Yarning about fire

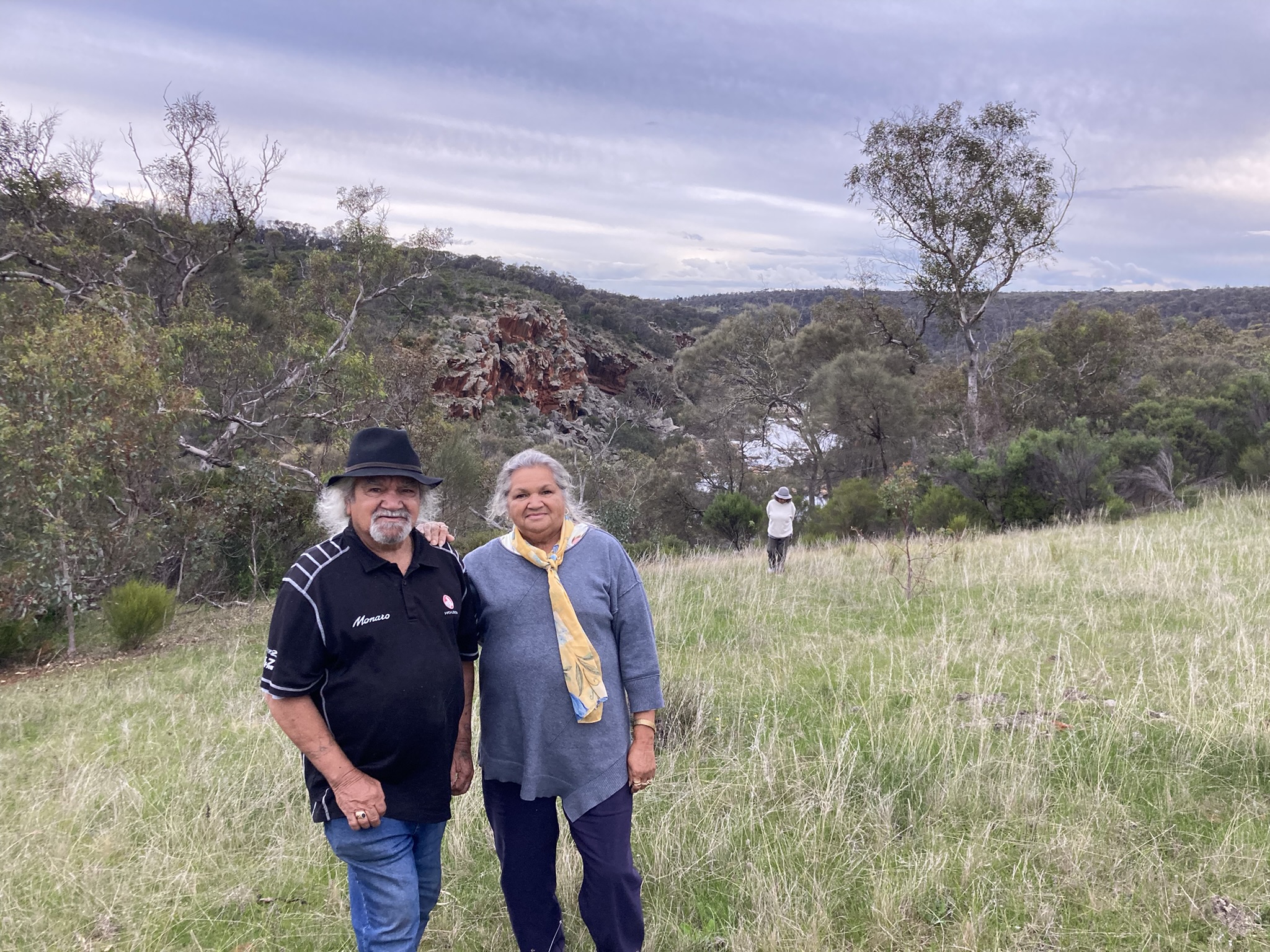

Noongar Elders Aden Eades and Elizabeth Woods, and PhD student Ursula Rodrigues, are part of a team working on a cultural burning collaboration on Country between the Fitzgerald River and the Stirling Range (Koi Kyeunu-ruff) national parks.

As part of this project, they have been yarning about fire, its impacts on Country and its role in culture, as well as conducting Elder-led burns to revitalise Goreng Noongar fire knowledge and stewardship. Their story is a joyful portrayal of Noongar and wadjella people working, laughing and learning together as they undertake an important fire management study.

Aboriginal people are warned that this story contains the names of deceased persons.

Siblings Uncle Aden and Aunty Elizabeth (Eliza) are yarning with Ursula from UWA Albany about the Eades-Penny family, their fire knowledge and the importance of fire in Noongar life.

Aden: Before we talk about fire, we have to acknowledge our old people and the Elders that taught us so much. On our dad’s side, Grandfather Eades was a good old teacher. His father was a wadjella (white person) and his mother was Lucy Coyne, an Albany Noongar. He picked up a lot of cultural knowledge from her and was a very knowledgeable bushman.

Grandfather Eades married our grandmother, Granny Ettie, who was an Arthur River Noongar. They had two daughters and ten sons — our dad was Fred — and they lived Noongar lives across the Great Southern and Southwest. Granny Ettie spoke language and knew all the culture and she handed that onto her kids. The boys all went into the bush; they were all good bushmen.

Eliza: Our mum’s dad is Grandfather Chris Penny. Through his mother, old Maggie Starlight-Piggot, he’s got connection to Denmark and further west, even though he was born in Kojonup. The family lived all over the Great Southern, finding work. They were one of the first families to go to the Jakitup school, out from Gnowangerup, where Pa Chris learnt to read and write. Pa was always a worker ‒ he was a shearer and builder; he helped build quite a few of the cottages on the United Aborigines Mission at Gnowangerup. Pa married our grandmother, Granny Agnes Woods, in Gnowangerup. They had thirteen children ‒ our mum, Ayplin, was their eldest daughter.

Pa Chris and Granny Ag were very family orientated. Their principles and values rubbed off on us — we always care for each other. Granny Ag was a real matriarch and she made sure we were looked after even through the toughest times. We went bush with her and learnt about bush tucker. She taught us the importance of culture.

We’ve been really privileged to have such people we can look up to with a lot of pride, love, and respect and who handed over the baton to us. Now we’re talking about handing the baton over to the next generation. Our yarn today comes back to people, because without people who are our teachers, we wouldn’t be able to do what we’re doing.

There’s so much we can talk about, but at the end of the day, I think it is about going back and respecting our cultural values, cultural practice, and what’s been instilled in us by our Elders.

We often have to work in a wadjella way and that’s important now because we live in a different era, a different time and place. But we hope our stories will keep going too, and that’s why I think it’s important for Aden and me to make some kind of contribution ‒ we’re the talkers of our experiences, we’re the knowledge sharers for our family. We respect other families’ experiences, but this yarn is from our Eades-Penny experience.

Aden: Kaarl (fire) was always part of our life. I was born in 1939 but didn’t live in a house until 1970. I was living in the bush on the reserve in Ongerup and had five kids by then. We had a good life in camps and the kaarl made sure we were alright. We had all the comforts thanks to the fire.

When we were young, our family ‒ Grandfather Eades and his sons ‒ worked on farms during the land clearing years, burning up and cutting down and dealing with fire all the time. We learnt the cultural side of fire from a very young age from my other grandfather, Pa Chris Penny, and Grandmother Agnes. We didn’t mess around with fire; you don’t do that. That’s wiirnitch. That’s bad to do that.

As we grew, we were taught about patch burning. They’d burn up an area something like the small Elder-led burns we have been doing as part of our fire project, about 500 m2. They might do several patches and leave space between them, but they wouldn’t burn it all. They would light each patch and put it out. I remember they used to burn a fire break, instead of raking like we do today. Burning was mainly done for next year’s meat supply. The fire brought up new growth and fresh grass which yonga (kangaroo) and other animals liked to eat. The old people would come back to hunt in the burnt patch the following season.

Eliza: We’d also burn for bushfoods, to encourage regrowth of all the bulbs and tubers, and our little runners with their fruit, like kurrup and kumuk (Billardiera spp.).

Aden spoke about his experience growing up with Grandfather Eades, but I always think about my experience of seeing fire. In mallee country, root picking and burning up were important when the farms were being cleared, but prior to that, fire was the centre of our camp life. It was our kitchen, our main place of gathering. The campfire was our classroom, that’s where we learnt about culture, the importance of fire, the bush, everything. We observed our parents and grandparents carrying on cultural practice around that fire and securing their bush camp by cleaning up the undergrowth and grass and sweeping it around. They took great pride in their camps.

Some younger Noongar people might think that this knowledge has gone but if we want to keep our culture and cultural practices, family values and beliefs, we need to continue it on and acknowledge that it is still there. These yarns identify who we are. Our language, our songs, our song lines, all connect to place. They’re all linked like a chain and it comes full circle back to the kaarl (fire).

Ursula: Through the time I have spent with the Elders on Country yarning about fire, they have taught me that there is no distinction between campfires, which are the social centre of life, and small controlled burns used to clean up and care for Country. The connection to fire through Noongar culture and spirituality is clear to me every time we are on Country together, like the warmth of sitting around a campfire with family and friends.

Country is the basis of life in Noongar culture. Permits and restrictions can prevent Noongar people from fulfilling their cultural obligations to access and care for Country.

Eliza and Aden: Now there are so many restrictions on fire. As Aboriginal people, we feel that we must ask permission all the time. As colonisation took over, we were either fenced in or fenced out, mostly fenced out. In our hearts, we feel like we shouldn’t have to ask permission to enter and care for our sites because we are connected to this country. Our grandparents and great grandparents walked and lived and hunted on these areas that we live in. So, there is always that question, why do we have to ask permission?

Our Elders knew all about the safety of fire. I don’t think in history a Noongar has ever let a fire get out of hand. We are aware that fire is danger and we’ve seen the damage done to properties and people’s lives by bushfires today.

When we were young, our lives were very restricted and through discrimination we weren’t allowed to do a lot of things. Talking about fire permits takes me back to when Noongar people had to ask for a permit just to go into town. Even our old dad who was a returned soldier had to have a permit for that. Those kinds of things still have an impact on us. It impacts how Noongar people can accept or work with non-Aboriginal people. For me, non-Aboriginal people have got to win up that trust, first. Stand with us and look through our Noongar lens and see where we are coming from.

Wadjellas need to understand how important Boodja (land) is to Noongars. Noongars observed the Boodja. They’d see tracks from karda (goanna) or yourn (bobtail); or maybe a well-used yonga pad; or they’d see the hole in the ground where the old ninghan (echidna) went; or they might see possum scratches on a tree. Noongars always had six seasons. They knew what resources they could get when and where. For example, quandongs are only out during summer, so that’s when they’d go looking. Now we have weather like never before.

With burning today, Elders need to decide where it happens. We need to look at what plants and animals are in the area first. Once you know what’s growing there before a fire, you know what you’ve got to look for next year, and you can identify if there’s any new plants that come up after the burn. If the government or others are planning burns somewhere close to the old Native Reserves, or Country where Noongars lived, or a heritage site, it needs to be communicated with Elders. There could be a sacred place there or important food and medicine that could be damaged by a fire. In our burns, we protect life in general, but we need to see if there’s anything of significance there that needs special care. Now that we have been fenced out for a long time, we need to re-connect to knowing some places again.

We also need to identify the different vegetation that’s going to be burnt, because that demonstrates the speed of fire, how it can travel. At a recent burn in a grassy area, it was quite windy, and the fire travelled very fast compared to our burn the day before under gum trees. But we had a bit of rain early that morning which helped because under the dry grass was damp, so the weather does play a part.

Noongars used to study the clouds and the wind to determine the right weather for burning — we still do that now. With technology we can use that to help us juggle and judge what day will be good.

Weather has to do with the safety of animals too. If you let a fire go and all the animals get boxed in and burnt, that’s no good. The very reason why we’re burning is to make sure the populations grow, for bush tucker, but also to look after animal and bird life and plants. We burn in the right season and control it to protect those things. It’s not a big burn, it’s not a fast burn, it’s a slow burn, to let the animals escape.

As part of the collaborative project, Elders have been leading small fires on conservation properties in the Fitz-Stirling region to revitalise Country and fire practice.

Eliza: We recently did some burning in collaboration with wadjella organisations. Because we led the burns, we felt that we were in our own environment. We felt ownership and stronger connection to Country because we’re caring for it as we would care for a baby, nurturing it.

Aden: During these burns, I felt like I was living part of my old life when I was young, doing the same sorts of things from back in those days. When I get out in the bush, I’m right, I’m absolutely in my own environment.

Eliza: My observation was that all the wadjellas working with us showed a lot of respect. There was lots of communication and we were right in the action. I was so happy, true! The younger Noongar caretakers (rangers) also listened to us. We felt that our skills and knowledge were put into practice, and we saw it firsthand. That’s very rewarding and makes me feel like we are being valued.

Aden: Those fellas we had out there are professional people, full of knowledge about fire, and yet they just came right to our level. They were very respectful, and appreciative of our input. We were working together; they fitted right in ‒ it was just like all Noongars together.

Eliza: The burns were quite moving. It really does take you back. Even though the methods are a little bit different, the principles and the purpose behind it are the same. We don’t burn because we want to have fun or make smoke. There must be a purpose behind everything you do in the bush. We don’t just go out there so that someone can get a certificate saying they dealt with fire. It’s more than that.

There’s an emotion that comes in too. We’re excited that we’re able to do this now, but there’s sadness too because for our people back then, before big shops, the bush was their shop. And they got fenced in or fenced out and couldn’t go to a particular place where there was good hunting or good bush tucker. We’ve experienced that exclusion too, but now we are on the road to having a voice. Back then, they didn’t have a voice. So that’s where I think this project goes deeper than just fire. It’s about dealing with past hurts.

Uncle Aden, Aunty Eliza and Ursula are part of a team of Elders and researchers who have been working together on the ‘Walking Together’ project at UWA Albany for the last four years, recording Noongar family histories while learning about Country.

Eliza: We’ve been working alongside scientists to record the changes in Country after our burns. We are measuring the food and medicine plants that come back, as well as the weeds and other changes like the amount of dead leaves, twigs and branches. We’re working in partnership with Noongar and wadjella ways of looking after Country. It is a two-way learning curve. Like recently at Nowanup, Ursula had these big measuring tapes, and I was thinking, “What’s this woman here doing? I’ve never seen that before.” So, it was a learning curve for us too, just like the students learn from what we share. If we’re going to work in partnership, there has to be Noongar and wadjella ways involved.

Ursula: It’s so rewarding to share ways of listening to Boodja (land) with Elders and to learn how our knowledges can work together for our common goal of caring for Country. I share my scientific knowledge and skills in quantifying and recording changes in the vegetation after a burn and the Elders share their ways of seeing the bush. There is always something to learn, mistakes to make, and usually I’m the laughingstock!

Eliza: As I look back over the last couple of years that we’ve been working together, I feel that I have been so blessed to be able to share some of my life’s journey, family history and stories of places and people, and to learn some new knowledge about connections our family has in the Great Southern.

Aden: The knowledge has been lying dormant. When we revisit places where we grew up, it’s like turning a page in a book and seeing scenes from our childhood. But now, when we reflect on those memories, we’ve got the freedom to reconnect to the knowledge that our Elders gave us.

Eliza: We’ve got the opportunity now with technology to record our stories. It’s more than just research to us. We’re not going to end up with a Doctorate, but we’ve already got that because we were born with our knowledge and our culture. We get to record our stories and comments; that’s going to be there for a lifetime, for our children and grannies. I feel safe that our things are in good hands.

Aden: Some of the researchers have become like family. I’ve enjoyed the time I’ve been involved with the university, and I always look forward to the next trip. We have a bit of fun along the way, a few laughs, but that’s how friendship goes. It’s more than friendship, they feel like family.

Eliza: Spending time on Country is so important. It gives us time out from our daily routine. Everything’s left in town, and we can recharge our physical batteries. It is so nice to sit around and yarn with other Elders and families. On a recent trip, we sat around the fire, having damper as if we were home, having the best time.

Ursula: Working together means establishing reciprocal relationships. As researchers we have obligations to Noongar colleagues to look after the knowledge entrusted to us and to do our best to answer our shared questions with the skills we have. We also have obligations to work more broadly towards institutions, communities and towns that are more embracing of everybody.

Eliza: Wadjellas have been a part of our lives for over 200 years. If we work side by side with them, in any field, it must be a two-way relationship. It must come from a place of respect for each other and for what’s happened up to today. We can’t change the past, but we can make the future better by communication. Our purpose is to record and create knowledge that will be helpful for our Noongar kids, for wadjellas, for everyone, to create a better future for all people and for Country. Yarning about kaarl, fire, is a really powerful way to do that.

THANKS to Aden Eades, Eliza Woods and Ursula Rodrigues; the photographers; Alison Lullfitz, Marg Robertson and Keith Bradby for editorial input; and Carol Duncan for photo editing and webpage development. Thanks also to Uncle Eugene Eades, Stephen Hopper and Bush Heritage Australia.

Special thanks to all Noongar collaborators and families involved in our cultural fire project. This project acknowledges the funding contribution of the Commonwealth Government and support from the WA State Emergency Management Committee. This work is a collaboration with UWA Albany Walking Together Project, funded by South Coast Natural Resource Management and supported by Lotterywest.

This story is also available online in the November 2023 edition of the Southerly Magazine.

FURTHER READING

- “Karla Wongi.” Kelly, G. (1999): https://library.dbca.wa.gov.au/static/Journals/080052/080052-14.026.pdf

- Rodrigues, U., Lullfitz, A., Coyne, L. et al. Indigenous Knowledge, Aspiration, and Potential Application in Contemporary Fire Mitigation in Southwest Australia. Hum Ecol 50, 963–980 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-022-00359-9

- Lullfitz et al 2022. “We can write novels of the memories made here”. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/we-can-write-novels-of-memories-made-here-elder-led-land-restoration-is-about-rebuilding-love-187855

- “Indigenous Aspirations and Capacity for Bushfire Response”. NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub. (2021): www.nespthreatenedspecies.edu.au/projects/indigenous-aspirations-and-capacity-for-bushfire-response

- “Cultural and contemporary fire practices”. DFES. (2021): https://www.dfes.wa.gov.au/site/documents/Cultural-and-Contemporary-Fire-Practices.pdf

- “Guide for developing a fire management plan”. Firesticks. (2020): www.firesticks.org.au/category/resources/planning-tools/

- CASE STUDY: Local Government and Southern Noongar people walking together in fire management: Southern Noongar Kaarl.

- “A Natural Blackfella thing, hazard reduction, or both?” Knapp, L., Lullfitz, A., Rodrigues, U. (2021): https://vimeo.com/channels/fabforum/576642908

- “Kaarl wobbitch wer worra” Knapp, L. & Rodrigues, U. (2023) https://vimeo.com/channels/fireandairforum/855898558

- “Karla Wangkiny – Fire talk with Lynette Knapp.” (2021): https://youtu.be/7aX3s-aGGIA

- “Auntie Carol’s Story.” Petersen, C. and Burton, N.M. (2021). Cultural Burning in Southern Australia, BNHCRC, Melbourne: www.bnhcrc.com.au/resources/poster/8218

- Underwood, J. Talks tackling the burning issues on Country. Southerly Magazine 47, 18-22 (2022). Also published in Gondwana Link’s Heartland Journeys website as ‘Giving fire back to Goreng Country’