Peat, Fossils, Palaeohistory + Art

Red tingle and red flowering gums, peat swamps and pollen fossils — all this magic is focused in the precious and glorious Walpole Wilderness Area and our storyteller is DR ELIZABETH EDMONDS. Elizabeth lives an incredible life as a scientist, artist and gallery owner. Here she explains how she’s weaving together these threads with the aim of protecting the places, plants and wildlife she loves.

Story by Dr Elizabeth Edmonds

If I’d been asked twenty years ago what I would be doing today, I wouldn’t have imagined that I’d be combining two careers into one – art and science. Now, my palaeo-environmental studies involve collecting and looking at microscopic fossil pollen in peat sediments, and these same materials are inspiring me as a visual artist. The pollen and peat samples I study are thousands of years old and I am using these same pollens and peats to create landscape paintings that are literally infused with time.

I grew up on the eastern seaboard, but I’ve lived on the south coast most of my adult life. Practicing my art and science in the incredibly beautiful Walpole Wilderness Area makes me one of the luckiest people in the world.

In 2016 my husband David and I opened Petrichor Gallery in Walpole as an events-based gallery to showcase the diverse and outstanding works of regional artists. The Gallery’s ethos also reflects our passion for the natural environment and the value we place on community engagement across the arts, science and nature. Through the visual arts we celebrate and raise awareness of the extraordinary importance of what is around us — the Walpole Wilderness.

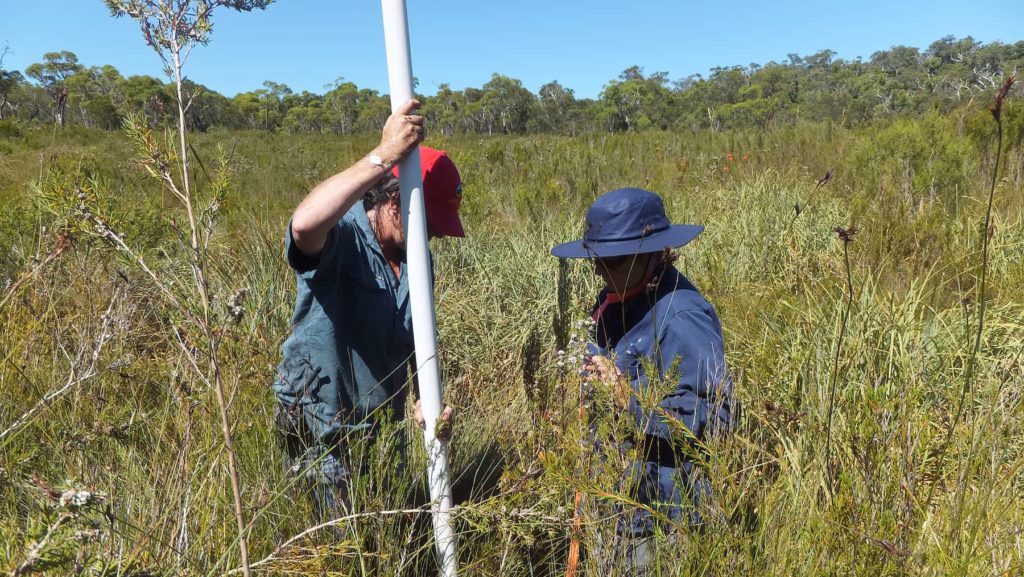

My appreciation of the Walpole area began in my university undergraduate years through a research project at Boggy Lake in the Nuyts Wilderness, west of Walpole. On a cold wet wintry day in 1991, some university colleagues and I ventured out to extract cores of sediment from this small heavily vegetated lake. Wading up to our waists in icy water to retrieve over three metres of peat material and then getting it all back home for pollen analysis was an experience. But I was hooked!

Boggy Lake introduced me to the world of palynology, the study of microscopic plant pollen, spores and other microfossils (or palynomorphs). Guided by my university lecturers Karl-Heinz Wyrwoll and Jane Newsome, I began looking down a microscope at fossil pollen in peats to reconstruct vegetation histories. It’s a way of understanding how landscapes, the environment and climate has changed over many thousands of years.

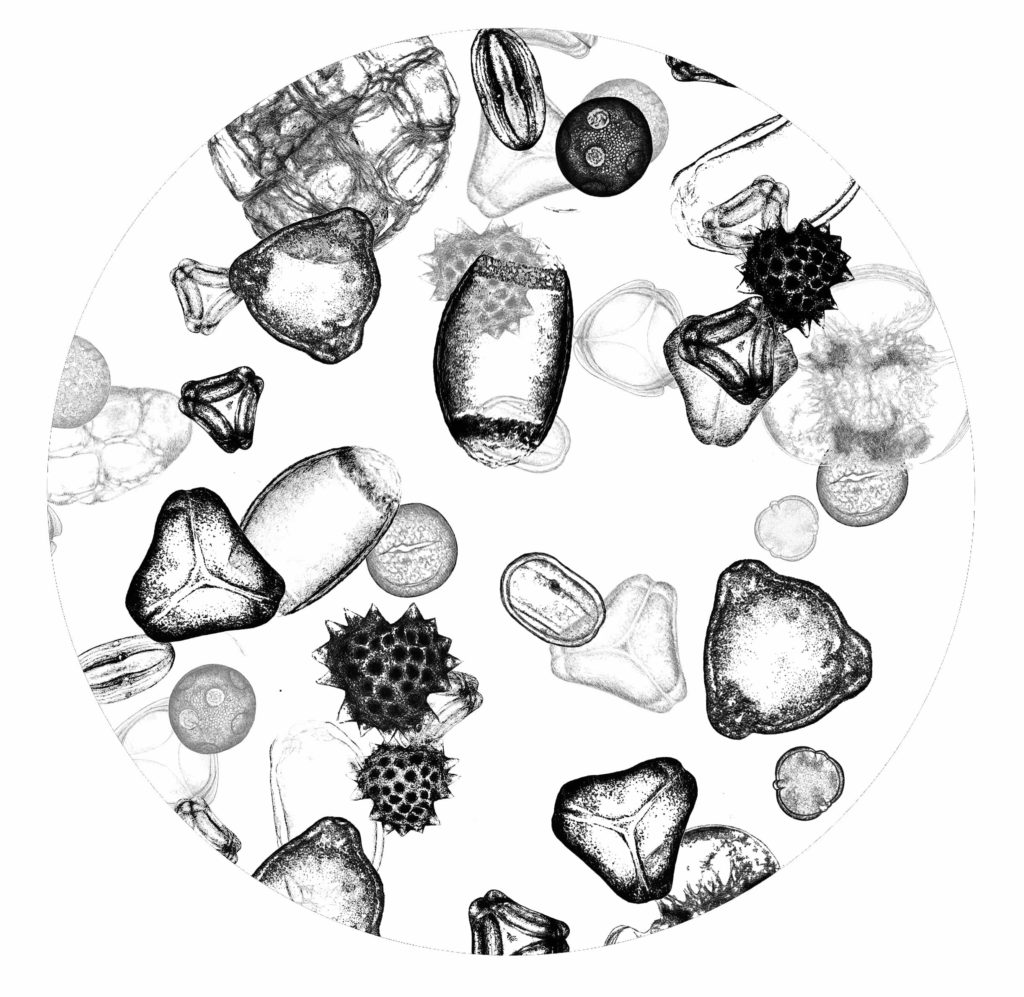

Once you have a sediment core, sample material is prepared for chemical analysis and radiocarbon dating. Then it’s a matter of looking through a microscope and counting different types of pollen grains at different depths, down through the core, which means I was travelling back through time for thousands of years. And we are talking lots of pollen: with each core I’d count multiple slide samples of material containing hundreds of different pollen types.

Looking at pollen is so fascinating as every plant species has its own unique pollen signature revealed in the pollen’s size, shape and surface pattern. Pollen is produced from the male anther as the soft powdery stuff that fertilizes the female parts of a plant. These grains have a hard cellulose coat made of sporopollenin that protects the grains indefinitely, making pollen ideal for fossil work.

It’s mindboggling to look down the microscope and see some of the environmental history of this place unfold. Each sample taken from a peat core provides a snapshot in time. Collectively, the fossil pollen in these samples reflects different plant communities, their species richness and changing ecological conditions over areas and across time. We can gain insights into vegetation structure (e.g. was it forest or shrubland), their geographic distribution and land use changes.

Exploring vegetation histories also made me aware of the significance of peat systems, not just for their ability to preserve environmental records, but how they act as major carbon stores and are important ecological habitats. Globally, there is now greater recognition of the role peats play. Peatlands cover just 3% of the world’s surface yet hold nearly one-third of the planet’s soil carbon. That means there is more carbon stored in peats than in all other vegetation types combined, including the world’s forests. Australia has an estimated 0.3% of the world’s peatlands and yet in the south-west we know little about their geographical extent, age, conservation and current condition.

Broadly speaking, ‘peats’ is a term used to describe a variety of soils with high organic contents, derived mostly from the accumulation of decaying plant material over thousands of years under conditions of waterlogging, oxygen and nutrient deficiency, and high acidity. They also provide specialised habitats for plants and animals that are tolerant of these conditions.

Peatlands are not only beautiful, dramatic landscapes teaming with life, they are also vital to the health of our natural systems. Peatland vegetation slows and filters the flow of rainfall in our water catchments, helping to purify water, prevent local flooding and hold sediments. In the southwest, mosaics of peat systems in lowland areas act as migration corridors for animals such as quokka. They are also often home to plants and wildlife that only occur in specific locations (endemics), many of which are what we call ‘Gondwanan relicts’. These are descendants of species that flourished tens of millions of years ago, and they have relatives in other southern continents that once formed the massive supercontinent called Gondwana. Local examples include endangered species such as the sunset frog, Albany pitcher plant, the recently discovered Walpole peat helmut orchid and some of the sedges.

However, peatlands are under pressure and are extremely vulnerable habitats. These living systems have persisted for thousands of years but the impacts of a drying climate combined with altered fire regimes, dieback disease, feral pigs and a mix of human activities over time are changing them permanently.

As an artist I am inspired by Australian landscapes, in particular the wilderness area and ‘peatscapes’ where I live. For some time I had been thinking about an exhibition to help raise awareness about peats, to celebrate them and the conservation efforts that are being made. It made sense for me to combine my art with my scientific background, so I approached the WA Museum of the Great Southern in Albany with the concept. They were wonderfully supportive, launching my PEATering Out exhibition in August 2021.

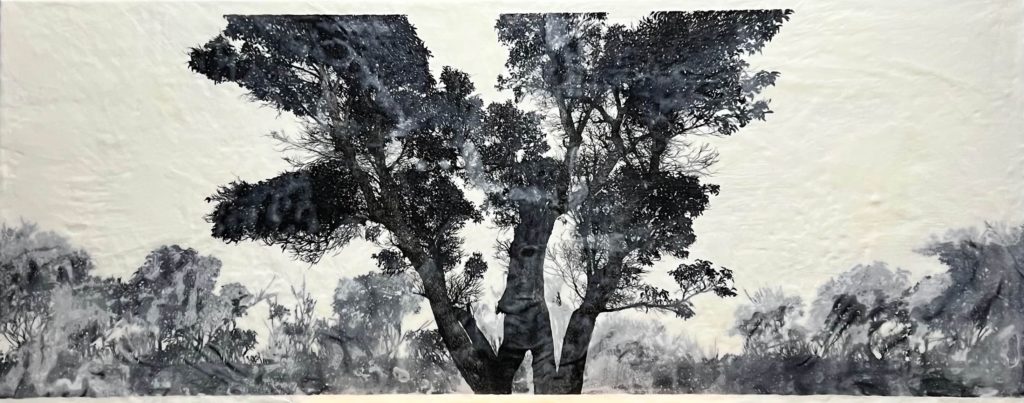

The idea for the exhibition was to use the peat from cores I’d collected at various locations along the south coast during my research years. Never really knowing what to do with the remaining material but not being able to throw it out either, I decided to make watercolour paint out of the peat. I had a play with the material, trying various recipes to create paints that were archival, pliable, water-soluble and functional. While I was used to scientifically describing and analysing peat under the microscope, making paint with it took my familiarity to another level. I felt I had come full circle with my art and research.

By nature, I knew these ‘peat paints’ would be special with their microscopic elements of pollen, charcoal fragments and other microfossils thousands of years old. The artworks became an environmental narrative, infused with peat and time. Through the peat stories in my paintings I was able to explore and portray the natural landscape’s many layers and depths.

The success of the PEATering Out exhibition has been a catalyst for more art/science projects. I am thrilled to have recently been awarded a 2023 Dahl Fellowship from the Melbourne based organisation Eucalypt Australia. This will enable me to explore, through my art/science practice, the environmental narratives behind two iconic Australian gum trees: the red flowering gum (Corymbia ficifolia) and the red tingle (Eucalyptus jacksonii). This work will culminate in an exhibition, Tale of Two Trees, to be launched in August 2023.

The red tingle (tingle tingle, Noongar name) is an unusual buttressing eucalypt with no tap root — a characteristic it has retained from a time when the south-west was a wetter rainforest environment. The red flowering gum (bilgie yutah bunnah, Noongar name) has also kept some characteristics that evolved in wetter times. They may have been more widespread but as south-western Australia has dried, the modern range of these two species has contracted to the wetter and cooler southern areas. Tingle trees are found only in small areas of the Walpole Wilderness and adjacent reserves, while red flowering gums occur around the Walpole-Mt Frankland region with a couple of smaller outlying populations to the east.

The Valley of the Giants Tree Top Walk has enabled millions of tourists to walk amongst the giant red tingle trees, while the red flowering gum is the best-recognised and widely grown gum tree on streets and in gardens throughout the world. Despite that, we still have more to learn about the ecology, biology and conservation status of both of these much-loved species. These trees, and the ecosystems they support, are under pressure from accelerated climate change, altered fire regimes, and a range of other human disturbances.

My Tale of Two Trees Dahl Fellowship is an amazing opportunity for me to research and explore my art practice further using ‘peat paints’. It will also bring together local knowledge through a community workshop in March 2023, with invited speakers and locals talking about these unique trees in connection with art, literature, science and their personal response. The overall aim of the Fellowship is to produce an ‘Exhibition Package’ that can be showcased in other locations, as a piece of art on the move, to help raise ongoing awareness of these special members of Australia’s family of gum trees.

Returning to the beginning at Boggy Lake, through our detailed study of pollen morphology, my colleague Jane Newsome and I were able to differentiate, with some confidence, both modern and fossil pollen of red tingle and red flowering gum, plus several other locally occurring eucalypts. From that work we can infer that eucalypts, especially karri, jarrah and marri, remained the dominant plants in the vegetation, along with the presence of red tingle and red flowering gums, over at least the last 4,500 years.

It’s often said that ‘to understand the future we need to learn from the past’, which makes me wonder what we will learn from future records that look back on the current period of rapid climate change, altered fire regimes and other impacts. I have my fingers crossed that the peatlands, red tingle and red flowering gums will still be here and that’s going to take a mighty conservation effort, both locally and globally.

Sincere thanks to Elizabeth Edmonds and the photographers. Editing by Margaret Robertson and Keith Bradby. To help with conservation efforts, please join the Walpole-Nornalup National Park Association.

Further reading:

‘A Tale of Two Trees: Red-Flowering Gum & Red Tingle’ – Exhibition Catalogue, Elizabeth Edmonds, September 2023

‘A Tale of Two Trees:’ – Exhibition artist statement, Elizabeth Edmonds, September 2023

Walpole-Nornalup National Park Association – a local community conservation group

Eucalypt Australia – a grant-making Charitable Trust focused on eucalypts; Elizabeth is one of their 2023 Dahl Fellows

Prof. Pierre Horwitz’s sunset frog story on the Heartland Journeys website

WA Botanic Gardens & Parks Authority: Red flowering gum

Wikipedia: Red flowering gum

Wikipedia: Red tingle