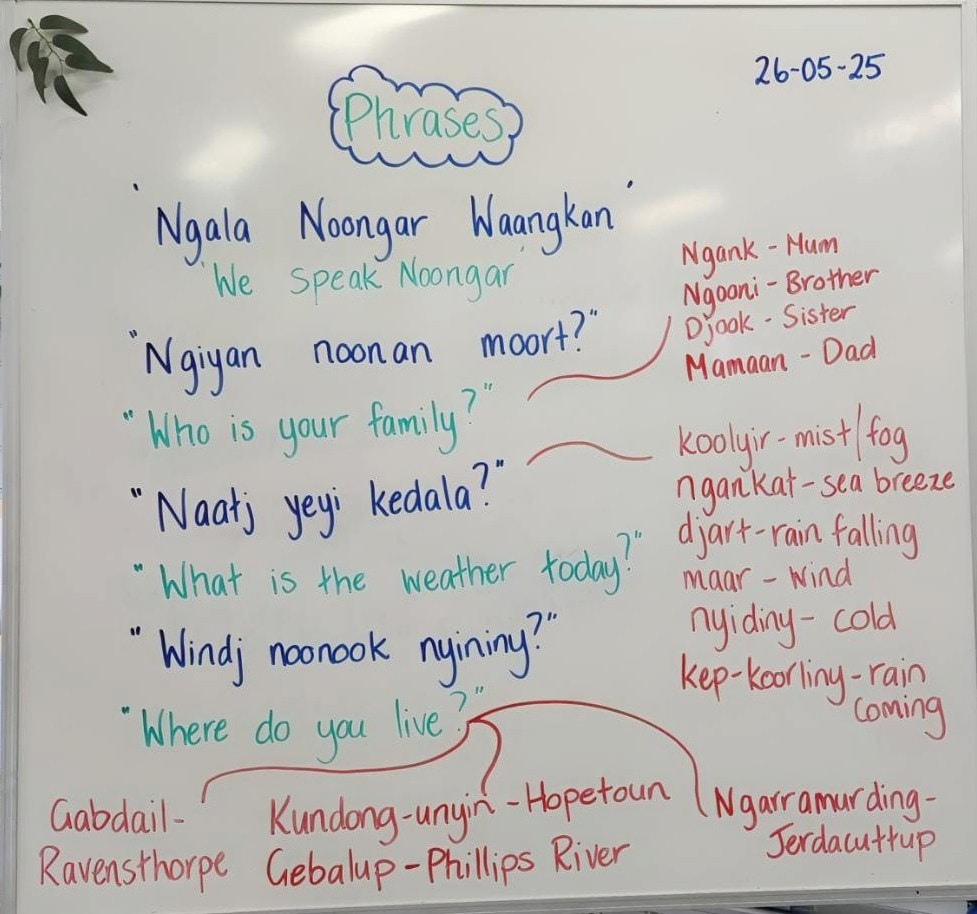

At the start of the year, to lead students into Connection to Country, I ask them to sit and think about a place, a person or a thing that they have a connection to and makes them feel happy, safe and good. They draw a picture and then they write about it – I scribe for the younger ones. You’ll see the walls of my classrooms are covered in this work. That leads on to a class discussion about why Connection to Country is so important to Noongar people: it’s a place where they feel safe, it is their home, it makes them feel happy and it is about belonging. This is a really good way for the kids to get that understanding. And then we go onto the next topic which is moort – moort is family. So we learn all the family words. We don’t go straight into phrases and sentences because they need to learn the basics and the words first, but we’re going into our second year now and the kids who learnt Noongar last year, and some the year before at Hopetoun Primary School, are getting really good – really good!

I greet every class in Noongar, even when I’m working in a mainstream classroom. I always say, Kaya wanju, moorditj coolangaar (Hello, welcome wonderful students), and they always respond to me in Noongar. The little kids love it. And even in the playground they always say hello or goodbye to me in Noongar.

After our greetings, I’ll usually ask “Noonook moorditj?”(how are you), and a student might say “Ngany bidibaba”, which is, “I’m tired” or “kwob” (good). They know all the emotions and feelings in Noongar.

After doing some language work inside, I like to take the learning outside. This is important because after we’ve covered the first-term topics of connection and family, we go into the marlak, which is the bush, and this ties in with our bush tucker garden. We talk about, and the students learn, the Noongar names of different boorn (trees), djet (flowers) and mereny (edible plants). They learn about the six seasons, and any djerap (birds) we can see. The students have written some incredible stories about the bush – in both Noongar and English.

A special moment for me last year was our school “Learning Journey”, which is like an open night. The kids produce a lot of work and I love displaying it in the classroom. I guess I was a bit worried about whether members of the farming community were happy that their kids were learning Noongar. I know that sounds silly, but you do think of those things. So I was sitting in my classroom, which was completely empty, and thinking, “Oh, gee, no one’s going to come in here”. Naturally, they had gone to their child’s main classroom first, and all of a sudden, when they’d finished in the main classrooms, they started coming in and oh, it was lovely! They were looking around at all the work, they sat down with their children and their workbooks, and the kids were flicking through and showing them and reading words out in Noongar and explaining different things. Noongar classes were on a Friday and I remember one of the mums, who had a child in Year 1 and another in Year 3, saying to me, “Oh my goodness, it’s all they talk about on a Friday when they come home from school – they just absolutely love it”. I saw a couple of the kids sit down with their farmer dads, read them books and show them their work. I walked away from that evening feeling great and thinking, “Yes, the school community has embraced it as well.”

I think the kids find the Noongar language classes so interesting because of the connection: Noongar is Australian, it belongs to our area. It is part of where we actually live. I think that really excites them.

The little pre-primary kids always say kaya kulbardi (hello magpie) when the magpies come around for lunch. They can relate Noongar language to things they walk outside and see. They say hello to the yongka (kangaroos), which feed on our school oval. Everything is here – a lot of the words they are learning about describe things that are present in our community and on their farms. It’s that whole connecting to the country where we are, to our area – the language ties in with everything. I think that’s why they love it.

They also love the Noongar creation stories. I explain that the Nyitting – the Dreaming – and its creation stories are like a religion. We all have different religions and different beliefs, and this is the Noongar belief system.

In March 2024, the principal and I met with Roger Erith from the environmental organisation Gondwana Link about the school’s possible involvement in the Genestreaming Journey Sculpture project. This project is about bringing together culture, science, biodiversity and art in a sculpture trail. Roger raised the idea of the students creating Noongar paintings that would form part of a sculpture for Ravensthorpe. We explained that we didn’t have many Noongar students here to do the art but asked whether we could involve our students who were learning Noongar. Roger checked with Aunty Carol Pettersen, a Menang-Gnudju Elder and co-founder of the sculpture project, and she embraced the idea.

In June last year, Aunty Carol made her first visit to our school. She told the kids about how the popular Willow Pattern plates feature Chinese-inspired motifs and how the Noongar people also told their stories through art symbols. She spoke beautifully about the songlines and the trails, the bidis, of her ancestors. She told them about her grandmother and her totemic connection with talyeraak trees (Eucalyptus pleurocarpa) and the yirdah bird (western spinebill). The kids connected with Aunty Carol so well – they had never met someone like her.

She told them that she lived in the bush until she was 10 years old and the kids were like, wow, this is like a lady out of a movie. The questions they asked her were great, like “How old were you when you saw your first white person and what did you do?”. Aunty Carol explained that she thought the first white person she saw was a policeman. She and her brothers and sisters had been hidden away in the bush by their parents so they couldn’t be taken away. So as kids, they thought that all white people were policemen.

On that first day, Aunty Carol and I talked about how to involve the students in creating artworks for the local Genestreaming Journey Sculpture. We wanted them to create their own stories about where they come from – the country around Ravensthorpe. We wanted them to make that connection. Even if they couldn’t write it or speak it, they could express it through art. It’s really special that they were allowed to use Aboriginal symbols to do that.

In the school’s art room, accompanied by art teacher Niki Crane, Aunty Carol was just fabulous, mingling with the kids and listening while they talked about their ideas for their story. She didn’t influence any of the stories, they all came from the students themselves. They produced these stories as fantastic artworks and now ten of them are part of the sculpture that was launched just a few months ago in Ravensthorpe’s main street.

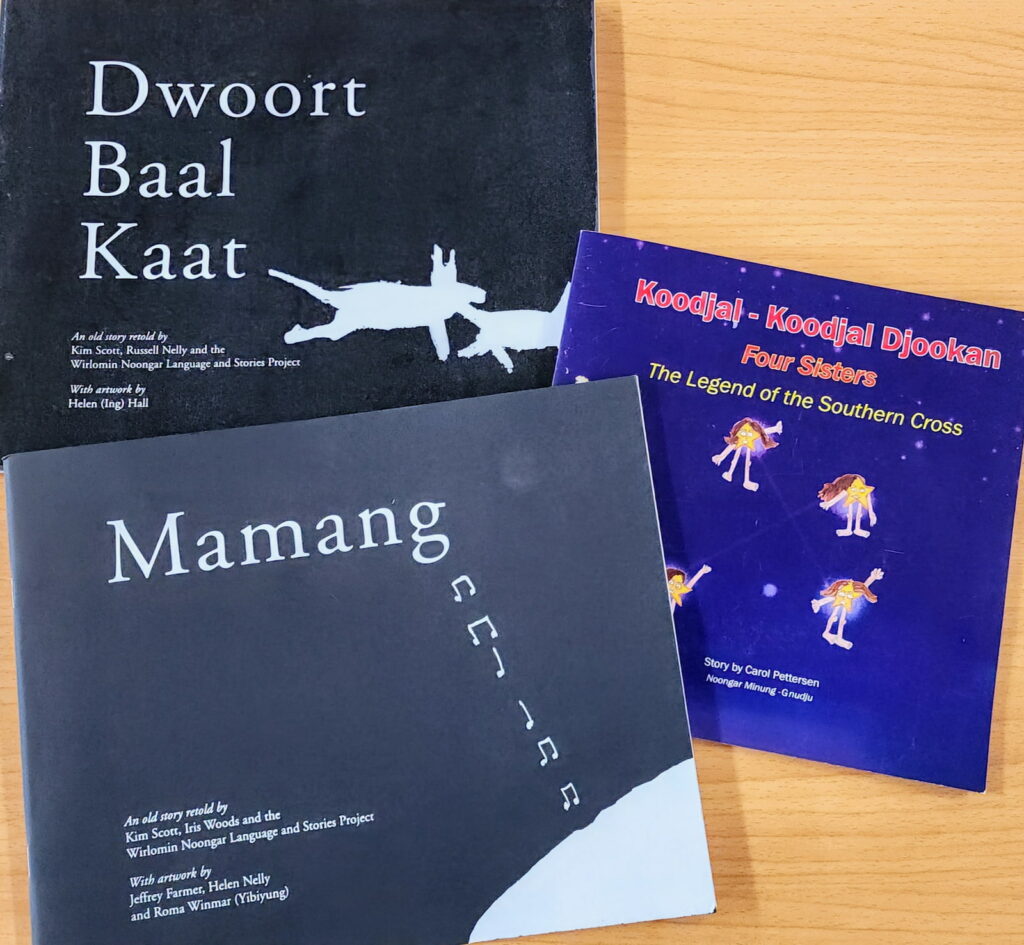

Although at that point I had taught just one term of Noongar language with the Year 1-2 students, their teacher, Sue Dee, really embraced this language work and the Genestreaming sculpture project. She went as far as doing a life-size artwork with the students for one of the sculpture’s bracts (or ‘petals’). I had taught the class two creation stories written by Noongar author Kim Scott and a third by Aunty Carol. The kids just loved these Noongar stories, so Sue and the students incorporated all three into an artwork for the sculpture – it is incredible.

Our goal with the Genestreaming sculpture project was that Connection to Country – connecting to Boodja that we live on. We wanted the students to embrace where they live, to learn more about it, and to include that in their stories. And I think the language did that, the art did that and having Aunty Carol speak to them about her own experience on country did that.

She also talked about how important it is to look after Country. Everything used by Noongar people came from Country and it’s been looked after this long for us to get to where we are now, and we need to keep looking after it. So it has opened that whole environmental stewardship door for our students. We want them to see that, yes, we need farming and we also need to look after the country. That really came out in a lot of their stories.

I think we were just so lucky to be a part of the Gondwana Link Genestreaming sculpture project, and the kids could really see it – they really embraced it. I think it has changed their outlook on their Connection to Country and looking after Country. It made them realise what a special place we live in, the Fitzgerald Biosphere Region.

Aunty Carol’s involvement was a koomba (huge) thing for us. I was sharing knowledge with the students but having Aunty Carol come in and speak from her perspective, her history, her experiences, opened their eyes even more. The kids just love listening to her talk. They’re in awe of the fact that she grew up in the bush. She’s a celebrity to our kids and has become our unofficial cultural ambassador. We’ve adopted her as our school’s Aunty, and as soon as the kids see her, they excitedly call out “Kaya, Aunty Carol”, which of course she loves.

I hope the Noongar language will thrive and become like a second language throughout south-western Australia. That’s my dream.

We respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the Ravensthorpe area.

For Ravensthorpe’s Genestreaming Journey Sculpture, we thank major supporter Lotterywest, along with the Ravensthorpe Shire, District High School, Herbarium and community, and ALL other contributors noted here. Special mention to Roger Erith, and to Genestreaming project co-founders Ben Beeton and Aunty Carol Pettersen, together with Mali Moir, Gary Muir and Mark Hewson, who made and researched the sculpture. To learn more about the sculpture, visit here.

For this story, THANKS to Natalie Cordon, Carol Pettersen and the photographers. Editing by Margaret Robertson, Keith Bradby and Stephen Mattingley. Photo assistance provided by Carol Duncan.

REFERENCE MATERIALS

Gondwana Link has produced this two minute video about the botanical importance of the Ravensthorpe Range, featuring Professor Kingsley Dixon and local botanist Merle Bennett: ‘Ravensthorpe – Wonderland of Plants‘.

A descriptive story about Ravensthorpe’s Genestreaming Journey Sculpture is in the local ‘Community Spirit” newspaper, here (Issue 05, 27 March 2025, pp. 10-15).

Ben Beeton, co-founder of the Genestreaming Journey Sculpture trail project, has a SciArt website containing a rich library of imagery and information about Ravensthorpe’s sculpture.

A written story about Aunty Carol Pettersen is available here. And you can hear Aunty Carol in this podcast. Both stories are on Gondwana Link’s Heartland Journeys website.

The three Noongar creation stories mentioned in Natalie’s story are: