-

Toilets Available

-

Picnic Areas

-

Mobile Reception (Telstra)

-

Camping Allowed

-

No Pets Allowed

Featured in journeys:

Cranbrook Lakes loop

Overview

Nunijup is said to mean “place of many snakes” – a descriptive name back when this was a special meeting place for the Kaneang people of the Noongar nation. In those days, Nunijup was a wetland covered in thick stands of rushes which provided cover for tiger snakes.

Early settlers dug wells here for stockmen droving stock through the district. In 1958 the Nunijup Progress Association was formed, a group still active today. Rushes that remained were cleared from the lake, and water diverted from the Kent River headlands to keep water levels in the lake high. Now Nunijup is a body of mostly open water and a treasured local recreation spot.

Until the 1960s the lake was a fresh wetland that occasionally dried out. Now the lake rarely dries and the water ranges between fresh and slightly saline. More recently, lake levels have been lower due to the decline in rainfall experienced across south-western Australia as well as a reduction in the flow of water from the Kent River.

The ways in which the lake has changed – in size and water level, in the loss of rushes and fringing vegetation and increased salinity – are all striking signs of how the surrounding landscape has been impacted by European settlement.

Wetlands like Nunijup still hold important nature conservation values. They are now reverse islands in a sea of farmland – important refuges of native vegetation and natural habitat. As a permanent lake, Nunijup is also a recreational refuge for the local community.

Water quality here is often better than other wetlands in the area, so the lake is especially important for large numbers of shorebirds and waterbirds.

Lake Nunijup is a scenic, peaceful place to visit. It is valued by the local community and visitors, for camping and picnicking, as well as water skiing and swimming when water levels are high enough.

Story of the place

Watch

Lake Nunijup beneath the surface

Credit: Steve and Geraldine Janicke

Noongar Boodja

Freshwater wetlands were important places for Noongar people, including as rich sources of food.Lake Nunijup is known to be an important meeting place for the Kaneang Noongar people.

Signs of the long custodianship of Noongar people are everywhere in the landscape. At Lake Nunijup, a nearby wandoo tree has small cuts in the trunk, made by Noongar people who used these, and the kodj (axe), to climb the tree to capture possums, collect eggs, or to harvest honey from wild beehives, after the arrival of the European honey bee in Western Australia in the 19th Century.

Clearing commences

Clearing of the original vegetation in the catchment of Lake Nunijup began early – around 1860.

By the mid-1960s, around 40% of the area had been cleared and in 1978, when land clearing controls were introduced by the State Government, almost 60% of the catchment had been cleared.

Land clearing controls were introduced here and in a few other south-west river catchments much earlier than in most farming areas, as the clearing and agriculture were turning the main rivers, such as the Kent River, saltier.

Lake Nunijup from above

Image: Kevin Hopkinson

Before clearing, the original deep-rooted perennial vegetation utilised the available groundwater. When removed and replaced with shallow rooted annual pasture and crops that were unable to utilise all the groundwater, the level of the water table rose, bringing to the surface salt stored deep in the soil. Read more about how salinity has impacted Western Australia.

In the Cranbrook / Frankland region, groundwater levels have risen as much as six metres since the land was cleared and the perimeters of most lakes in the region have expanded since the 1960s because of this rising groundwater.

More recently, with the dramatic reduction in rainfall in south-western Australia, there is less recharge of groundwater from rainfall, and so the water table has stopped rising so rapidly.

Increasing salinity

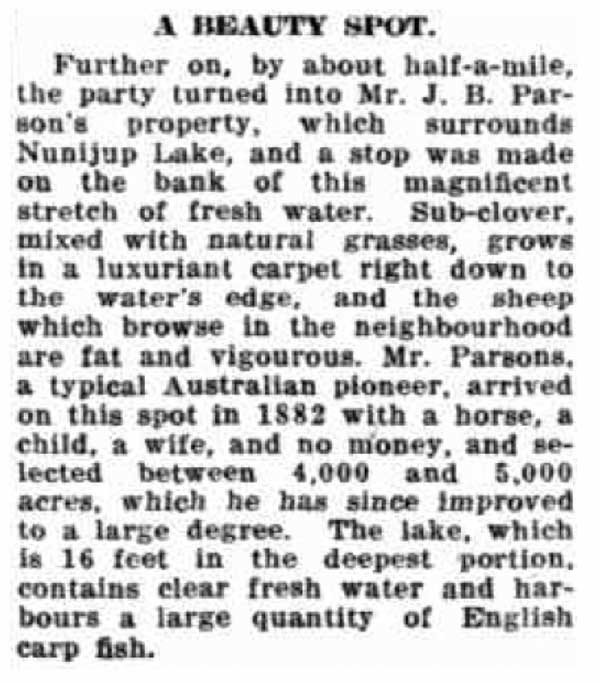

In November 1929, the Minister and Director of Agriculture toured the Cranbrook-Frankland District.

The party visited Nunijup Lake, on the Parson farm. It was described as:

“A magnificent stretch of fresh water… The lake, which is 16 feet in the deepest portion, contains clear fresh water and harbours a large quantity of English carp fish.”

The lake remained mainly fresh for some time and was used for drinking water and irrigation well into the 1960s.

By the 1970s the water quality had deteriorated and it could only be used for watering stock. In December 2018, measurements found a salinity level of 10 parts per thousand (ppt), which is ‘brackish’, and this jumped to a ‘saline’ reading of 22 ppt by late February. Seawater is around 35 ppt.

Under the surface

Though saltier than 100 years ago, the tolerance levels of various aquatic plant and macroinvertebrate species means that Lake Nunijup is still a thriving aquatic environment. The water clarity is good and healthy meadows of aquatic vegetation include Swan Grass (Ruppia spp.) and Foxtail Stonewort (Lamprothamnium sp). These play an important role in maintaining water quality and providing a food source for birds and other animals.

An interesting species is the aquatic Pond Moth caterpillar (Hygraula nitens) which feeds on the Ruppia. This underwater caterpillar (larvae) also makes a protective covering for itself using lengths of Ruppia stems and leaves held together with silk.

Macroinvertebrates are a crucial part of the lake ecosystem. They function as detritus decomposers, grazers and predators, and provide another food source for birds.

Seed Shrimp (Ostracod sp)

Image: Landcare Research NZ

Seventeen species of macroinvertebrates were collected from the lake in the summer of 2018-2019. Three species of damselfly larvae were dominant, along with the salt-loving seed shrimps (ostracods), which may have been carried to the lake in the feathers of waterbirds.

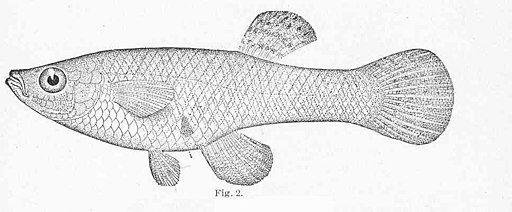

The hardy mosquito fish (Gambusia holbrookii) has been introduced into the lake, possibly by juveniles being transported on the feathers of ducks.

The presence of this fish likely accounts for the cormorants and high numbers of Musk Ducks found on the lake.

However, they reproduce abundantly and their presence is likely to have lowered the frog population, and ensured any small native fish cannot survive in the lake. Unfortunately, they are also not very effective in controlling mosquitos.

Reconnecting landscape

Connected areas of bush and restored habitat are crucial in the broader landscape. Lake Nunijup is a key stepping stone for wildlife and part of the proposed habitat linkage between the Stirling Range and the wetter forests of the Walpole Wilderness Area, being established as part of the Gondwana Link ecological restoration program. To the north and north-west of Lake Nunijup is a stretch of intact vegetation that is important habitat for animals like black gloved and tammar wallabies.

The catchment of the Kent River, which includes Lake Nunijup, was the focus of State Government attempts to reduce salinity in the catchment and river for many years. While clearing controls remain in place, the incentive program is long finished and funding has been much harder to come by for important on-ground works, like fencing-off remnant vegetation and replanting strategic areas.

The two organisations that work extensively in this area – Gillamii Centre and Green Skills – are eager to do much more ecological restoration work with the many landholders that surround the lake and farm in the catchment.

See & Do

Birdlife

Lake Nunijup is very important habitat for waterbirds and shorebirds.

Some of the waterbirds you might see include:

Plantlife

The remnants of dead trees scattered around the edge of the wetland are a clear sign that not all species can cope with increased salinity or the inundation from rising water levels.

The species that remain are more salt tolerant like the thriving Salt Paperbark (Melaleuca cuticularis) and the sedge (Baumea juncea).

Away from the edge of the lake are more woodland species, like the beautiful Eucalyptus wandoo.

Wandoo

(Eucalyptus wandoo)

Image: Nicole Hodgson

Wandoo has been called ‘nature’s boarding house’ because it is home to so many different animals and insects, including Carnabys’ cockatoos and the enigmatic phascogale.

Wandoo woodland was once widespread throughout south-western Australia, but has been mostly cleared.

Salt paperbark

(Melaleuca cuticularis)

Image: Katanning Landcare

Melaleucas can flower profusely with nectar laden flowers. Noongar people made good use of this nectar, straight from the flower or soaked in water to make a sweet drink.

The paper-like bark of mature melaleucas was also used in a range of ways when pulled off in large sheets – as a clean surface for food, as containers, or used in making shelters.

Sedge

(Baumea juncea)

Image: APACE

Rushes and sedges play a vital role in wetland health – their shallow roots bind the soil and reduce erosion, they slow water flow into wetlands, capturing nutrients and the roots help to oxygenate the water.

These were useful plants for Noongar people too – the roots were a source of food, they were used as fibre for weaving, and a stand of sedge and rush was always a sign that water could be found.

Walks

There are no formal walk trails at Lake Nuniijup but the open wandoo woodland that surrounds the lake is easy to walk through. It is also possible to walk around part of the lake that is fringed by Shire Reserve.

Day use area

There are toilet and firepits here, with overnight camping allowed. Another campground is at nearby Lake Poorrarecup.

- Pets are not allowed.

- Fires are prohibited all year.

- The lake is utilised for water skiing and swimming when water levels are high enough.

Giving back and getting involved

Two community-based organisations play an important role in protecting and restoring wetlands and other important areas in this area.

The Gillamii Centre is the long standing landcare group based in Cranbrook and working with the farming community and others on a wide range of sustainable practices.

Green Skills is based in Denmark and is a leading group in achieving the Forest to Stirlings section of the Gondwana Link.

Contact them directly to donate to their wonderful work or to get involved in citizen science investigations or ecological restoration activities.

Nearby

There are many other sites to visit nearby including:

Balijup Farm and Fauna Sanctuary

Balijup Farm has been farmed by the Hordacre family since 1923.

Twonkup

Known to the Noongar community as Dwangup, this is a very significant cultural site and a registered Aboriginal heritage site.

Warrenup Reserve and Kenny's Tank

Within a beautiful stand of mature wandoo woodland is the Warrenup wetland, within the Warrenup Reserve. Kenny’s Tank is an old well next to the wetland that is just a short walk off the road.

Lake Poorrarecup

Lakes, wetlands and rivers are a window into the health of the broader landscape, and Lake Poorrarecup is no exception, it has seen many changes in fortune over the past century.

Cranbrook Wildflower Walk

Take this 1.7km walk through predominantly wandoo woodland in spring and be rewarded by many beautiful flowers and a number of spectacular orchids.

Sukey Hill lookout

From Sukey Hill you’ll find a spectacular view of the western end of Koi-Kyeunu-ruff (or the Stirling Ranges). But the hill itself is actually a remnant of the original, ancient mountain range.

Practical Information

Directions

Lake Nunijup is 26 km to the south-west of Cranbrook via the Yeriminup Rd and Koonje Rd.

It is 33km to the south-east of Frankland River via the Frankland-Cranbrook Rd and Stockyard Rd.

Facilities

There is a small community hall at the lake, with nearby toilets, but no potable water available.

There are picnic areas and fireplaces, but no gas barbecues.

Pets are not allowed at the lake sites.

Camping is allowed at Lake Nunijup.

Please take your rubbish with you.

When to go

Winter and spring are recommended – when water levels will be the highest and the most plants flowering.

Closest towns

Cranbrook – 26km via Frankland-Cranbrook Rd

Frankland River – 33km via Frankland-Cranbrook Rd

Where to eat and stay

See the suggestions from our friends at Great Southern Treasures:

Visitor Information

Shire of Cranbrook

19 Gathorne Street

(08) 9826 1008

www.cranbrook.wa.gov.au

Frankland River CRC

(08) 9855 2310