The Western Ground Parrot and me: A story about Brenda Newbey and Western Australia’s rarest bird

by Anne Bondin and Brenda Newbey

It is a bird very few of us have ever seen: a parrot which dwells on the ground and is most active around sunrise and sunset. Its call has been likened to the sound of an old-fashioned whistling kettle.

Image: Alan Danks

Critically endangered, with only one known population surviving in the wild, the estimated population of the Western Ground Parrot is less than 150 individuals. Most of us only became aware of its existence when Kyloring, as the Western Ground Parrot is known by the Noongar people, came perilously close to being wiped out by uncontrolled wildfires burning through a huge part of its habitat at Cape Arid National Park and nearby Nuytsland Nature Reserve in 2015 and again in 2019.

Brenda Newbey’s first encounter with the enigmatic parrot took place many decades earlier, but even then it was an extremely rare experience:

“1977 was a big year for me. I began learning how to identify the local birds, joined the Royal Australasian Ornithological Union (RAOU), which is now BirdLife Australia, and met my future husband, botanist and farmer Ken Newbey. Ken told me about a green ground-dwelling parrot he had occasionally glimpsed checking him out while he was crouching down, recording plants in low heathland in Vacant Crown Land north of Fitzgerald River National Park.

First sighting…

“I moved to Ken’s farm in Ongerup early in 1978. In spring 1979, while we were driving in the Crown Land north of Fitzgerald River National Park, along Hamersley Drive (now Old Hamersley Drive), he mentioned that we were close to where he had experienced one of those interesting parrot sightings. We proceeded slowly and, incredibly, within a minute or two we noticed a green parrot on the side of the road. We stopped. As I raised my binoculars the bird began to walk onto the track. It stopped about a third of the way across, side-on to us and only about ten metres ahead. Hoping the bird might pause for long enough, I opened my copy of Peter Slater’s ‘A Field Guide to Australian Birds: Non-passerines’ searching for the page with a small coloured illustration of ground parrots and night parrots. Miraculously, the bird waited patiently while we found the page and checked feature by feature ‒ the plumage colours and design, the long tail, red above the beak ‒ until we were absolutely certain that it was an adult ground parrot.

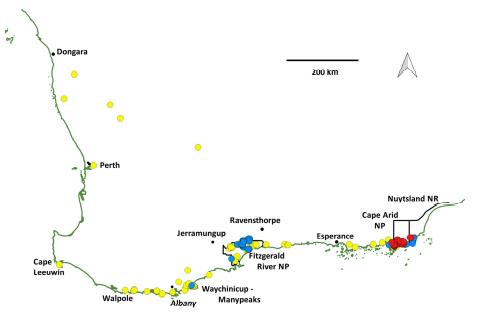

By the 1970s ground parrots had already been seriously impacted by land clearing and the introduction of predators such as foxes and feral cats. Historically the birds were found in heathland all the way from Dongara, north of Perth to Israelite Bay, east of Esperance. However, the fact that no nests had been found since 1913 did not bode well. Brenda and Ken soon realised that ground parrots were very scarce in WA.

Worryingly, they discovered that three of the very few locations where there had been relatively recent records of the parrots had since been cleared and turned into farmland. Late in 1982 the threat of land being ‘opening-up’ for agriculture in the Vacant Crown Land north of the Fitzgerald River National Park became a further danger to the parrot.

A serious threat…

“It was likely that the ground parrot population in the land now designated for agriculture could be important for the survival of the species. Yet the Minister for Lands was very determined to go ahead with the plan. I approached the chairman of the Western Australian branch of the RAOU (now BirdLife Australia) to voice concern about the imminent loss of this known ground parrot habitat. He was more familiar with the habitat of the Eastern Ground Parrot, which in Victoria was mostly swampy sedgelands. In fact, at that time, a very common name for the ground parrot was swamp parrot. This also fitted with the flat swampy country near Denmark where Whitlock had found two nests back in 1912 and 1913. The chairman, a professional ornithologist, questioned whether the birds actually lived in the harsher, drier, and further inland heath of the north Fitzgerald – perhaps they just came there seasonally. There were by now a few records but they had been in July, October and December (winter, spring and summer). If birds could be found there in autumn then it was highly likely that they were resident.“

It was essential to establish that the birds used the habitat throughout the year. However, detecting Western Ground Parrots is not easy. The birds spend most of the day in or under dense shrubs close to the ground. Occasionally, when disturbed, they take just a low short flight and are therefore very difficult to see. Brenda and Ken had read that ground parrots could also be detected by their call.

Image: Brent Barrett / DBCA

How to survey?

“We hadn’t heard their call before. When we found out that Richard and Pat Jordan were conducting ground parrot surveys at Barren Grounds Observatory in New South Wales we made a request for help. Richard sent a short tape with calls of both adult birds (distant and with wind interference) and chicks and he said to listen from sundown to half an hour afterwards.

“In the summer of 1982/83 we made a few unsuccessful attempts to hear ground parrots in the north Fitzgerald. It became clear that the quite similar call of the Tawny-crowned Honeyeater would pose a challenge in aural surveys of ground parrots. However, a breakthrough occurred on 28 February 1983 when, with Keith Bradby, Ken and I saw a ground parrot feeding on an Ouch Bush (Daviesia pachyphylla) at the edge of Drummond Track in the Vacant Crown Land north of the Fitzgerald River National Park.

Spines are scattered on the ground after a ground parrot

had fed on the semi-succulent leaves of this plant.

Image: Brenda Newbey

Image: Brenda Newbey

“This was the first feeding record for the ground parrot in Western Australia and it provided two valuable clues: where to conduct a listening survey, and one type of feeding sign that may help find other sites.

Saved by chocolate…

“On 12 May 1983, as autumn only had a couple of weeks to run, I drove out to spend the night alone, close to the site where the feeding record had been made. That evening there was a cold strong wind and I heard very few bird calls at all as I listened from sunset for 33 minutes. I got into the vehicle, disappointed, but very relieved to escape the bitter wind. I remembered the bar of chocolate I had brought, so I reached for it and broke a piece off. My cold fingers weren’t up to the task, and the piece fell on the floor. To find it, I got out of the car – and that was when I heard a very clear ground parrot call. It was almost dark, two or three stars were out, and it was around 40 minutes after sunset.

Audio file supplied by Friends of the Western Ground Parrot

“Next morning, three clear ascending calls were heard from a similar direction – at 6.05, 6.10 and 6.13. There were intermittent showers and it was too cloudy to see exactly when sunrise occurred but it was about 6.45.

“From this record, we learned that the timing of ground parrot calls in Western Australia was different from the Eastern Ground Parrot in relation to sunrise and sunset, and the habitat too was different. Perhaps our ground parrots were a similar but separate species?

“Now I was able to alert the RAOU WA that ground parrots were year-round residents in the north Fitzgerald. The organisation sprang into action. Several members participated in surveys in the Drummond Track area and Doug Watkins, a scientist and a skilled birdwatcher, was employed to determine where ground parrots still occurred in WA and to attempt an estimate of the number of calling birds when they were heard.

Image: Brenda Newbey

“This was incredibly timely, as there had just been a change of government in Western Australia. However, while a moratorium on other land releases was announced, the new government decided that the plan to open up the Vacant Crown Land of the north Fitzgerald for agriculture was to go ahead.

Roads had been built to access the proposed farms which were now surveyed and pegged. One of the roads was very near the main Drummond Track ground parrot site, and one of the farms was within the main Hamersley Road ground parrot site. Before Doug Watkins’ work could begin, the date for the allocation of land to farm development had been set. There would be no time for the survey.

“However, as a result of lobbying and the publicity that a small group of us stirred up, the new Minister of Lands deferred the land release, pending the Doug Watkins fieldwork and report on the status of the ground parrot in Western Australia. The deferral became effective less than 24 hours before the time set for the land release!

The Watkins report of 1985 showed that ground parrots were no longer present in most of the locations in which they had been recorded in the past. Ground parrots were recorded in only three locations: Cape Arid National Park (one site), Fitzgerald River National Park (one site), and Vacant Crown Land north of the Fitzgerald River National Park (five sites). Between surveying and writing up, half the Cape Arid site was burnt.”

Fitzgerald River National Park. Image: Sarah Comer / DBCA

After a long delay, and much uncertainty, Fitzgerald River National Park was extended northward in 1989 to include the land where the Western Ground Parrots had been found. This was a great achievement, with the effort to save the Western Ground Parrot also protecting an important habitat for many other species.

Brenda’s involvement with one of the world’s rarest parrots did not end there. In 1996, she became one of the inaugural members of the Recovery Team for the Western Ground Parrot which is now known as the South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Team. She was a member for 25 years, retiring in 2021.

In the late 1990s, Brenda began to rally volunteers to help search for the rare and elusive parrots and in 2003 she became one of the founding members of the Friends of the Western Ground Parrot. By that time it had become obvious that the already low Western Ground Parrot numbers had declined even further.

This Albany-based organisation, which Brenda chaired for many years, is now a registered charity. Over the years, hundreds of thousands of dollars have been raised to support recovery actions for the Western Ground Parrot. The group also lobbies state and federal governments for funding to support conservation work needed to bring the birds back from the brink of extinction.

Brenda’s persistence had raised the profile of the parrot sufficiently so that further study on the habitat requirements and distribution of the ground parrot was undertaken under the auspices of what is now the WA Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), with assistance from the RAOU and many other organisations and individual volunteers.

Sadly, the birds now seem to have disappeared from the Fitzgerald area. Despite extensive search efforts, they have not been recorded anywhere in the national park since 2012.

To help raise awareness about the parrot, the Friends teamed up with filmmaker Jennene Riggs who produced the documentary “Secrets at Sunrise”. The feature-length film released in 2017 tells the story of the Western Ground Parrot and the people trying to save it from extinction.

Watch the “Secrets of Sunrise” trailer…

With less than 150 Western Ground Parrots surviving today, the situation may seem dire, but it is not hopeless. Provided that adequate funding is available for the recovery actions, there is no reason why we should lose this unique parrot.

New methods of detecting the parrots have become available through modern technology. Automated recording units can be set up in the field for months to monitor the last wild population, and perhaps to discover birds in areas where they have not been seen before.

Control of feral predators has become more sophisticated with a variety of baits now available. The Parks and Wildlife Service of WA carries out regular baiting to protect the birds in the wild.

With a changing and drying climate in the southwestern part of WA, wildfires started by lightning strikes have become much more common and have resulted in large losses of habitat at Cape Arid National Park and the adjoining Nuytsland Nature Reserve, the home of the only known wild population.

However, attempts are underway to establish a second wild population east of Albany. Following a successful trial translocation of seven birds in April 2021, a second group of ground parrots were translocated to the same area during the winter of 2022. At the time of the second translocation there was no evidence of breeding taking place amongst the initial group of translocated birds. Watch the segment of ABC’s Landline called “Parrots in Peril” to follow the efforts of the team involved in the translocation.

Meanwhile at Perth Zoo, a small, captive population may be able to augment the population in the wild if the parrots can be bred successfully in captivity.

For now, even if you may never see a Western Ground Parrot in the wild, Kyloring’s song can continue to be heard after sunset or before sunrise at some heathlands on the South Coast.

Further reading:

Friends of the Western Ground Parrot website

Parks and Wildlife “Western Ground Parrot” website

Creating a Future for the Western Ground Parrot

ABC Open – Dave Taylor, Friend of the Western Ground Parrot

‘Saving Kyloring’ by Riggs Australia (video)

Translocation of Western Ground Parrots – DBCA media release (11/06/21)

Translocation of more Western Ground Parrots – DBCA media release (27/07/2022)

Sincere thanks to Brenda Newbey, Anne Bondin of the Albany Bird Group and the numerous photographers. The title photo of a Western Ground Parrot was taken by Alan Danks. The story was published in 2022.