Balijup farm: family, people and nature working together

For many decades, Balijup farm near Tenterden has been a shining example of landcare in action. Its lakes continue to support waterbirds like swans and hooded plover, its woodlands remain dotted with mature trees whose hollows are home to a range of wildlife. But over time, changes across the wider landscape have rippled through Balijup, with various wildlife species disappearing from the farm. In recent years an enthusiastic collaboration between the Hordacre siblings Alan, Richard and Anne, who own the farm, and the conservation group Green Skills has brought back the quenda and enabled other species like brush-tailed possums and brush-tailed phascogale to flourish.

Alan Hordacre and Green Skills’ Basil Schur give a heart-warming account of family, people and nature working together.

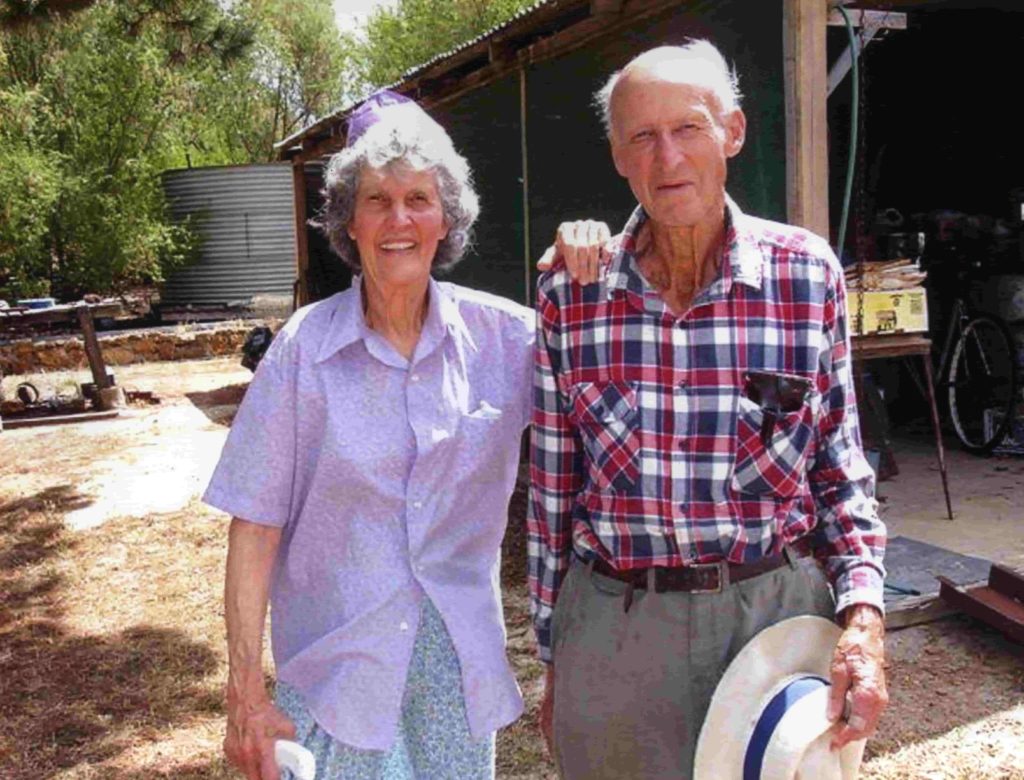

ALAN: I feel strongly connected to Balijup. Its 921 hectares have been in the Hordacre family since 1923. My Dad and Mum, Tom and Nancy, took over the then-bush block from Dad’s parents in the 1950s, so Anne, Richard and I grew up here.

Our parents were do-it-yourself people — they built everything on the place, and always had a veggie patch, orchard, preserves and home butchered meat. Dad started building the house in the late 50s after he and Mum, who was a teacher, nurse and midwife, were married. Typical of the era, it was extended as kids were born and never really finished, but it was warm, comfortable and a place of games and learning. The kettle was always on. City cousins, and now their kids, visited Balijup, extending the family connection.

There weren’t a lot of dollars, as was the norm back then, but there was plenty of tucker, interesting activities, and love. Both Dad and Mum had a great love of the nature on Balijup and passed that on to us kids. They never objected to us planting trees on land that had been cleared through hard work. Many a time Dad said he would like to put a big fence around the place and create a national park. We have now gone a little way towards creating that legacy.

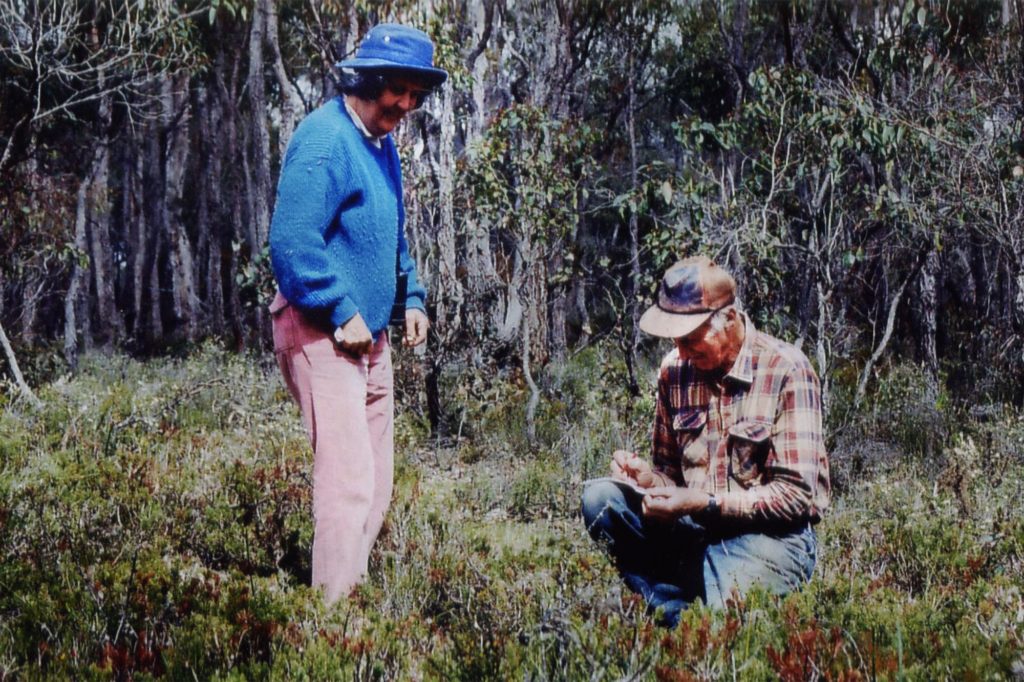

Dad spent a lot of his later years collecting native seed for sale to Peter Luscombe’s Nindethana Seed business near Albany. He enjoyed his time out in the bush, identifying plants that he could come back to later when the seeds were ready to be harvested. He also posted plant samples to Nindethana and the WA Herbarium, asking for help with their identification.

Dad joined the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union and over many years produced an extensive bird survey of Balijup. His list of 85 species, which included the seasonal birds, was very helpful when Sylvia Leighton wrote the farm’s ‘Land for Wildlife’ report in 2012.

Mum also had a strong sense of place here at Balijup. My sister Anne recalls Mum had a great love of walking around in the evening and just looking at the different sights and seeing the beauty of what the farm was. She had the ultimate choice in where the house would be located. Dad offered her two sites. One was where she would see the sunset every night, and the other one had a view to the Stirling Range (Koi Kyeunu-ruff) during the day — that’s the one she chose.

They lived here until 2010, then moved into care in Albany and passed away soon after. Dad always said ‘you can drag me out in my boots’. A statement I reflect on with some regret, but also appreciation that that was not required.

Going back, our grandfather Les Hordacre took up the farm as a bush block in 1923 — 100 years ago. He seasonally ran up to 500 sheep through the bush. The first clearing using bulldozers occurred in the 1950s, though there was a small area of ringbarking prior to that.

Dad had the attitude that he didn’t want to clear the place from fence to fence. He wanted to enjoy nature on his own patch — he liked having trees in the landscape, and they were shade for the sheep. He saw a way that he could bring up a family and have a comfortable life without having to have debt or clear the whole property. But he was also a keen farmer, especially as a young man. He was up with the latest technology of the time. And Mum, being a city girl from a bushy suburb beside the Swan River, always related strongly to nature and probably had a fair bit of influence in the lack of bulldozing to clear the bush here.

The farm name Balijup means place of many lakes in Noongar language. It was part of a prehistoric river system. Over millions of years, the river system filled with sediment and dried up, so each lake or swamp is now a totally closed little catchment.

The original survey document for this farm, which was done in 1920, made quite detailed reference to the vegetation and the natural environment — there were salt lakes, paperbark salt swamps and reed swamps. These hand-written descriptions on the original survey very much fit what I experienced as a kid in the 1960s. The salt lakes were just that, the paperbark salt swamps were brackish, and the reedy swamps were freshwater and full of waterbirds, frogs and snakes.

Some freshwater swamps have been lost, unfortunately, though with protection from grazing they are evolving into useful habitat. But if we cleared the whole farm, all of them would be salty. Simple as that. I have observed that very little clearing is required to affect the salinity of these lakes.

Balijup’s environment is largely protected now — even more protected than it was 20 years ago. That’s involved tree plantations, landcare plantings, and fencing of bush and parkland-cleared areas to exclude grazing and encourage regrowth. Much of the bush hasn’t been grazed for 70 years and is in good condition. Put another way, 670 hectares is made up of bushland, wetlands and the fenced parkland-clearing that is rapidly reverting to bush.

Even with all these measures, there are still some challenges. Things like the high population of kangaroos, wildfire potential, salinity, maintenance tasks, controlling cats, foxes and some small populations of weeds, and how to help wildlife survive the run of all the bush areas and spread elsewhere.

While I like to protect the environment, the reality is you’ve got to have some cash to do that. Otherwise, you’ll be forced to sell the place and then anything can happen. The family has sought to safeguard the bushland by placing a protective covenant over these areas.

I figured that by planting trees that you can derive an income from, you’re killing a couple of birds with one stone, so to speak. You’re reducing the water table and the potential for salt in the lower country; you’re protecting the bush by cutting grazing out of it; and you’re diversifying the income stream. We now have a Forest Products Commission lease for hardwood trees – yate, sugar gum and spotted gum — as well as sandalwood. We’ve also planted some private plantation, including bluegums, and salt-tolerant species for landcare. Bluegums provide the best return and we are looking towards a third harvest from the mid-1980s plantings. I’m a forester and Richard has a tree nursery, so getting trees planted was pretty straightforward. On top of that, with the son of a lifelong friend we share-crop about 120-hectares of the best country.

In 2012, a major new phase began on Balijup when we started working with National Landcare Award winner Basil Schur from Green Skills — I’m sure he’d rather I not mention his impressive accolade! First up, we re-fenced the boundaries between bush and pasture with roo resistant fences to help protect both the bush and crops. Gates are left open to give roos the run of the crop stubble between harvest and seeding. This approach has been reasonably successful.

In about 2013, Basil came up with the bright idea of creating a sanctuary on Balijup for the protection of the smaller wildlife, and to enable re-introductions of some native species. He got a Lotterywest grant to put all that into action, and I gave a hand to get the fence lines in place. We had a well-attended and enjoyable opening of the sanctuary in May 2015, with parliamentarian Tuck Waldron cutting the obligatory ceremonial ribbon at the gate.

BASIL: Inside the gate is 110 hectares of bush that provides a fox and cat proof environment for wildlife. The floppy curve at the top of the high fence means that cats and foxes can’t jump into the sanctuary or climb the fence. We’ve also fitted a skirt of rabbit netting at the bottom of the fence, which prevents animals digging into or out of the sanctuary.

A huge amount has happened at Balijup Sanctuary involving enthusiastic citizen scientists and volunteers, many curious visitors and environmental students, and the extended Hordacre family. It was a particularly special time when 16 quenda (southern brown bandicoots) were brought here from bushland in Albany and released in 2015. After all the monitoring of the quenda population, I can say with confidence that this re-introduction has been successful. They’re important ecosystem engineers, digging for insects, fungi and plant roots, which has benefits like aerating the soil, composting leaf litter, and dispersing seeds and spores. Given the estimate that an individual quenda turns over about four thousand kilograms of soil annually, we were very keen to have them back at Balijup, helping to restore a healthy ecosystem.

Balijup sanctuary is wandoo-jarrah woodland, with a scattering of mallee species, and it’s pretty intact. Some trees were cut for fence posts in the past, but the understorey is healthy, and we assessed the area as ideal for bringing back some of the animals that were here before. An interesting thing about the wandoo woodland in particular is the occurrence of many habitat trees with hollows, which are essential for many of our native birds and marsupials.

To the delight of the bird watchers involved, endangered Carnaby’s cockatoos have been seen breeding in one of the tree hollows here, which adds to the importance of the area. With the guidance of ecologist Dr Sandra Gilfillan, South Coast NRM has installed five cockatoo nesting tubes high up on trees to ensure there are enough suitable nesting sites.

Co-ordinating this sort of work in the sanctuary has been a major focus for me over the past eight years, but it also gives me the opportunity to experience many wonderful things in nature. Seeing a tiny western pygmy possum during spotlighting last year and observing quenda with pouched young have been some of the memorable times.

Once, when leading a Cranbrook community spotlighting event on a moonless night, with 30 or so people comprising local families and lots of enthusiastic children, I got myself completely and utterly lost within the sanctuary’s woodland. I composed myself and calmly asked some of the adults near me if they happened to have a smart phone with both coverage and Google Earth loaded. Very luckily there was such a person, and by trial and error I was able to navigate from where the blue dot moved, and thus locate the boundary firebreak on the fence line. The rest, as they say, is history.

Managing the area, which includes local populations of brush-tailed phascogale, brush-tailed possums, many bird species, and southern heath monitors (the goanna Varanus rosenbergi), is a long-term program.

Each year, Green Skills co-ordinates a citizen science program in the sanctuary. We invite ecologists and wildlife biologists to work with teams of citizen scientists to lay out fauna traps, set up motion-detecting cameras to monitor wildlife, and do bird and vegetation surveys that help us track how the environment is going in response to the absence of foxes and cats.

These generous contributions extend across our other activities at Balijup, and to the backing of funders and sponsors. Projects like the sanctuary do rely on the support of a wide mix of organisations, like the State NRM Program, the Conservation Council of WA, which has supported the citizen science work, DBCA’s Parks and Wildlife Service, University of WA, and the Gillamii Centre at Cranbrook. Alan checks the sanctuary’s perimeter fence, baits foxes and handles rabbit control, and it’s great to have this strong involvement of the Hordacre family in maintaining the sanctuary and implementing other conservation projects on Balijup.

I feel strongly that this is not just a property where we are restoring the environment, it’s also a place of education. School groups visit, and our citizen science teams include university students doing environmental degrees, as well as TAFE students studying conservation land management. The work at Balijup provides these tertiary students with essential experience in working with wildlife. For me it’s fantastic to have a practical project where we can train the next generation to care for our environment. We also get older volunteers who want to be involved in a social activity that gets them out in the environment.

Another focus of our work in the sanctuary is the carnivorous, arboreal mammal called a brush-tailed phascogale, or wambenger. The Denmark Men’s Shed and Al Hordacre have made nesting boxes for the Balijup wambengers. Feral bees like to set up home in these boxes, which are fixed to trees, so the box design has to deter them. These boxes are monitored for wambenger use and the Mt Barker-Nowanup Ranger team have helped with that.

Bird species can be a good indicator of ecosystem health and we are fortunate to have highly experienced bird watchers who conduct bird surveys inside and outside the sanctuary. This monitoring has highlighted the benefit of a feral-predator free environment for key woodland songbird species such as the western yellow robin and rufous tree creeper.

On Balijup there’s not just the sanctuary with its focus on fauna conservation. The farm also provides a wonderful laboratory for how we can look after wetlands in an agricultural landscape. There are over 12 of these wetlands on the farm, and waterbirds use them. Sometimes flocks of swans and stilts and other waterbirds come in, as well as the migratory shorebirds that come from the northern hemisphere on occasion.

Balijup is part of a bigger story too. It’s located halfway between the Walpole Wilderness national parks and the Stirling Range (Koi Kyenunu-ruff). As such, it is part of the Gondwana Link, a landscape-scale conservation program reconnecting bush all the way from the west coast at Margaret River, across the south coast and up to the Great Western Woodlands around Kalgoorlie. So here in this section between the forest and the Stirlings, lies Balijup. With its extensive areas of bush and wetlands, it’s an ideal property for showcasing our work in ecological restoration.

One important resident, or non-migratory, species at the Balijup wetlands is the hooded plover. It’s a shore nesting bird that’s very susceptible to predation by foxes, as well as agricultural impacts. So the presence of hooded plovers on Balijup is one of the reasons why it’s such a special property within the Gondwana Link.

ALAN: This connection with Gondwana Link was reflected in a Balijup-inspired art exhibition called ‘Living Gondwana: A Sense of Place’. Being part of the opening night at the Butter Factory Studios was fantastic. As an aspiring artist who never had the time, Mum would have got a real buzz out of the occasion too. There were prints, sculptures, paintings, creative photography, and fabrics by Noongar and non-Indigenous artists who had spent time at the farm, in the bush and visiting the wetlands. These eco-art retreats on Balijup are another whole dimension that Basil, Green Skills and artist Nikki Green bring to the table.

I guess the main thing I’ve got out of all this activity is that I understand, more than ever, that we’ve got a valuable natural environment here on Balijup that we need to look after, and there’s so much more to learn about it.

I’d actually like to see the sanctuary extended to the full width of the back of our farm, which would be about 500 hectares. Some wetlands would be included in this larger fox and cat free area to help the waterbirds with their breeding success.

After all the landcare effort that’s already gone on here, in a few years’ time it’ll be really interesting to see the diversity coming back to the wetland areas and fenced bush — you can already see it sneaking in slowly. With lots of diversity nearby, nature can just do its own thing — we don’t have to spend a fortune to regenerate it back to a functioning ecosystem.

It’s an ecosystem with people in it as well. That is one of the great aspects of working and engaging with Green Skills and the wider circle of supporters and volunteers.

There’s another dimension to human connection with this place. After Mum passed, a Forest Products Commission contractor stayed at the house for a little while and reckoned Mum was still there at the window, looking towards the Stirlings. He just felt a presence there which, you know — obviously it was her spot. So yes, in lots of ways we feel that Mum and Dad haven’t really left; we can feel them around the place.

I think a big part of that is the times we’ve had here as a family. My sister Anne’s recollection is a beauty because it combines the bush and family. She says “One of my best memories of being in the bush on Balijup was the ‘Olympic Games’. It was in the 1980s and Dad was doing a little bit of burning off and we actually had a torch relay through the bush with my three kids! So yes, we made our own fun and created really good memories.”

My brother Richard, who lives near the west coast, also has some pretty heartfelt thoughts about Balijup: “There’s something about it, I don’t know if it’s spiritual or in my head. Whatever it is, it’s a great feeling to come back here and pay a visit, especially to the bush. It’s very special. It’s special to me and special to all of us, I think. And I’m sure Dad would be over the moon to see what’s happening with the sanctuary and preservation of the existing bushland. He probably didn’t start out that way when he first settled here, but I think he became attached to it quite strongly. Both Mum and Dad would be quite chuffed to see how it’s all turning out. Hopefully, it’ll continue into the future and the whole community will benefit more and more from it.”

This last point of Richard’s is on my mind too: none of us Hordacre kids are getting any younger, so how do we maintain the legacy and manage the succession to safeguard Balijup’s bush, wetlands and wildlife in the long-term?

THANKS to Alan, Richard and Anne Hordacre, Basil Schur of Green Skills, the photographers, and Frank Rijavec for an original recording. Editing by Margaret Robertson, Keith Bradby and Stephen Mattingley. Photo editing by Carol Duncan. This story was published in the September 2023 edition of the Southerly Magazine, which is available online.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Visit Green Skills’ website for a rich collection of Balijup citizen science and fauna monitoring reports

The Threatened Species Recovery Hub has produced a fact sheet about the role of quenda in reducing fuel loads

Find out about egg-laying and other behaviours of Rosenberg’s monitor – Wikipedia

Listen to an audio story about Balijup, featuring the voices of Alan Hordacre, Basil Schur, and field ecologist Joe Porter

Green Skills’ short video Balijup: A jewel in the Gondwana Link is available here

This Green Skills’ video about Balijup includes drone footage of the sanctuary: ‘Balijup farm and ecosanctuary from above‘