Grand plan for the Wilson Inlet Catchment

After working in seas across the world, Shaun Ossinger now focuses on the land while caring for an important area of water – Denmark’s Wilson Inlet. Gondwana Link’s Keith Bradby asks Shaun about his life and the dynamic program he leads for the Wilson Inlet Catchment Committee. Along the way, Shaun offers thought-provoking insights.

Keith: How did you become who you are?

Shaun: I was born in Seattle, but my family moved back and forth between Seattle and Alaska from the time I was a young kid.

My dad has been blind since he was 15, so he has never seen my mum but, with her help as a reader, he undertook a couple of university degrees. One of them was an oceanography degree, after which he worked for the Department of Fish and Game in Seattle. But by the time they had me, my dad was long out of fisheries and he was a motivational speaker for Amway. My parents had this big obsession with positive thinking and they used to travel the world together. My brother, sister and I often tagged along. It was kind of drilled into me from an early age: you can do anything. And I think in some ways I took that on board.

I grew up with a keen passion for the outdoors and the ocean. It was in year three, I think, that we had to design what we wanted to do for a living: “draw your house and describe your profession”. I drew a sailboat and said I wanted to be a diving instructor. I had this set of old Jacques Cousteau encyclopedias on oceans ‒ it’s 26 volumes and I had read them all cover to cover. I was about 10 at the time and I was fascinated by Cousteau’s life as an oceanographer and his co-invention of the “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus” – SCUBA.

I did my marine science degree in Hawaii. I was obsessed with undersea habitats, and I wanted to drive deep-sea submersibles for a living. I realised that I’d have to do further studies after my bachelor’s degree but I thought I’d take a break for a while. I headed back to Alaska and did crab fishing to make some money to travel and teach diving. I ended up living in the Caribbean for several years. I moved around the world teaching diving, in Egypt, the Red Sea, Israel and southeast Asia, so I got a love for travel and people. I ended up meeting someone from Perth when I was in the Caribbean and followed her back here in about 1996 (but that didn’t work out in the long run).

When I first got here, I couldn’t find a job in marine science. I had my diving background, so for several years I was a drift diver for Broome Pearls. One day we were in between dives and one of the big tyre fenders on the side of the boat was being pulled over the side. I grabbed the tyre but it twisted me. I herniated a disk and just went down in a heap and ended up having to get carried off the boat on a backboard. They lifted me off the wharf with a crane, put me in the back of an old ute and took me to Broome hospital.

Some weeks later, I was on workers compensation and sitting in the Broome Pearls’ yard splicing rope when somebody gave me an advertisement in “The West Australian” which said Fisheries is hiring. I thought “Oh, government, that’d be better, never having to work physically again”. So I ended up becoming a fisheries officer and did mainly abalone compliance between the South Australian border and Windy Harbour, near Northcliffe.

I met my wife Corrina when we were doing an operation that involved the airports, looking at illegal abalone going overseas. To get behind the scenes at Perth airport, you had to be with a customs officer and the officer I was assigned to was Corrina. A couple of weeks later I got this random email from her that said, ‘Oh, do you want to have a coffee?’ And here we are now, with two children.

Even though being a fisheries officer was heaps of fun and I met a lot of people, it wasn’t where I wanted to be for the rest of my life ‒ compliance never really sat well with me and I wanted to get back to science. So I joined the Australian Fisheries Management Authority and eventually managed the turtle and dugong fishery up in the Torres Strait.

Corrina was also working for the Feds up there so we managed to buy that sailboat I had always wanted. We bought a sailing catamaran in Airlie Beach, Queensland, and sailed it up the Great Barrier Reef to Thursday Island where we were living. But then we thought, “There’s no point in having a boat if you don’t take time to enjoy it”, so we took leave from our jobs and sailed throughout southeast Asia, living on board for four and a half years. Our eldest son Keshi learned to walk on the boat which was amusing to watch. When we came back we worked for the Federal Government again in Darwin.

But that whole time I really wanted to move back down here. I love Denmark and the whole south coast. So we ended up getting a house in Denmark and I was fortunate enough to land a job with Parks and Wildlife managing the Walpole and Nornalup Inlets Marine Park.

Really, you manage estuaries from the land, not from the water – you monitor them on the water but they’re a product of what happens in the catchment area. And so, when I was running the marine park, I was working with farmers and I fell in love with them.

I realised pretty quickly that when you’re doing a marine job for Parks and Wildlife in Walpole, fire comes first and that didn’t sit well with me. So in 2015 I got out of that job and saw an advertisement from the Wilson Inlet Catchment Committee (WICC). They were looking for a part-time project officer.

That was a natural transition for me and I think this was probably the first time where I found some elements of a calling. I think all that diversity of experience and background, including working for multiple government departments and understanding that system, as well as my education, has been really vital to what I can bring WICC.

I think being a generalist is underrated. Having been around the traps and not going down any road to the point of being specialised is actually something that should be embraced because it’s the generalists who can actually put the pieces of the puzzle together. They see how people work and how systems work and so they can make very effective managers.

Keith: Tell me about the Wilson Inlet catchment.

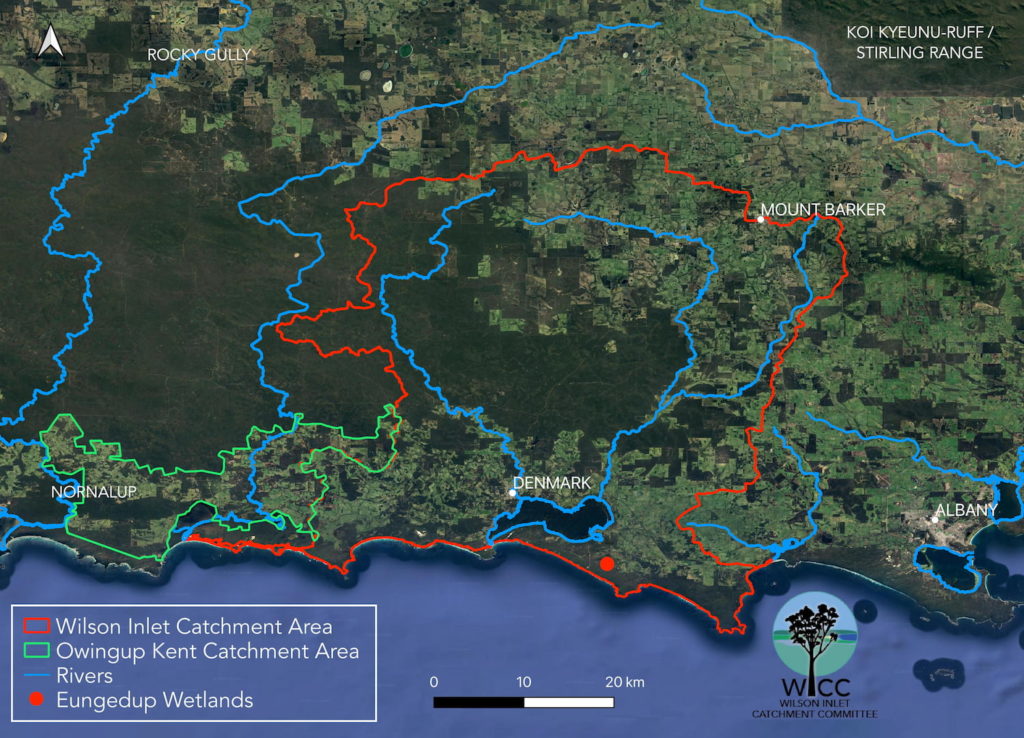

Shaun: Wilson Inlet is next to Denmark and its catchment goes as far north as the Mount Barker area. We work all the way out to West Cape Howe in the east and we’ve extended our work to Nornalup in the west, so it’s a fairly large area. The point sources for nutrient export, which are the biggest focus for Wilson Inlet, are on agricultural lands in the lower catchment, so around Youngs Siding and the Cuppup and Sleeman sub-catchments. We have been working a lot on the lower catchment for the last five or six years. However, I’m also really keen and committed to building a useful focus in the upper catchment areas.

Keith: What has been your role in the Wilson Inlet Catchment Committee (WICC)?

Shaun: The WICC board gave me a lot of latitude from the first, probably because they just didn’t have the time to manage anyone. That’s the environment that I thrive in ‒ not having many boundaries. I had come out of government and I was disillusioned with its lack of efficiency at times ‒ so many things that just didn’t make sense. So to be given the reins of WICC, even though it was quite fledgling at that time, to build something that made sense and to do projects that were scientifically based and had the backing of the community ‒ I just became addicted to it.

We’ve been building up WICC, but when I say “we” it’s definitely not just me. Maybe in that first six months it was, but after that, we managed to attract a fantastic board of directors. We have spots for 10 people on our board and they’re full and there’s a waiting list now. They’ve all been selected to fulfill certain functions to give WICC credibility and strategic direction, and they provide a lot of specialised support as well. I think a key strength of WICC now is actually the board.

In my first year I just hated board meetings. Now, it’s completely the opposite, I love board meetings. They’re a chance to go “Look at this exciting work we’ve got going on and there are so many cool things afoot at the moment”. Board meetings now are more of a celebration. I also like getting that strategic direction and insight.

We restructured WICC with the help of the highly experienced planner Paula Deegan, who is now on the board. We decided to focus WICC on three pillars: sustainable agriculture, biodiversity, and waterways and wetlands. The plan was to get an expert in charge of each one of those pillars. My job now is resourcing the three fantastic people that we have in those positions.

I’m working much, much harder than I ever did in government, or private enterprise for that matter ‒maybe except for crab fishing ‒ but what gets me going now is that we are actually making a measurable difference. And the impact is huge. When I first started, you would say “What is the catchment committee?”. Nobody really had any idea of who we were. And that’s changed a lot. I think it’s because the programs that we’re running are effective and they’re driven by science, and people get excited by that.

My most exciting thing over the last couple of years was when we crowdfunded the purchase of Eungedup Wetlands. That was only possible because of the reputation and the effort that went in before that: people had the confidence to give us money because they knew it was going to be used efficiently and for a good purpose.

Another concept that we’re developing is the establishment of a biorefinery in Denmark, which will use pyrolysis to make biochar for our local agricultural and gardening communities from food organic waste, green waste and silage plastics. For a little catchment group to be pitching a 3-million-dollar, three-and-a-half-year program in collaboration with universities is a big step up from where we were in 2015, when I started, but that’s purely because of who we’ve attracted to WICC.

Keith: What else has led to WICC’s success?

Shaun: The continuity of funding provided by the Department of Water to carry out our core objectives has been a critical factor. We have been able to leverage that funding to develop other programs.

People are another factor. There are so many smart, incredibly talented people in this community. And most of these people want to contribute. They want to make a difference. Some might be at the end of their careers, but they still have a lot of energy to put into making changes. We’re really fortunate that we’ve got a number of them on our board and the contributions are huge. Many others are our wonderful community volunteers who are essential to so much of what WICC achieves.

I think another key reason for WICC’s success is that we’ve given our project officers a lot of freedom. They’re so incredibly passionate and knowledgeable.

Unfortunately, in landcare programs there’s often a high turnover of staff. They’re under-resourced and they’re just treading water until they can find something that’s more secure. And off they go and you lose whatever knowledge was gained. I’ve seen that enough so that’s what I didn’t want to happen with WICC. The way forward is to pay people appropriately, give them ownership of the program, and make sure it works for their work-life balance. When they’ve got everything together ‒ they’ve gone to their kids’ assembly, had breakfast with their friend and fed the cows ‒ then they’ve got four hours to focus on work. You get the best four hours ‒ all the stuff starts flying.

I think the more you learn about the state of the environment, it can be a bit overwhelming. WICC can only plant so many trees. We can only fence off so much ourselves. As a catchment group, I think we would be kidding ourselves if we think we’re going to solve the biodiversity problem for our area, based on what we can do ourselves. This is where social science comes in.

What we need to do is create behavioural change in the community. That’s how we’re going to make environmental change. It’s not going to be WICC physically going in and doing it. It’s us encouraging and helping other people to do it. This thinking has become a big focus of how we design and carry out our programs.

I’m obsessed with efficiency to give value for money. I think the less you handle something to get the objective that you want to accomplish, the better. The best way of doing that is using good social science and the design of good programs. So it’s not about us planting the tree ‒ you want to get other people to plant the trees.

Keith: What’s an example of something WICC is doing to bring about behavioural change?

Shaun: We’ve introduced a black cockatoo conservation program, which we’re launching over the next few years. We’ve run an expression of interest (EoI) with landholders who want to take part in this. Over 90 landholders throughout the catchment area responded and they want to give up some of their land to black cockatoo conservation. We only have funding from the State Government to pick up about 40 of those so I’ve been in a conversation with Lotterywest, who want to jump on board and help us expand the program. So this is exciting.

We currently have a Noongar Ranger team that is picking seed from these properties. Seedlings of this black cockatoo flora are being grown at the Denmark nursery and we’re going to plant about 30 hectares throughout the catchment. To maximise behavioural change across the broader community, we’ll provide a platform for these landholders to tell their stories, inspire others and attest to the positive changes they’re making. We’ll make it infectious so other landholders adopt these practices too.

We’re also putting up 40 nest boxes that will be built by the Men’s Shed. The design comes from Simon Cherriman, the award-winning ornithologist and environmental educator. Simon is coming down as part of the program. He’s not just showing us how to build these boxes, he’s also going into all the primary schools in our area and delivering talks, building a nest box with the kids and shimmying up a tree in the school grounds and putting the nest box in place. Then the kids are going to pick seed with our revegetation officer, propagate that and plant it around the nest box area and that’s all going to be fenced off. So each school is going to have a black cockatoo refuge.

The purpose of that, back to the social science approach, is it’s not just WICC putting up the 40 nest boxes. These kids are going to have what they learn as a legacy. We’re planting the seed in the kids’ heads and it’s going to pay dividends over the next 10-20-30-40 years. That’s where we’ll have our biggest impact.

Keith: What do you think is the future trajectory for WICC’s work?

Shaun: There’s so much work to be done, and we’ve got some grandiose ideas. Rather than apply for short-term government grants, we are going to design our own projects and then find somebody to fund them. I believe you have to keep that optimism. One thing my dad told me really early, and he probably got it from somebody else, he said whether you think you can or whether you think you can’t – either way you’re right. And that really resonated with me and I think about that quite a bit. If you think you can’t do it well then yeah, you’re not going to do it.

I really believe that Gondwana Link serves as an inspiration for a lot of groups. I think it’s about setting those big landscape ideals, and that’s what we need to do. We need to change the trajectory of things at a rate of knots. Government has got to start putting money into the environment. And, looking at the likes of what’s happening with Gondwana Link and what’s possible with a large vision, I think the biggest threat we have is setting our visions too small. We need to move beyond small, short-term projects. Now is the time to think big. If we replicate that large vision approach in other places throughout the State, then I think there’s hope.

This story is largely focused on Pibulmun and Menang country. We respect the deep knowledge Pibulmun and Menang people have of their country and its wildlife. Thanks to Shaun Ossinger, Keith Bradby and the photographers. Editing by Stephen Mattingley, Keith Bradby and Margaret Robertson. Photo editing by Carol Duncan.